Talking and not talking about race: curating Asian-Australian identities in the early years of 4A

Tian Zhang

Inaugural exhibition at Gallery 4A, Sydney, 1997 (installation view). Clockwise from left: Emil Goh, The Bride (The Last Nonya), 1996, type C print, courtesy the artist; Emil Goh, The Wedding (The Last Nonya), 1996, type C print, courtesy the artist; Lindy Lee, Birds of Appetite, 1996, wax and synthetic polymer paint on board; courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; photo: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art archive.

There was no theoretical conversation about Asian-Australian identity … there was very little framework from which to conduct a conversation.

— Melissa Chiu (1)

The formative years of 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (4A) were opportunities to experiment with different strategies of supporting Asian-Australian artists through the process of exhibition-making. Founded by a group of Asian-Australian artists and their supporters in 1996, the Asian Australian Artists’ Association (AAAA) and its first gallery space, known as Gallery 4A, was located on the third floor at 405–411 Sussex Street in Sydney’s Chinatown district of Haymarket (2). Spurred by the lack of engagement with and representation of Asian-Australian artists by Australian institutions, the group had come together with the aim to ‘foster and encourage the professional development of Asian-Australian artists’ (3).

As signalled by 4A’s first curator and director Melissa Chiu’s opening quote to this essay, there were few blueprints available for how this could be done. In Australia, there was little discourse around Asian-Australian identity, with groups like the Asian Australian Studies Research Network (AASRN), which has been instrumental in developing theory around Asian-Australian and diasporic identity, yet to be established until 1999. While inspiration could be drawn further afield, with exhibitions such as The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s (1990) and the 1993 Whitney Biennial beginning to explore race politics in the United States through inclusion of African-American, Asian-American and other ‘hyphenated’ identities, there were also limitations to the transferability of such methodologies to the specific context of Asians in Australia.

Filipino curator, art historian and critic Patrick Flores describes a type of ‘homegrown curator’, whereby a curator’s practice is formed ‘in response to everyday exigencies of getting things done, improvising here and there, but at the same time building bit by bit the necessary infrastructure needed for the system’ (4). The early years of 4A could be viewed within such an approach, where the absence of applicable frameworks meant that the gallery, through the directorship of Melissa Chiu and later, Binghui Huangfu, had to create their own responses to specific issues arising from the local context. It is instructive to look at 4A’s early exhibitions—the inaugural exhibition (1997), Bilingual: Six Translations (2000) and Asian Traffic (2004)—as a means of seeing how its curation and presentation attempted to counteract two of the major issues facing Asian-Australian artists at the time—the tendency to be excluded from exhibitions of ‘Australian’ art and the propensity for their works to be viewed in an exoticised, ‘Othering’ lens.

Inaugural exhibition at Gallery 4A, Sydney, 1997 (installation view). From left: Lindy Lee, Birds of Appetite, 1996, wax and synthetic polymer paint on board; courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney; Emil Goh, The Wedding (The Last Nonya), 1996, type C print, courtesy the artist; photo: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art archive; courtesy the artists.

When 4A first opened its doors in March 1997, the inaugural exhibition (untitled, 1997) was a group show featuring three Asian-Australian artists: Emil Goh, Lindy Lee and Hou Leong. Curated by Melissa Chiu, 4A’s first curator and later director, the exhibition hinted at the breadth and depth of Asian-Australian art. Goh’s The Last Nonya (1996) series included two images from his mother’s wedding, while Leong’s works, Autobiography: With Chairman Mao (1994) and An Australian: Cricket Hero (1994), applied the artist’s face onto appropriated photographs. In contrast to these photographic works, the exhibition also featured an abstract painting by Lee, Birds of Appetite (1996).

Reflecting on the exhibition now, Chiu remarks, ‘In very different ways the three artists presented different approaches to their own identities but also represented the multiplicity of what it meant to be an Asian-Australian’ (5). Indeed, each work reflected the artist in some way but through vastly different methodologies. Goh’s use of family photographs and the word ‘Nonya’ in the title could be seen as a personal reclamation of his culture and heritage (6). Leong’s photographs, on the other hand, inserted himself into fabricated scenarios, one distinctly Chinese and the other Australian. Meanwhile, Lee used paint symbolically to contemplate oppositions, such as the experience of different cultures (7). In addition to medium and subject matter, the exhibition also reflected the diversity of Asian-Australian artists. Lee, who was born in Australia, was a relatively established artist, while Goh was a recent arts graduate, who was born in Malaysia but had lived in Australia for more than a decade. Leong, on the other hand, was a relatively recent migrant from China.

