The China/Avant-Garde exhibition and Xiao Lu: 30 Years On

Alex Burchmore

Xiao Lu, 2019, pictured in front of her work Polar《极地》(detail), 2016, C-type prints, 80 x 120 cm, editions 1/9 and 5/9, printed 2018 documentation of performance: 23 October 2016, Beijing Live 1, Danish Cultural Center, 798 Arts District, Beijing, China. Photographs by Yi Zhilei. Courtesy the artist. Installation view at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, January 2019. Image: Kai Wasikowski.

Certain names and events have become so enshrined in canonical accounts of contemporary Chinese art that they have taken on almost legendary proportions: the first exhibition held by the Stars in September 1979; the outpouring of creativity associated with the ‘85 New Wave; the combative display of works in Fuck Off, timed to coincide with the 3rd Shanghai Biennale in 2000 by its artist-organisers Feng Boyi and Ai Weiwei. China/Avant-Garde, held from 5–19 February 1989 at the National Art Museum of China (then the National Art Gallery), Beijing, is commonly positioned as a watershed between these events, the last gasp of the New Wave and first breath of the cynicism, anger and antagonism that came to characterise the 1990s. A similar mediating role is attached to the artistic act for which Xiao Lu is most widely-known, now referred to as The Gunshot Event: the firing of a gun into her installation Dialogue (1989; Duihua 对话), one of over 300 works by 186 artists shown in China/Avant-Garde. Following this incendiary act—that not only contributed to the exhibition’s early closure, but also led to Xiao’s three-day interrogation—and given added incentive by the violence in Tiananmen Square over subsequent months, Xiao Lu chose to relocate to Australia in December 1989, where she remained until her return to Beijing in November 1997.

Three decades later, The China/Avant-Garde exhibition and Xiao Lu: 30 Years On, a one-day workshop at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (4A) on 1 February 2019 initiated and organised by Claire Roberts, ARC Future Fellow and Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Melbourne, in association with the exhibition Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue 肖鲁:语嘿 curated by Roberts, Mikala Tai and Xu Hong, provided an opportunity to reflect on the significance of those events. Surrounded by Xiao Lu’s work, guest speakers and audience members explored a range of perspectives on the artist and the exhibition with which she is indelibly associated, documentary photographs of which were displayed in the gallery space alongside other rarely-seen ephemera. Xiao Lu herself sat among the audience, silent for the most part but a palpable presence nonetheless, a witness to the sincerity and authenticity of her prolific artistic practice.

The pairing of the two displays at 4A, one archival, the other deeply personal, prepared participants for a comparable contrast in the day’s proceedings between analysis of historical, social and artistic contexts for China/Avant-Garde, and a close engagement with Xiao’s eclectic oeuvre. Dialogue, her most widely-recognised creation, was also read from divergent points of view—a crystallisation of socio-political and cultural conditions in China at the end of the 1980s and, alternatively, as a self-expressive engagement with the issues of gender, bodily identity and spiritual frustration that the artist has interrogated throughout her career. The exchange (or dialogue) between these perspectives left a deep impression, encouraging participants to reflect on their own understandings of the past and to interrogate how the historical is often retrospectively co-opted as a catalyst for present and future developments, sometimes at the expense of more nuanced points of view.

Xiao Lu herself sat among the audience, silent for the most part but a palpable presence nonetheless, a witness to the sincerity and authenticity of her prolific artistic practice.

Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue 肖鲁:语嘿 (installation view); Tables: China/Avant-Garde exhibition archival materials. Back: Xiao Lu, Dialogue (对话 ), 1989, C-type print on vinyl, documentation of installation, and performance: 11.10am, 5 February 1989, China/Avant-Garde exhibition, National Art Gallery, Beijing; reproduced courtesy Wen Pulin Archive of Chinese Avant-Garde Art and Xiao Lu. Projection: China/Avant-Garde exhibition, set of 210 archival 35mm colour transparency slides produced by Fine Arts Magazine, 1991. Private collection. Far Left: Wang Youshen, China/Avant-Garde exhibition. Before and after the ‘Shooting Incident’ (detail), 1989 – 2019, inkjet prints, dimensions variable, courtesy Wang Youshen; photo: Kai Wasikowski, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2019; courtesy the artist.

