Cross talk: a halfway point, a sidebar reflection

Annie Jael Kwan

In collaboration with Ada Hao, Trâm Nguyễn, Cường Phạm, Jia Qi Quek, Sau Bin Yap and Howl Yuan

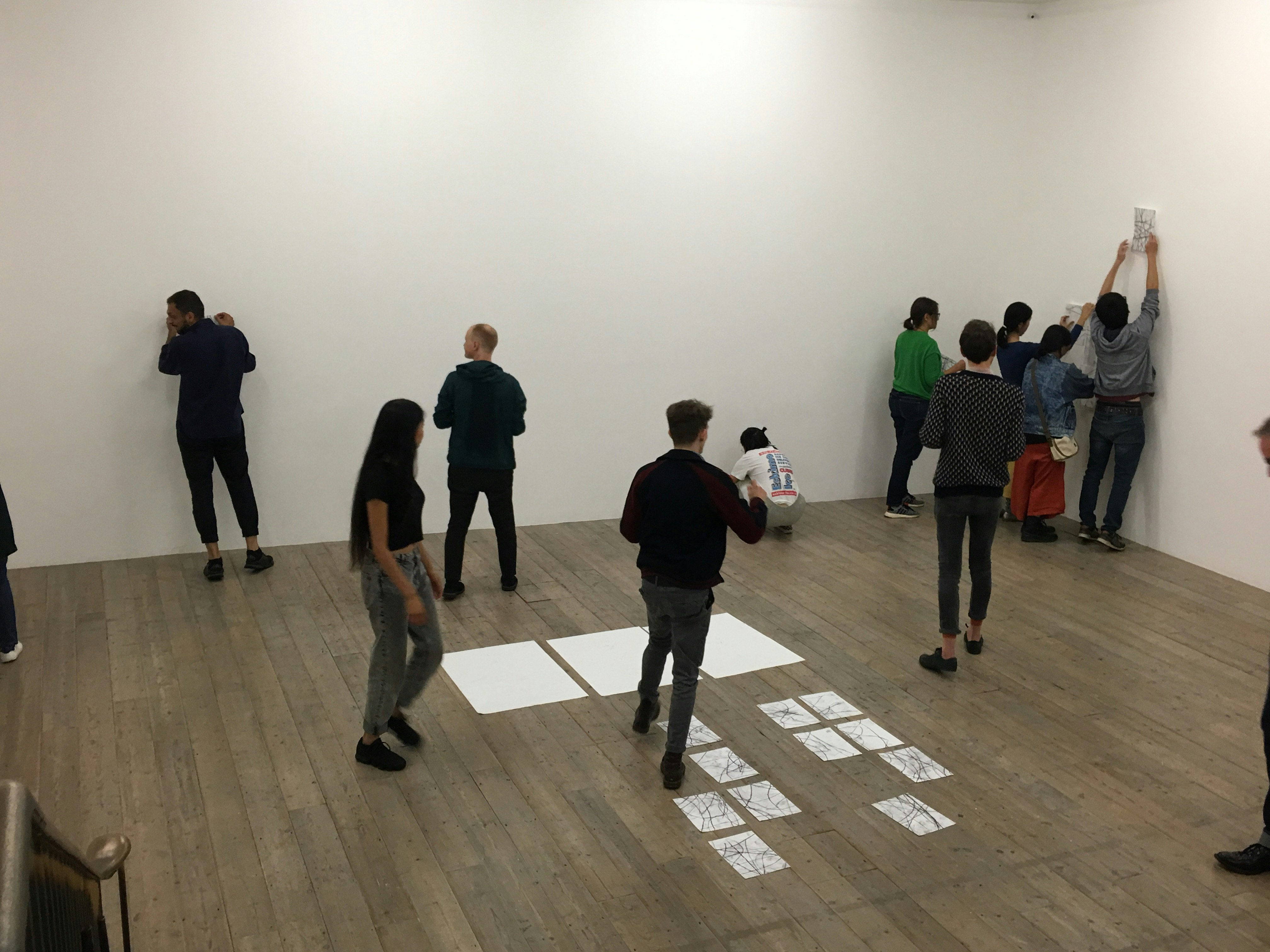

Asia-Art-Activism workshop: A collective timeline of Asian diasporic art and activism in the U.K.; photo: @alikati, courtesy the artists.