In contrast to her appraisals now, however, Chiu’s statements at the time of the inaugural exhibition were markedly more restrained. When asked in a media interview about the curation of the show, she commented, ‘The first exhibition at Gallery 4A was intended as an introduction. Initially I was interested in these three artists because ideas of self-portraiture are latent themes for them.’ She added, ‘This combination of emerging artists and established artists is a policy which we would like to continue in the future’ (8). Chiu’s discussion of the exhibition can therefore be contextualised within what Flores terms search for the new, a curatorial gesture for ‘replenishing the inventory of contemporary art’ (9). The exhibition served as an ‘introduction’ to these Asian-Australian artists, two of whom were very emerging at the time.

What is notably absent from Chiu’s interview or indeed, any other material related to the exhibition, were explications of the cultural context of the works or the personal histories of the artists. Instead, in the same media interview, Chiu stated that the gallery was ‘not concerned with setting up the discourse of a minority culture’ (10). Chiu’s resistance to entering into such a discourse and her avoidance of talking about the artists’ cultural backgrounds during this interview might seem incongruous with the establishment of an Asian-Australian space.

In order to understand this strategy, it is important to consider how Asian-Australian artists were regarded at this point in Australian art history. Asian-Australian artists were often overlooked for opportunities such as the Asia-Pacific Triennial and Asialink, and excluded from showcases of Australian contemporary art, which tended to favour Anglo-Australian artists (11). When they were included in exhibitions, there was often an incommensurate emphasis placed on their ‘Asianness’. Art historian Michelle Antoinette notes:

[Anglo-Australians] become somehow divorced from ethnicity and their art is more commonly discussed in terms of other, more formalist, aesthetic concerns (i.e. art movement, style, composition, etc). This is rarely the case for Asian-Australian artists whose art was often interpreted primarily in terms of ethnicity and only then — although not always — in terms of formalist aesthetics (12).

This preoccupation with cultural origins can be contextualised within prominent Australian cultural studies professor Ien Ang’s reflections on the question, where are you from?—a query not unfamiliar to anyone living in diaspora. Ang posits that by focusing on cultural origins, that is, where one is from, the focus is taken away from their present location, or where they are at. Ang suggests that ‘so long as the question “where you’re from” prevails over “where you’re at” in dominant culture, the compulsion to explain, the inevitable positioning of yourself as a deviant vis-à-vis the normal, remains’ (13). Hence, by overly concentrating on the cultural origins of Asian-Australian artists (‘where they are from’) the focus is taken away from their contributions to Australia (‘where they are at’) thus, compounding their marginality.

Within the framework of 4A’s inaugural exhibition, it could be argued that in refraining from highlighting biographical and cultural information of the artists, Chiu was trying to circumvent tendencies to view Asian-Australian artists through a lens of exoticism and ‘Otherness’. Reflecting on another exhibition, the three-part Signs and Wonders (1998), that comprised individual exhibition presentations by Suzanne Victor, Juliana Wong, and Regina Walter, Chiu remarked:

at the heart of the curatorial project it was always, ‘Can we talk about race without talking about race?’ That was one of the ideas of that show. It was like, ‘Okay, we’re showing in an Asian-Australian mission-driven space but we’re just going to show art with no mention of that’ (14).

Regina Walter, Everyday Elegance (installation view), 1999; photo: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art archive, Gallery 4A, August 1999; courtesy the artists.

Can one talk about race without talking about race? It can be seen that Chiu’s tendency to focus on the non-cultural aspects of the works in the inaugural exhibition—for example, formal elements like self-portraiture rather than the cultural context of the works, and speaking to the artist’s stage of career rather than migration or cultural background—were attempts to diminish their marginality, and to describe and inscribe these works by Asian-Australian artists with the values usually assigned to Anglo-Australian ones.

Having outlined the possible reasons for such a strategy, however, the downplaying of cultural context could also be counter-productive, particularly for understanding personal works. For example, in the case of Goh’s photographs, the lack of contextualising information such as his Peranakan background meant they were read only through an aesthetic lens, bypassing the complex layers of diasporic subjectivity within the work. Rather than passing judgment on such a strategy, this observation is useful in foregrounding the types of dilemmas that 4A was grappling with at the time.