Claire Roberts, introduction

Claire Roberts opened with brief remarks acknowledging the exhibition and workshop as part of her ARC-funded research project Reconfiguring the World: China. Art. Agency. 1900s to Now, and expressing gratitude for the support given by the University of Melbourne and the Australia-China Council. Roberts first reiterated the great significance of both events, reminding the audience that this is the first retrospective of Xiao Lu’s work to be held in Australia, China or elsewhere in the world, a surprising (and revealing) distinction given the central role Xiao has played and continues to play in the development of contemporary Chinese art. Roberts also noted the sensitivity that even now surrounds the events of 1989 in China, the passions, tensions and even risks that discussion of China/Avant-Garde can arouse, demonstrating its on-going relevance to the social, political and cultural situation in that country.

Several themes emerged in Roberts’ remarks that resurfaced throughout the day. Foremost among these was the persistent marginalisation of women in the Chinese art world and lack of critical attention given to artists like Xiao Lu, in China and elsewhere. This disparity, as several speakers discussed at greater length, has engendered a distinctly one-sided view of modern and contemporary Chinese art in which the perspectives of a select group of male artists are elevated to universal significance while their women colleagues are ignored. Beijing-based art historian, curator and critic Xu Hong, speaking from first-hand experience as an artist and curator practicing since the early 1980s, positioned this prejudice within the historical context of women’s representation in art and literature. Using Xiao’s performances as a case-study, she revealed some of the unique and largely overlooked perspectives that women can express and underlined the urgent need to incorporate these points of view into our readings of Chinese art. Yu-Chieh Li, the current Judith Neilson Postdoctoral Fellow of Contemporary Art at the University of New South Wales, drew attention to another overlooked figure, photographer Xing Danwen, discussing the potentially subversive ‘“female gaze’” in her photographs of male artists Ma Liuming and Zhang Huan. Comparing Xing’s portrayal of Ma with the canonical images of this artist taken by Rong Rong, Li exposed the limits of a dominant artistic masculinity by showing the privileging of a self-assertive machismo over more androgynous forms of gender identity.

Another theme that Roberts raised was the significance of Australia in the story of Chinese contemporary art, not only as a place of refuge but as a centre for art-historical scholarship. Xiao Lu is one of many artists who sought political asylum here after 1989 and inspired what Nicholas Jose described in his contribution to the workshop as a ‘“U-turn’” in popular attitudes toward China. As Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy in Beijing from 1987 to 1990, Jose was closely involved in these demographic and attitudinal shifts, while the many books and articles that he, Roberts and John Clark, among others, have published from the 1990s to the present continue to direct scholarly debates, nationally and internationally. An impressive concentration of Australian academic, curatorial and artistic knowledge gathered for the workshop, including many speakers and other participants who have played a pivotal role in fostering public awareness not only of Chinese, but Asian art and culture in general. And what better forum than 4A, a facilitator for dialogue, advocacy and community development since its founding in 1996.

Xiao Lu, China/Avant-Garde exhibition archival materials (detail); photo: Kai Wasikowski, Impossible Dialogue 肖鲁:语嘿, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2019; courtesy the artist.