Asia-Art-Activism (AAA) was initiated in May 2018, first as an interdisciplinary and intergenerational online network of artists, curators and academics engaging with the question of ‘Asia’, ‘art’ and ‘activism’ in the UK via research and practice. Its principle aim was to complicate the conversations around the notion of ‘Asia’, including its problematic usage in different contexts of diasporas, migrant and resident communities, and its contested positioning in relation to cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s definition of ‘Black’ as a politically contingent grouping. A longer term mission of AAA is to examine the intersections and proximities of diasporic art and activism.

From July 2018, AAA was selected as one of a dozen groups to receive a twelve-month residency at the established art exhibition venue, Raven Row, situated in London’s Spitalfields. The residency provided a rent-free studio space and access to communal facilities such as meeting rooms and an event space. A central London location offered opportunities for programming a series of public talks, performances and screenings that continued to explore the paradigm of ‘Asia/Asian’ in an expansive way; having a studio meant AAA could create its own everyday co-working space, with a shared library of relevant archival materials, catalogues and books. This provision of space thus permitted a period of experimenting with models of working and ways of being together, asking questions such as: Is there truly a space that is outside and alternative to the exhibition? Can working modes continually remain open and mutable without resulting into chaos? How can relationships be centred in methods of research and public engagement? What else will emerge if we struggle to maintain openness and be not afraid to fail?

Halfway into this one-year experiment, some AAA members take the opportunity to discuss their shared experiences of the first six-months’ of forming, implementing and testing out how or what the network could work or be. Each contributor has engaged differently with the network—Ada Hao and Cường Phạm have undertaken short research residencies last fall within AAA; Trâm Nguyễn and Sau Bin Yap have contributed to public presentations and dialogues; Jia Qi Quek and Howl Yuan have just begun their Research Residencies in the new year. All are or were at some point associates of AAA, contributing to an ongoing discussion about what AAA could be.

Expressing the experimental and collaborative dynamic of Asia-Art-Activism, Cross Talk is a collectively written exchange that reflects on the unique opportunities and challenges that have emerged, based on discussions during associate meetings and other more informal chats. While ‘crosstalk’ is a technical term in the field of electronics that refers to unwanted signals caused by transference of energy that infiltrate a communication channel that does not relate to the main circuit of channel, here this sidebar discussion offers multiple perspectives of the discursive and critical considerations into the inner workings of an experimental, alternative space, and the insights shared regarding the difficult sustainability of a more open and equitable arts ecology.

— Annie Jael Kwan

Housewarming Pot Luck, 28 June 2018; photo: @alikati.

On beginnings: Why did you decide to join Asia-Art-Activism? What was the strongest draw? In what way did you imagine it would be beneficial or productive?

Annie Jael Kwan: I had previously worked within an experimental initiative called Something Human that worked with different curatorial collaborations. Our success in receiving public funding led to the organisation’s formalisation as a limited company that in turn brought other administrative obligations. As this process was undertaken, the question of what it meant to resist the urge towards institutionalising and all its encumbrances troubled me. I was attracted to an experimental project that would commit to struggling to remain open and collaborative for a year, and test what difficulties might exist, even at the risk of failure. In the beginning, I simply called upon my arts contacts working in relation to ‘Asia’ in someway and asked if they were interested in coming on board a research network via a website I set up. This coincided with a conversation that led to collaborating with producer and community organiser Joon Lynn Goh who was interested in diaspora and migrant activism. When our application to Raven Row was successful, it provided the unexpected catalyst of space—once you have space, you can start thinking about bodies-in-space.