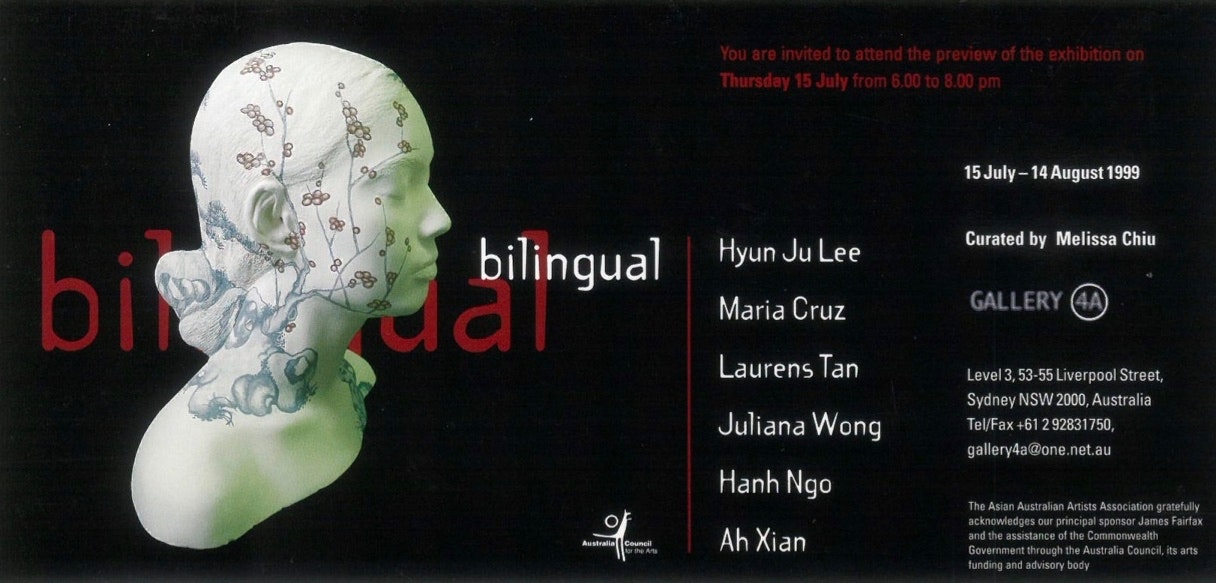

Invitation to Bilingual: Six Translations; photo: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art archive; Gallery 4A, July – August 1999; courtesy the artists.

Chiu’s later exhibitions, such as Bilingual: Six Translations (2000), contributed to understandings of Asian-Australian and diasporic subjectivity, the very type of ‘minority discourse’ she had once outwardly rejected. Featuring Ah Xian, Hyun Ju Lee, Maria Cruz, Laurens Tan, Juliana Wong and Hanh Ngo, the exhibition examined the concept of biculturalism through themes of bilingualism and translation. Some artists became implicated as cross-cultural translators who melded Asian and Western cultural symbols in their works. For example, Ah Xian’s series China, China (1998–2004) featured sculptural busts, an icon of European sculptural tradition, made from porcelain and inscribed with traditional Chinese decorative motifs (15). Hyun Ju Lee’s Power of the World (1998) paintings used Minwha (Korean folk painting) and pop art sensibilities to create tiger motifs on American dollars, symbols of economic and political power from different cultures. A different type of bilingualism was explored by Juliana Wong, who used an interactive computer program to investigate the role of technology as communication. Meanwhile, Maria Cruz, Hanh Ngo and Laurens Tan conceptualised translation through medium and materiality—Cruz appropriated suburban graffiti into paintings, Ngo transformed shards of Annamese ceramic plates into tapestry works, while Tan reconfigured car doors into sculptural juke boxes (16).

The diversity of the artworks, in terms of media and perspectives, was an important strategy to highlight the individuality of each artist’s expressions and to subvert any tendencies to essentialise their practices. In addition to diversity of form and style, Bilingual also showcased Asian-Australian artists from different cultural backgrounds, including Korean, Filipino and Vietnamese, to further break down stereotypes around ‘Asian Australianness’. This was a significant strategy as there was often a tendency to conflate Asian-Australian identity with Chinese-Australian identity (17). Hence, through the diverse representation of media, perspectives and ethnic background, Bilingual was able to represent the multiplicity of perspectives and positions that make up ‘Asian-Australian’.