Xu Hong, Looking back on the ’89 China/Avant-Garde exhibition

Following her opening remarks, Roberts welcomed leading artist, curator and art historian Xu Hong, former Head of the No. 1 Academic Department at the National Art Museum of China, to take the floor for the first of her two papers. Xu set the stage for subsequent discussions with a summary of the political, social and cultural shifts that created the conditions necessary for China/Avant-Garde. In most accounts of the development of Chinese art, the exhibition of work by the Stars in 1979 is used as a convenient opening chapter, yet Xu observed that many changes retrospectively attributed to the impact of this exhibition can be identified with the preceding decade. During the 1970s, she recalled, ‘life was like a river about to dry up’—China was facing a national crisis, and feelings of disillusionment with revolutionary struggle after the Cultural Revolution were widespread. Art, especially painting, became an avenue for escape and a source of comfort for many afflicted by the hardships of those years, inspiring tranquil landscapes, still-life studies, and intimate portraits of family and friends that provide a stark contrast to the strident, contrived canvases of academy-taught Revolutionary Realism. To avoid condemnation for works that would be deemed ‘“unacceptable’” if shown in public, however, many aspiring artists painted at home—including those who taught and studied in the academies, who used their training to document their lives or create counter-narratives that undermined the certainty of propaganda.

In addition to the minutiae of the everyday, Xu explained that an interest in European artistic and philosophical ideas also provided inspiration, presaging the receptivity later associated with the 85 New Wave. Imported art journals and magazines not only inspired new styles and subjects but offered a much-needed alternative to government-endorsed texts. Isolated from their families—and from direct government control—students who had been ‘“sent down’” to the countryside for re-education began to form clandestine artistic groups, sharing their work and inspiring a mutual desire for change. Recalling her own experience during these years, Xu asserted that this broadening of horizons, and especially the interest in ‘“bourgeois’” forms of abstraction, should be considered the initial phase in the transformation of modern art from state-sanctioned school into oppositional aesthetic tendency. The innovations of this decade, hidden from public view but ground-breaking for those involved, created a pervasive desire for change that came to fruition during the 1980s, and it was their subsequent development in art, literature and the social sciences that inspired the organisation of China/Avant-Garde.

This exhibition, then, in which both Xu Hong and Xiao Lu participated, appeared to mark the much-anticipated breakthrough of a counter-cultural movement that had been growing for two decades. Yet, as Xu explained in more depth in her second paper discussed below, it also exposed the extent to which certain prejudices—like the marginalisation of women artists—remained entrenched, while an ensuing government crackdown on the arts revealed that the overbearing political climate of the 1970s had not entirely dissipated. Even today, the ban on performance and installation instituted at the National Art Museum of China to guard against the possibility of another incendiary gesture remains in force, though Xu remarked that this prohibition can be circumvented—for example, by classifying an installation as ‘“sculpture’”. It is this ability to evade regulation and the range of expression that such evasion encourages, Xu concluded, that have come to exemplify Chinese art after 1989: ‘since China/Avant-Garde, plurality and diversity rule.’ And it is also in this adaptable reliance on personal resources that the legacy of the 1970s most clearly emerges as an initial phase in the development of Chinese contemporary art, a decade of perseverance and commitment to an intimate yet immediate aesthetics of eclecticism, gazing both outward and inward at the same time.

It is this ability to evade regulation and the range of expression that such evasion encourages, Xu concluded, that have come to exemplify Chinese art after 1989: ‘since China/Avant-Garde, plurality and diversity rule.’

Nicholas Jose, The U-turn comes south

Nicholas Jose, writer, academic and former Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy in Beijing (1987–90), complemented and further enriched Xu’s clarification of the social, cultural and political circumstances for China/Avant-Garde with a discussion of its impact outside of China, in the very different context of Australia in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Coinciding with his tenure as Cultural Counsellor, the most significant event of these years was the bicentennial commemoration of colonisation in 1988, which also happened to mark a decade since the founding of the Australia-China Council, after which cultural exchanges between Australia and the People’s Republic of China became more frequent. Jose remembers this as a ‘high-water mark’ for international affairs, and a time when the ‘White Australia attitudes’ that had formerly haunted Australian views of the outside world faced mounting opposition.