Ada Hao: Annie asked me in an email if I’d like to join a virtual network of ‘a cohort of curators, artists and academics who are researching Asian art, archives, and activism.’ At the very beginning, without knowing what AAA was or what ‘it’ could be or become, I was drawn by curiosity to discover others who had signed up for this virtual network, and to consider the specific socio-political focus for the bodies of practice and research that formed around it. As an artist and an early-career researcher, I wondered if AAA could become a futuristic space and create new social relations for people who desire to define their experience as people of Asian descent.

Cường Phạm: Joining AAA allows us—researchers, artists, curators and activists alike—to be able to have a space to discuss, share and cultivate ideas relating to our respective fields. It also allows us a space outside of the mainstream to carve out our own narratives, the mainstream here [in London] being outside of the big institutions, academia and public spaces, but also places in Asia and North America where these conversations seem to be taking dominance.

Jia Qi Quek: I have always been thinking about the intersection between art and activism and I was interested in the openness to this network for care and confrontation. For me, AAA is a place to welcome collaborative, interdisciplinary and intergenerational collaboration that can unite different skill sets, histories, approaches for new ways to encounter and produce knowledge.

Trâm Nguyễn: It was something I was missing that I didn’t know I was missing. In my day job there would be times where I would be frustrated when brainstorming ideas with my specific framework of Asia, or postcoloniality, or diasporic positions, in relation to other ideas and concepts and it was hard for my friends and colleagues to contribute to this critically. I really felt AAA could be a space for this form of criticality I was craving.

Sau Bin Yap: My stay in London was short as I only had a one-year visa, and my initial idea was to visit more exhibitions and attend talks. When I was invited to join the initial formation of AAA, I found it interesting to be able to meet artists, researchers, scholars and curators with a background that is connected to or from Asia, but who are also based in London. AAA’s invitation provided a glimpse of another art ecology and an insight into the challenges such colleagues experienced, whether someone born in the U.K., or had migrated here. It was also interesting to think about why it had taken so long, or that it required the availability of Raven Row as a residency space to bring together the collective interest to contribute to the AAA platform/network, which is not embedded in a sense of ethno-cultural affinity but a shared geo-politico-cultural-epistemological outlook. And certainly, this pushed the constraints and limitations of ‘Asian-ness’. With this, also came a sense of the collegial which piqued my continued interest in AAA.

Howl Yuan: I joined Asia-Art-Activism at a point where I was looking for somewhere I could recognise and belong to in London. I commute between London and Bristol (where I am based) quite often, and find that London is such a big city that lives parallel other lives—sometimes we do nothing more than coexist. I decided to join AAA because it’s a platform that brings people together. I appreciate the term Asia-Art-Activism; it signals an ambition to look at those three areas in depth practically and collectively and within which I hoped I would be able to position my practice and myself.

What has been a meaningful experience in AAA?