Chiu writes in the catalogue:

[W]ork by Asian Australian artists has frequently been explained in terms of biographical or cultural influences. Although some Asian Australian artists draw directly upon their cultural heritage as a source for their work it is also true that there remains a number of artists for whom such a reading would be limiting…By presenting a range of work by artists whose backgrounds and art practices possess more differences than similarities, Bilingual aims to deconstruct prevailing assumptions that work by Asian Australian artists is necessarily a direct reflection of their cultural heritage (18).

This was the first time within an exhibitionary context that Chiu had vocalised such observations—that Asian-Australian artists were often limited by stereotypical cultural readings of their works (19). This newfound openness was perhaps bolstered by the consolidation of Asian-Australian discourse, with two major conferences on Asian-Australian identity being held the previous year (20). Chiu’s discussion of the artists in Bilingual touches on the concept of ‘strategic essentialism’ coined by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, whereby the evocation of identity is used strategically to re-invent and re-negotiate one’s position (21). Writing self-reflexively in relation to her Chinese diasporic identity, Ang explains:

[S]ometimes it is and sometimes it is not useful to stress our Chineseness, however defined…[P]ostmodern ethnicity can no longer be experienced as naturally based upon tradition and ancestry. Rather, it is experienced as a provisional and partial ‘identity’ which must be constantly (re)invented and (re)negotiated. In this context, diasporic identifications with a specific ethnicity (such as ‘Chineseness’) can best be seen as forms of ‘strategic essentialism’: ‘strategic’ in the sense of using the signifier ‘Chinese’ for the purpose of contesting and disrupting hegemonic majoritarian definitions of ‘where you’re at’ … In short, if I am inescapably Chinese by descent, I am only sometimes Chinese by consent… (22).

While previously, Chiu had been hesitant to engage in such a ‘minority discourse’, the curation of Bilingual shows the development of Chiu’s curatorial oeuvre to engage in these types of discussions of diasporic identity.

Foreground: Ken Yonetani, Fumie – Tetrapods, 2004, mixed media installation, courtesy the artist; background: Kijeong Song, Couples, 2004, C-type prints, courtesy the artist; photo: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art archive, Asian Traffic (Phase 3), 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2004; courtesy the artists..

While 4A’s early exhibitions throughout the period 1997–2003 were small group shows exploring facets of Asian-Australian identity, the organisation soon expanded this conversation to encompass the fluidities and complexities of Asian diasporic subjectivity more broadly. Following Chiu’s appointment as director of New York’s Asia Society Museum in 2004, Binghui Huangfu became director of 4A from 2003–2006 (23). An experienced curator, Huangfu had previously directed the Earl Lu Gallery in Singapore where she had curated large and progressive international exhibitions including the first major survey of contemporary Asian women’s art (24). Like Chiu, Huangfu was conscious of the issues of stereotyping and exoticism, commenting that Asian-Australian artists have to contend with the binary of ‘being seen either as a contemporary artist or as an Asian contemporary artist’ (25). However, while it could be said that Chiu’s curatorial strategies sought to counteract this by repositioning Asian-Australians within Australia, Huangfu’s projects aimed to promote better understanding of Asian-Australians by the wider public through increased engagement with Asian perspectives in general.

One of the best examples of this was Asian Traffic (2004), an ambitious multi-chapter exhibition involving six exhibition phases over four months that was developed as a parallel event to the 14th Biennale of Sydney. Featuring 15 local Asian-Australian and 15 international artists, most of whom were from Asia, the project showcased the ‘vibrancy and dynamic output that is contemporary Asian art today’ (26). The exhibition utilised the concept of traffic as the overarching framework — a metaphor for the movement of people as well as the migration and exchange of ideas.

The exhibition circulated around personal, social and political concerns, which emerged and re-emerged throughout the six phases. While some phases presented a coherent stream of ideas, others were more a ‘traffic jam’ of multiple considerations. Furthermore, the structure of the project allowed some works to be installed and left in the gallery across phases, which Huangfu hoped would create ‘a new dynamic between the works every time we change the relationships between them’ (27).