Aside from the bicentennial, Jose recalled three other events that captured the spirit of these years in especially resounding terms, creating a setting in which China/Avant-Garde took on special importance. The first was the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s ‘“Fine Arts Delegation’” sent to China in 1988 to encourage artistic exchange. The delegates chosen—Betty Churcher, Director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia (1987–90) and later Director of the National Gallery of Australia (1990–97); David Williams, Director of the Canberra School of Art, Australian National University (1985–2006); and Geoff Parr, Head of the Tasmanian School of Art, University of Tasmania (1978–94)—returned to Australia with a great sense of purpose and played key roles in the broadening of public perceptions of Chinese art by staging innovative exhibitions, organising artist residencies, and developing more inclusive curricula. Following this, Jose recalled that the reciprocal awareness of Australian art generated in China by the exhibition Contemporary Australian Art to China, 1988-89, jointly organised by the Australian Embassy in Beijing and China’s Ministry of Culture, further strengthened diplomatic and cultural ties. Significantly, this exhibition included work by two of the artists who would later be involved in the founding and early activities of 4A: Lindy Lee and Tim Johnson. The third event that Jose recalled as symptomatic of these years was another exhibition, held just a few months after China/Avant-Garde at the Centre Pompidou, Paris: Magiciens de la terre, which brought together over one hundred artists from fifty countries. In addition to curator Jean-Hubert Martin’s unprecedented pairing of Chinese and Australian Aboriginal works, Jose recalled that Magiciens created ‘a new frame of reference for cross-cultural relations’ that significantly impacted the reception of China/Avant-Garde in Australia.

This reception was profound and far-reaching—‘an actual U-turn that has continued [to exert an influence] until today,’ despite an inevitable backlash. Many works in the exhibition were later acquired by Australian collectors and galleries, establishing a solid foundation for what are now world-class collections of contemporary Chinese art, while several of the artists involved (including Xu Hong) also took part in Roberts’ ground-breaking exhibition Post-Mao Product: New Art from China, shown across Australia from 1992 to 1993. On a broader social level, the exodus of Chinese artists and intellectuals in the wake of government oppression after the events of 1989, in conjunction with the growth of the export education industry in Australia from 1988, precipitated what commentators described as a ‘“China crisis’”. Rather than a crisis, however, Jose argued that this new wave of Chinese migration is ‘something to celebrate,’ a cultural stimulus comparable in scale to the welcoming of Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s that cultivated Australian familiarity with China and Chinese people to an extent not seen since the nineteenth century. With the rise of political antagonists like Pauline Hanson and the election of John Howard as Prime Minister in 1996, however, these developments were curtailed and the atmosphere of inclusivity and tolerance was stifled, to be replaced by one of paranoia and prejudice. 1996 also saw the founding of 4A as a new space in Sydney for the exploration of Asian and Asian-Australian identities, pointing to wider social tension between a fascination with Asian cultures and an anxiety about the increasingly visible presence in Australia of Asian peoples. This tension has not abated and has even been heightened in recent years by Hanson’s re-emergence, the election in the United States of a leader opposed, like Howard, to cosmopolitanism, and the rise of Brexit and other populist movements that endorse an isolationist view of the world. As events like this workshop and exhibition make clear, however, a desire for cultural exchange has remained strong, fostered and given voice by institutions like 4A—there is hope that we may encounter another U-turn in public opinion.

Xiao Lu, 15 Gunshots… From 1989 to 2003, (15枪…从1989 到 2003) (installation view), 2003, 15 black-and-white digital prints, framed and then punctured by a bullet, 100 x 45 cm, printed 2018, edition 12/15, photographs by Li Songsong; photo: Kai Wasikowski, Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue 肖鲁:语嘿, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2019; courtesy the artist.

John Clark, Problems in the constitution of a late twentieth century Chinese avant-garde, with cross-Asian comparisons

In her brief introduction for the third speaker of the day—John Clark, Professor Emeritus in Art History at the University of Sydney—Roberts drew attention to his formative and enduring role in the development of Asian art scholarship in Australia. In 1991, a year before Roberts’ Post-Mao Product, Clark initiated and organised a conference dedicated to ‘“Modernism and Postmodernism in Asian Art’” at the Australian National University that introduced scholars from around Australia, many for the first time, to their peers in Asian nations, including such luminaries as Thai scholar Apinan Poshyananda, Japanese film historian Inuhiko Yomota, and Korean art historian Kim Youngna. Clark’s participation in the workshop therefore marked a significant step toward one of the Centre’s own objectives, also given voice in 2016 at 4A’s Twenty Years symposium, to strengthen ties with the field of art history and make the work of leading scholars accessible for a broader audience, outside the usual paywalls (and other barriers) of academia.