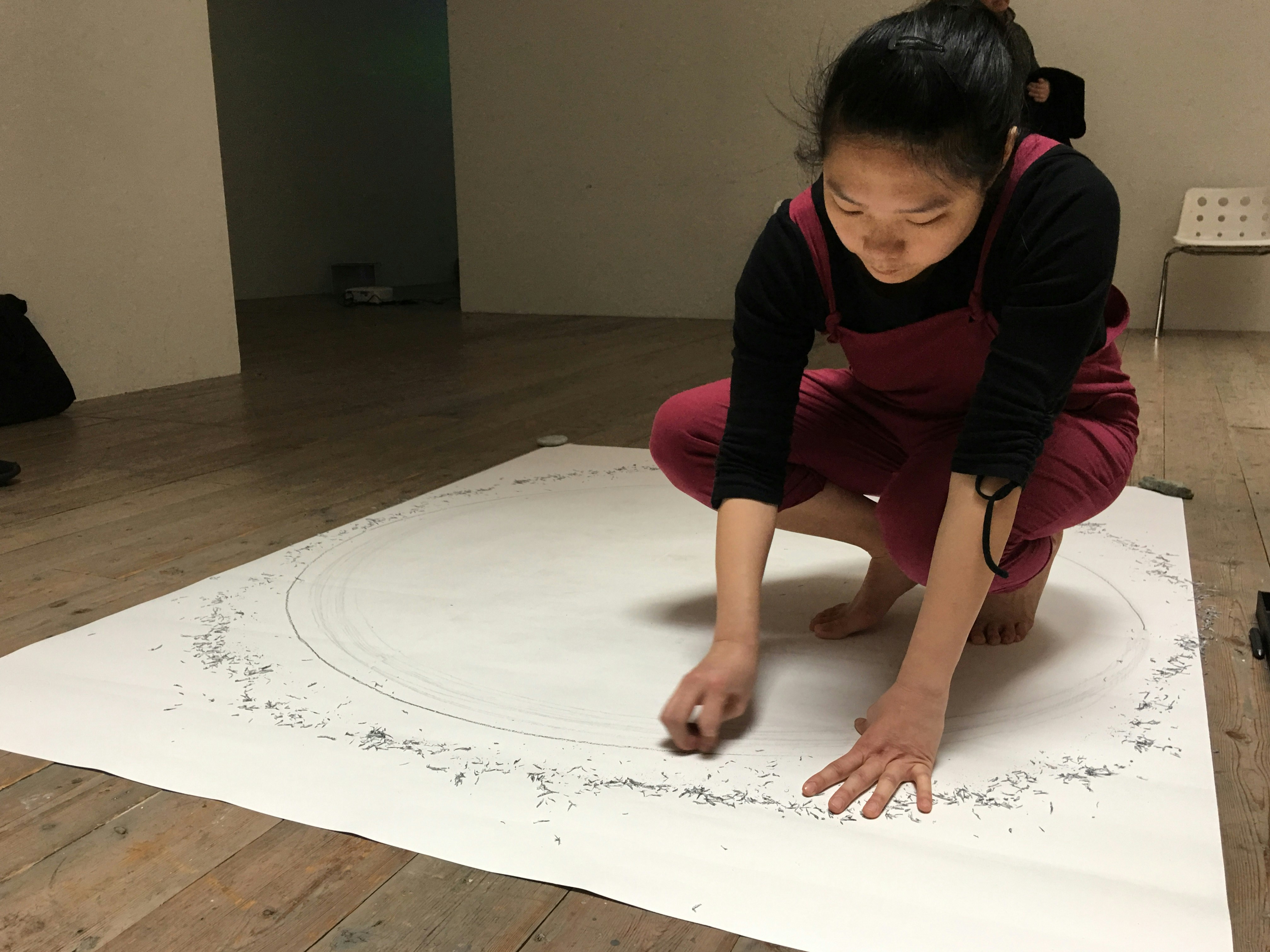

Ada Hao: During my residency at AAA with artist Bettina Fung, we curated a live art event with fourteen contemporary performance artists and two participatory projects happening simultaneously in the gallery space of Raven Row. I took the title of the event from Kathy O’Dell’s book on performance art: Contract with the Skin. The event happened as part of the three-day series of events, performances, talks and screenings at AAA. Accumulated actions took place in the eyes of public beholders, with the bodies from a shared Asian descent negotiating a contract of decoloniality and solidarity. Because of the presence of AAA and our physical studio space, I had an ‘excuse’ to invite people over for a chat and to introduce people of similar interests to share food, drinks and words together during London’s summer. And I found that we were all asking a the same questions: what would it be like to work together? Is there an urgent desire of performance artists to define their experiences as artists of Asian descent?