Phase 1 (4–19 June) reflected on issues of religion and culture: Mella Jaarsma’s absurdist wearable pieces critiqued cultural and religious clothing, while Shen Shaomin rearranged real bones to create fictitious animals, interrogating both religion and science. Questions around religion also resurfaced later in Shilpa Gupta’s installation, which presented 40 pieces of canvas blessed by 40 different holy persons from a range of religions. Broader political issues were presented in Phase 2 (22 June – 10 July): Vasan Sitthiket’s shadow puppets of famous figures such as Jesus Christ, Hitler and Saddam Hussein, were animated by the artist to create satirical commentary, while Jiang Jie occupied the street-front gallery with strollers to critique Western adoption of Asian children. Environmental concerns were discussed in Ken Yonetani’s work in Phase 3 (16—31 July), with 300 ceramic tiles of endangered butterflies installed on the floor of the gallery, which visitors were forced to trample on during opening night.

Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2001, process-based installation, video, 40 canvases, television, lights, carpet; photo: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art archive, Asian Traffic (Phase 3), 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2004; courtesy the artist.

Issues of identity and culture emerged in several phases of Asian Traffic. Kijeong Song navigated the ‘dissolution of cultural barriers’ through intimate photographs of cross-cultural couples in their homes (28). Owen Leong’s video Second Skin (2004) presented himself writhing against layers of honey on his skin as an attempt to ‘make visible the concealed socio-political structures that mark our bodies through race, gender and colour’ (29). Drawing on both Western mind- body-awareness techniques and East Asian breath awareness practices, George Poonkhin Khut’s interactive installation created sounds and visualisations based on participants’ breathing. In contrast, the later phases featured more aesthetic motivations. Sangeeta Sandrasegar’s sculptural work in the last phase (Phase 6, 16 September – 2 October) used paper cut-outs and light to produce haunting shadows on the gallery walls. The opening night also featured Peng You and Sun Yuan’s ephemeral installation of a cubic metre of dry ice, which melted and disappeared throughout the course of the night.

Sangeeta Sandrasegar, I’m Half Sick of Shadows, 2004, paper cut-out panels, glitter, glass beads; photo: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art archive, Asian Traffic (Phase 6), 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2004; courtesy the artist and Mori Gallery, Sydney.

Presenting a cacophony of media, techniques, style and concerns, Asian Traffic showcased the breadth of art being produced by artists of Asian descent, locally and internationally. Although some artists chose to explore concepts relevant to Asian or diasporic subjectivity, others examined non-cultural issues like the environment or more formal concerns. While this strategy had previously been used by Chiu to subvert stereotypes of Asian Australians, Huangfu used this methodology to de-essentialise concepts of Asians more generally. Furthermore, Asian Traffic utilised a form of strategic essentialism, whereby the word ‘Asian’ was used tactically to reclaim the term as a fluid and diverse concept, and to challenge and re-invigorate dominant perceptions of Asia.

Reflecting on Asian Traffic, Huangfu noted that one of the key aims was to present to ‘Australian audiences the diversity of what has been produced in Asia and show as a counterpoint the directions that have been taken by younger Asian-Australian artists’ (30). Unlike the inaugural exhibition and Bilingual, were Chiu had attempted to locate Asian-Australian artists within Australia, Huangfu’s Asian Traffic positioned Asian-Australian in relation to Asia. It could be argued that while Chiu’s curatorial positioning was guided by a focus on where one is at, that is, Australia, rather than where they are from, that is, Asia, Huangfu believed that a recognition of where one is from is necessary to inform where one is at. In this sense, Chiu’s curatorial strategies were framed within a multicultural discourse, where ideas of difference are situated in reference to a dominant (white) Australian culture. Huangfu, on the other hand, was vocally opposed to the multicultural agenda, which she considered restrictive and reductive, and which she argued ‘has at its base the containment of difference into the exotic or multicultural pockets’ (31). Furthermore, she stated, ‘At no point are we [at 4A] trying to place contemporary Asian art in a multicultural context, as we see this as being dangerously close to exploring the exotic’ (32). Huangfu’s statements echo Ien Ang’s wariness of multiculturalism, who argues:

not only [does multiculturalism] marginalise so-called ‘ethnic’ cultures, but also, damagingly, creates a situation in which white or ‘Anglo-Celtic’ Australians are encouraged to construct themselves as outside ‘multicultural Australia’ (33).

It could also be said that while Chiu was herself critical of binary constructions of ‘Australia’ and ‘Asia’, she nevertheless relied on a form of binary positioning to discuss Asian-Australian subjectivity. For example, the dilemma of where you are at versus where you are from presents a form of binary postulation, and moreover, exhibitions such as Bilingual referenced biculturalism as a duality. Huangfu’s conceptualisations of cultural identity, on the other hand, embraced more fluid notions based on ‘cross cultural dialogue and hybridisation’ (34). For example, Huangfu’s curatorial essay for Asian Traffic emphasised the variability and specificity of diasporic subjectivity, saying that it ‘affects cultural development in multiple ways based on place, time and the combination of cultures which are pushed together by the experience’ (35).

This multiplicity of perspectives and situations was also signified through the metaphor of ‘traffic’—conjuring notions of flow and stasis, as well as movement in a myriad of different directions. These were conveyed, not just in the content of the exhibition but the mobilisation of the exhibition’s structure, where some artworks came and left, while others remained over several phases. Asian Traffic could be seen to be the first exhibition at 4A to fully incorporate what American curator and writer Maura Reilly describes as a relational studies or ‘polylogue’ approach to curation, which rejects a ‘monologue of sameness’ in favour of a ‘multitude or cacophony of voices speaking simultaneously’ (36). Reilly argues that this curatorial strategy presents art ‘as if it were a polysemic site of contradictory positions and contested practices’, which ‘goes beyond a mere description of discrete regions and cultures’, ‘collapses the destructive centre-periphery binary,’ and is ‘essentially postmodern in nature’ (37). This amorphous, post-structuralist exhibition format reflected Huangfu’s fluid conceptions of identity and diaspora.

Both Chiu and Huangfu were pioneers in the support and development of Asian-Australian artists at a time when such artists were either overlooked by institutions or curated within a culturally-reductive lens. Using various approaches—such as diversity, strategic essentialism and at times even refusing to discuss cultural identity—these two directors helped to counteract the marginalisation and stereotyping of Asian-Australian artists. Furthermore, through a process of inclusive exhibition-making, these directors and curators were able to promote an understanding of the fluidity and multiplicity of Asian diasporic subjectivities.

This essay has been adapted from excerpts from Tian Zhang’s dissertation Between Asia and Australia: Curating Asian-Australian Identities at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, produced in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree Master of Art Curating, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sydney, 2018.

Notes

(1) Melissa Chiu (4A Director, 1997-2001), interview with the author, 31 July 2018.

(2) Newsletters from the time indicate that the AAAA was active from late 1995 and incorporated in January 1996 by Chris Pang, Tek Tan and Cindy Pan, originally with a focus on the performing arts. In 1996, this group merged with a visual arts group with similar interests, which included Vicente Butron, Melissa Chiu, Felicia Kan, Victoria Lobregat, Kim Moore Su-Lin Tse and John Young. Emil Goh, David Lui and Philip O’Toole joined the AAAA prior to establishing the gallery space in December 1996; John Young, email message to author, 3 October 2018.

(3) John Young, ‘Foreword’ in 4A, edited by Benjamin Genocchio (Sydney: The Asian Australian Artists’ Association, 1998), exhibition catalogue, 5.

(4) Cited in Patrick D. Flores, Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia (Singapore: NUS Museum, 2008), 85.

(5) Chiu, interview with the author.

(6) ‘Nonya’ is a term for Peranakan women who were descendants of Chinese immigrants in parts of present-day Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand.

(7) Melissa Chiu, ‘Asian-Australian Artists: Cultural Shifts in Australia,’ Art and Australia 37, no. 2 (1999): 257.

(8) Phillip O’Toole, ‘Gallery 4A: The Changing Face of Australian Art,’ AMIDA 3, no. 3 (1997): 23.

(9) Flores, Past Peripheral, 142.

(10) O’Toole, ‘Gallery 4A,’ 23.