Jia Qi Quek: A highlight for me would be developing and leading events at AAA together with practitioners from different fields. For example, a recent collaborative food and reflection event, Oceans*A*Part, and some participatory workshops I will lead during my residency from March to April 2019. I appreciated being able to learn different means of production, modes of exchange and consumption via a social encounter. These exchanges allowed for the space to raise awareness and analyse the interweaving of specific narratives of each geopolitical context in the framework of a complex global discourse. Even something as simple as being able to unpack terminologies and concepts surrounding diasporic identities is what I would consider crucial in helping us understand and articulate our own situated knowledge. Integral to this process will be the binding together of multiple threads of lived stories to collectively confront our futures.

Cường Phạm: I think Flow [three-days of events, performances, talks and screenings held over 4–6 October 2018] is a particular peak for AAA. It was put together incredibly quick, there were many participants, but also the number of AAA members who contributed, volunteered, and attended. Its reach to the public impressed me too, it was humbling to see so many attendees.

I also enjoyed the events revolved around stuffing my face with food! Who knew something quintessentially Asian, the democratic hotpot, can cause so much controversy amongst the different Asian demographics. Myself and my wife brought pineapple, which caused quite a few hotpotees to raise their eyebrows, when at the same time, people brought turkey testes, peanut butter dip, durian mochi and unholy amounts of spiciness to the table—it was so much fun. Saying that, there has not been a AAA event I felt that has not been enjoyable; I always go away having learnt something new, having met interesting people, or had fun.

Howl Yuan: I have had lots of meaningful moments with AAA, but looking back I would say Flow stands out. Flow was the first time I brought my practice to AAA; it was also the first time I could see and experience many members’ practices. The experience helped me to comprehend each members’ practice, which also gives me a picture of what AAA is now and what AAA may able to be in the future.

Trâm Nguyễn: For me, it’s less about any specific event or moment or person, but the knowledge of having a network—it’s like having a net of people having your back, lol. But like a critical form of solidarity, people who would call me out, would help me think better, deeper, with more care. I feel like it’s a very generous space in that way, but like any collective space I don’t assume it is this way for everyone, but it feels like that for me. Even when I’m busy and can’t participate as much due to scheduling limitations, I still feel like knowing AAA is there is good enough.

Annie Jael Kwan: This is a difficult question for me as I’ve been so involved all the way through. The simple answer is that the existence of AAA as entanglements is meaningful—making space to be able to ask questions via practice is meaningful. The last six-months have provided many ups and downs, many moments of solidarity and success, and others where I’ve been pushed towards my limits of what is sustainable in the long run. I’ve seen generous actions of community and support, as well as self-interest and lack of commitment. But I’m accepting the process for what it is, and have been actively resisting early calls for thinking about definition and legacy. I’m enjoying holding onto the moment of ‘questioning’ instead of the usual struggle to already be something.

Who knew something quintessentially Asian, the democratic hotpot, can cause so much controversy amongst the different Asian demographics.

What has kept you returning to AAA over the last six months? What does AAA provide that you do not find in your other spaces of work, study or interaction?

Annie Jael Kwan: My response here is, at first, pragmatic—I’ve a responsibility to finish the project year as set out. But otherwise, I come to AAA repeatedly to be surprised and to learn. As an independent curator and researcher, I have mostly worked on my own or in very small teams, whereas at AAA I’m always humbled by how much knowledge there is out there, and how co-learning activates collaboration. I have been recently re-energised by a new project initiated with Joon Lynn Goh that seeks to collective map a timeline for diaspora/Asian art and activism in the UK.

Cường Phạm: My own research and community work is Vietnam/Vietnamese/Chinese-Vietnamese-diaspora-centric. Being a part of AAA allows me to move away from that and see what other individuals engaging in a similar practice are doing, enabling me to gain a broader perspective.

Sometimes the work I do is isolating, and by being apart of AAA I am constantly meeting new people which consistently freshens, challenges or add layers to my ideas and research. Because of the number of people who are part of AAA, and the people who attend our events, there is never a dull conversation. There was one particular instance that stood out, during a sharing session led by myself and Carô Gervay I was talking about an British-Asian post-punk/political rock band called Unit, that sprouted out of the Hackney Chinese Youth Centre, I came across them on the off-chance, when I spotted a couple of CDs in the storage room of Hackney Chinese Community Services, a local community group I’ve been working with.

One particular Unit song, War Crime, which is nine-minutes long, starts out with an a cappella disclaiming:

In 1961, President John F Kennedy was clearly most concerned

that the far eastern communist tide had finally turned,

so he sent B52s and all the G.I.s he could use

to torture, rape and kill, according to their will,

until 30,000 South Vietnamese corpses burned.

Is it too much to ask that one day this lesson will be learned?

Then the voice of a young Kim Phúc fades in, who is most well-known as the napalm girl in the picture taken by the photographer Nick Út, talking about that famous picture and the effect the war has had on her body, family and country. The chorus goes: Giải phóng, there’s a victory in Vietnam / Giải phóng, there’s the death of Uncle Sam. The word ‘Giải phóng’ or 解放 in Hanzi, or Hán Việt (a writing system Vietnam no longer uses) means liberation and is pronounced by Unit’s vocalist with a hard ‘g’ rather than the ‘z’ which is the standard Northern Vietnamese accent.

At first I thought the ‘error’ it was simply an indication of the level of the Vietnamese language abilities of members of the band. However, it was only later when Bettina Fung, another AAA member, approached me after the formal part of the sharing session was over that we came to realise it was gaai2fong3, the Cantonese pronunciation. The song is clearly about the Second Indochina War, yet the pronunciation anchors it differently. Instead of viewing this band singing ‘inauthentically’ (as problematic as that sounds) about a Vietnamese experience, this band is a convergence of overlapping Asian and British influences, cultures, and languages.

Ada Hao: I think of AAA as a performative space and also a home-like space because whenever I come to AAA, either to work during my residency or to drop off something for someone or to help with a public sharing event, I always feel that I’m engaged in trying on roles and relationships of belonging and foreignness.

Howl Yuan: My practice focuses on the mobility of humans and objects, using this as a method to approach an idea of cultural mobility. Both forms of mobility are supported and cared for within AAA. This doesn’t mean that I gain little support from my school or other artist collectives I am involved with, just that the sense of solidarity at AAA really keep me here.

Jia Qi Quek: A genuine interest in growing our own research practice, but more so, being able to share and exchange with intersectional creatives. AAA brings together a growing community of practitioners and acknowledges each of our own expertise to support one another. I think we, or at least practitioners who are in the expanded field of post-studio practice today, are looking for more substantial participation and the possibility to enact change.

Trâm Nguyễn: A sense of friendship and solidarity, really. Even though a lot of us come from different backgrounds—culturally, career-wise, or even levels of commitments to the group—it still feels like a more level playing field when it comes to discussion, where everyone can learn from each other. To me. it tends to not have a sense of tokenism or burden of representation that a lot of spaces I inhabit have and therefore frees that part of my brain up to think differently.

Chả giò conversations; 16 December 2018; photo: Jalaikon.

While AAA started with a core group of ‘leaders’ that were driving things forward, slowly, it tried to find ways of allowing more participation in leadership and giving voice. How have you found this process? What was your role in AAA?

Annie Jael Kwan: The role of being a core member has been challenging. There was so much unseen work behind the scenes and emotional labour. It took up much more time and energy than we anticipated, and additionally, I’ve had to hold the safety net knowing I’m responsible and liable, and also, when push comes to shove, I’ve felt a strong obligation to show up for the members as much as I can. But this position is shifting recently as I’m learning my limits, and at the times when I’ve hit those limits I have to activate my right to conserve and preserve. By doing so, I will also make space for those who can step up.