(11) The only Asian-Australian artist in the first APT (1993) was Irene Chou (Hong Kong/Australia). In the second APT (1996), the only Asian/Pacific artist living in Australia was Wendi Choulai. Of around 200 artists in Asialink exhibitions from 1992–1996, only 7 were Asian-Australian. Statistics compiled by the author. Thai curator and critic Apinan Poshyananda criticised exhibitions of Australian art for featuring predominantly white artists, including: Edge to Edge: Australian Contemporary Art to Japan (1988), Australian Bicentennial Authority; Out of Asia (1990), curated by Alison Carroll, Heide Gallery, Melbourne; and Art from Australia (1990) curated by Alison Carroll, Australian Exhibition Touring Agency, Melbourne; Apinan Poshyanda, ‘The Future: Post-Cold War, Postmodernism, Postmarginalia (Playing with Slippery Lubricants),’ in Tradition and Change: Contemporary Art of Asia and the Pacific, ed. Caroline Turner (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1993), 16.

(12) Michelle Antoinette, ‘A Space for “Asian-Australian” Art: Gallery 4A at the Asia-Australia Arts Centre,’ Journal of Australian Studies 32, no. 4 (2008): 535.

(13) Ien Ang borrowed these phrases from the title of Paul Gilroy’s article, ‘It ain’t where you’re from it’s where you’re at,’ in On not Speaking Chinese: Living Between Asia and the West, edited by Ien Ang (London and New York: Routledge, 2001), 30.

(14) Chiu, interview with the author.

(15) Ah Xian continued to develop his porcelain bust sculptures over subsequent years with much success.

(16) Annamese or An’nan refers to type of Vietnamese porcelain. An’nan was part of China after the Tang Dynasty before it was colonised by the French in the 1860s. Intact Annamese ceramics are rare so the shards are also highly regarded.

(17) Ien Ang, ‘Introduction: Alter/Asian Cultural Interventions for 21st Century Australia,’ in Alter/Asians: Asian-Australian Identities in Art, Media and Popular Culture, ed. Ien Ang, et al. (Sydney: Pluto Press, 2000), xxiii.

(18) Melissa Chiu, ‘Introduction’ in Bilingual, (Sydney: Asian Australian Artists Association, 1999), exhibition catalogue, 3.

(19) Chiu had only previously written about this issue in more academic contexts; see Chiu, ‘Asian-Australian Artists,’ 254–256.

(20) These conferences were: the Alter/Asians conference at Customs House, Sydney convened by Ien Ang, Sharon Chalmers, Lisa Law and Mandy Thomas; and the inaugural Asian-Australian Identities Conference at the Australian National University, Canberra, convened by Jacqueline Lo, Helen Gilbert and Tseen Khoo.

(21) See Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2006), 281. Spivak has since distanced herself away from the term; Sara Danius, Stefan Jonsson, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, ‘An Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak,’ Boundary 2 20, no. 2 (1993): 35.

(22) Ang, On Not Speaking Chinese, 36.

(23) After Chiu departed in 2001, Gia Nghi Phung, then-Manager, became the Director until 2002. Linda Goodman was then briefly Director until Huangfu’s arrival in 2003.

(24) Huangfu had emigrated from China to Australia in 1989 during the post-Tiananmen wave before moving to Singapore to develop the Earl Lu Gallery at the LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, Singapore from 1996 to 2003; ‘Investigating Binghui Huangfu,’ Broadsheet 32, no. 4 (2003): 21.

(25) Binghui Huangfu, ‘Asia Australia Arts Centre: Asian Traffic On The Move.’ Asia Art Archive, last modified December 1, 2005.

(26) Binghui Huangfu, ‘Introduction’ in Asian Traffic, edited by Binghui Huangfu (Sydney: Asian Australian Artists Association, 2005), exhibition catalogue, 7.

(27) ‘Investigating Binghui Huangfu,’ 22.

(28) Binghui Huangfu, Asian Traffic, 93.

(29) Ibid., 125.

(30) Huangfu, ‘On The Move.’

(31) Ibid.

(32) Ibid.

(33) Ang, Not Speaking Chinese, 100.

(34) ‘Investigating Binghui Huangfu,’ 22.

(35) Binghui Huangfu, ‘Asian Traffic, Don’t Walk’ in Asian Traffic, 28.

(36) Maura Reilly, ‘What Is Curatorial Activism?’ ArtNews, last modified July 11, 2017, 30.

(37) Ibid., 30-31.

About the contributor

Tian Zhang is an independent curator, writer, facilitator and collective worker based on Dharug Country in western Sydney