Cường Phạm: There are many ways for AAA associates, but also non-associates to get involved. Over the period I have been involved I have seen people come and go, and that all depends on the time you are willing to invest. We have many events and also monthly meetings which allows us to contribute and participate in the process. When friends ask me how did I get involved in AAA, I always tell them to come along to the events, meet the other associates, and in time this will lead to greater involvement.

Ada Hao: I feel AAA is like a piece of dough and could be turned into more than a single piece of its manifestation, either with a few pairs of hands or many. I feel more responsible to play the role of a host at AAA, especially when I was doing my residency at Raven Row. I think our collective leadership at AAA is a process that motivates self-management and self-care. It requires us to be cohorts, like co-editors for this piece of text, so to shape AAA on an inclusive common ground.

Jia Qi Quek: My involvement with AAA includes being a participant, research associate and artist-in-residence. Despite being uncertain of ways I could contribute initially, I have always found AAA a curious and supportive platform to collectively develop ideas. I believe that collaboration should always happen organically and over time AAA has created an environment of trust for me to propose ideas, events and to question. AAA is a labour of love, commitment and dedication: You get what you put in. You learn from committing to the work.

Howl Yuan: I haven’t been involved in AAA as much as I feel I should because my residency at AAA only begun in April 2019; also, I’m not based in London like the other members. In general, I feel that everyone’s voice is heard and of value. Unlike an established art venue or organisation, I find AAA more accessible. Some might argue that AAA moves or acts rather slowly, but at least we move forward as a collective, and that’s important to me.

Trâm Nguyễn: I have never been part of a collective before, so I was curious/interested/a little bit scared to be honest because I know myself to be terrible in group dynamics. But from my perspective, everyone has been generous enough to balance individual goals and the collective goal of AAA—although I’m not 100% sure what that is yet. I acknowledge I have not been able to take on a lot of the administrative work that other members have done, but I can’t over-promise. And we’re all working on this out of passion and alongside things that pay the bills, so it’s everyone’s good will that keeps making things happen. There were multiple attempts to shift the working practice and move towards a collective accountability and shared responsibility model, but even coming up with this ‘system’ takes work, which often can be invisible.

SEA Currents: what gets stuck in the eddy goes around and around. Bettina Fung, Towards All & Nothing, 8 March 2019; photo: @alikati.

What have you found challenging about AAA? What would you change if you could?

Jia Qi Quek: As with all kind of collective work, it is non-profit, driven by genuine interest and purpose for collectivity. While I appreciate AAA’s collaborative ethos, a challenge could be the balancing of physical and psychological labour to put into care, service and humility at the centre of what we do. This could dangerously and potentially allow practitioners to feel that they are open to self-exploitation, driven by invisible pressure and blurred division of responsibility. Moving forward, perhaps having some system to rotate administration roles, and some degree of structure would be helpful. Nevertheless, it is wonderful that we have the capacity and transparency to conduct open meetings to discuss the complexity and contradictions of these internal processes at AAA. After all, AAA unfolded with a more long-term intention to nurture a collective spirit, and there is a value in being able to explore artistically without the pressure of overcomes—we do do that and that’s the beauty of AAA!

Cường Phạm: Because AAA is a large collective it can mean it does take a while for things to get going. It also means we don’t all have independent access to Raven Row. The Researcher-in-Residence evolved as a means to give everyone an opportunity to have a space to work in. I tend to see challenges as a way to think and do creatively, rather than seeing it as a blocker.

Annie Jael Kwan: I think one of the challenges is getting everyone on the same page as to how words are used to define AAA—is it a network or a collective? What is the difference between working collaboratively, and having a collective spirit, and being a collective? For me, there are subtle differences, but with consequences, so I think it’s important to be keep asking these questions and pushing the boundaries of what is feasible in terms of material resources, time and individual commitment. I’ve also accepted that there will be needs that AAA cannot meet—those are its limitations too.

Trâm Nguyễn: It’s not AAA itself that I find challenging, but finding the time do this alongside a full-time job, the right way, with care to the work and to everyone. I wish I could actually balance things better and find more time to do the research and projects I’m interested in with other AAA members and make the most of the knowledge and experiences already around. But as I say this I think, ‘Great, more administration and structures!’

Ada Hao: Considering the mutable characteristic of AAA, would it be possible to let go of our hands on the bicycle? What would it be like if we manifest the urgency of our action, without the think of what AAA would be like in the future?

SEA Currents: Tram Nguyen in conversation with Sung Tieu, 10 March 2019; photo: @alikati.

How do you see AAA evolving? Is a physical space important? How can AAA continue to play a role after Raven Row?

Jia Qi Quek: I see AAA evolving as a collective that can be a model that extends each individual’s capability, generates critical awareness and visibility for something that previously has not existed in this form. Activism is not always spontaneous—it can be both meticulously mapped out and staged, or with lots of trial and error, but either inevitably brings risk. We are still articulating new languages to communicate from our own positions, be it through experimenting with different ways of self-organising or collective performances. From conversations generated from public events or personal encounters, there seems to be a philosophical and ethical dissatisfaction with predominant discourses and an urgency to have a safe space to address some of the concerns and issues surrounding ‘Asia’, how it is perceived and pursued in certain spaces. These growing tensions and concerns are a consolidation of familiar exclusionary discourses around forms of ethnicity and identity that should no longer be a private conversation.

Trâm Nguyễn: Funny you should ask as I haven’t really even mentioned the physical space up until this point. That’s not to say that it isn’t important, because a lot of spaces are unsafe for us physically and conceptually so there is a need for us to have a space in order to foster these conversations, but it can literally be anywhere.

Cường Phạm: The physical space has been important to AAA thus far and so it will be interesting to see how AAA will continue outside of Raven Row. The centrality of Raven Row, in the art world but also within London’s geography, makes it an important meeting place. While these conversations can be held anywhere, it makes it a lot easier having a physical space to do so.

Ada Hao: The physical space is important for AAA so far. However, I wonder if the physical space for AAA could be nomadic? There might be opportunities to realise ideas we haven’t been able to due to the limited usage of the public space at Raven Row. Metaphorically, AAA is like a ship that is navigated by us sailors to anywhere with the surfaces of water and currents.

Howl Yuan: Yes, physical space is essential to maintain and develop the collective. Although virtual space like Facebook and WhatsApp is helpful to continue our conversation, they have their limitations. As long as our community is there, we can always find somewhere.

Sau Bin Yap: AAA@RR is an incubator, a place of convergence. And perhaps divergence too when conflict, disagreement and differences arise from discussion and processes of working together, which i think is normal, and part and parcel of integrating multiple interests and understandings of working-together (and I don’t mean ‘collectivism’ here). I always thought that space is politics, in the sense of a physical space as a medium providing a congregation of people. It certainly involves issues of resources, distribution, management and providing access to material manifestations of event, exhibitions and projecting a certain artistic/intellectual outlook. But when the physical space dissolves, AAA as a platform would rely more on its strength as a network of actors, a node whereby dynamics flow and are played out accordingly.

Annie Jael Kwan: Where there is convergence and divergence there is the contingent. It’s not always bad, either. There are urgencies that bring people together and that point of meeting can be a crucible for cultivatig new collaborations, germinating new ideas and so on. Then the long view is that things must change and other push-pull factors may lead to separation or changing dynamics. For me, the biggest driver is how we can share knowledge and how knowledge can be distributed—and thus, how can power structures be re-imagined and reconfigured.

Asia-Art-Activism studio at Raven Row, 18 September 2018; photo: @alikati.

About the contributor

Annie Jael Kwan is an independent curator and researcher.