Like Xu Hong, Clark focused on the imposition of grand narratives within art history and their frequently exclusionary, distorting effects. He emphasised the need to avoid stereotypes that reduce the artist to a ‘bearer of spectacle,’ rather than an individual working in specific social and historical circumstances. While Xu spoke from personal experience, Clark drew on the formidable breadth and depth of his scholarship to accomplish this aim, shedding light on the often-overlooked continuity linking the Chinese avant-garde of today with that of the early twentieth century. Although the idea of an avant-garde in China is conventionally associated with the reception of European and North American influences in the 1980s, a similar creative revitalisation took place long before this in the 1920s and 1930s. During these decades, artists like the renowned painter Xu Beihong (1895–1953) used their knowledge of European styles, techniques and subject-matter to formulate new perspectives on Chinese schools of artistic practice. Comparing this situation with that several decades earlier in Japan, and a decade later in India, Clark emphasised the role of both local and imported discourses for such efforts at renewal, and especially the essential position of the academy not just as a target of artistic opposition but a source of validation. However, while the romance of a modernised national tradition in Japan and the struggle against colonialism in India fostered strong avant-gardes, in China the post-1949 enlisting of Xu Beihong and other avant-gardists as tools of the state stifled the conditions of experimentation necessary for such tendencies to grow. Innovative fusions of local and imported discourses were subsumed within the manufacture of historical dioramas glorifying the nation, while the literati connoisseurs who had previously comprised the principal audience for such artists were replaced by a projected viewership of idealised Chinese citizens.

From its origins in the early twentieth century, then, avant-gardism in China, as elsewhere in the world, was closely tied to the academy, and the relationship between ‘“official’” and ‘“non-official’” art, as Clark has stressed in his many published writings, is not as straightforward as it seems. Another parallel can be drawn here with Xu Hong’s remarks about the involvement of academically-trained artists in the underground artistic innovations of the 1970s, despite an assumption that their creative output was limited to Revolutionary Realist canvases. Even in the 1950s, Clark observed, Dong Xiwen (1914–73), best-known for his Socialist Realist paean The Founding Ceremony of the Nation (Kaiguo dadian 开国大典; 1953), nurtured a secret passion for Impressionism, post-Impressionism and abstraction, and clandestinely shared imported exhibition texts with his students while, outside the academy, such materials were stridently denounced. For Clark, the continuity of this covert experimentation with the more visible innovations of the 1980s is clear, despite the protests of European and North American writers who prefer more heroic, explosive narratives.

The broader point raised by the overlapping of mainstream and counter-culture, to cite Clark, is that ‘the avant-garde develops with the consent of the academy.’ In other words, subjects and forms of expression considered revolutionary can only gain visibility if they conform to an accepted level of subversion. On the other hand, those artists, like Xiao Lu, who dare to work outside this mutually reinforcing relationship, are marginalised because the complexity of their work threatens to upset the balance. Speaking of the 1930s, Clark cited the example of another artist who faced exclusion because her art proved too transgressive: Pan Yuliang (1895–1977), the first woman in China known to have painted a nude female figure. The only surviving trace of this ‘uncomfortably direct representation of a tabooed subject,’ however, is a magazine illustration—the original was violently defaced, abandoned and forgotten. Like Xiao Lu several decades later, Pan was forced to contend with the prejudice of a patriarchal art system, while her work, though not unusual in subject-matter (her male colleagues also painted nudes), suffered by association with her denigrated gender. The same biases remain today, with the inclusion of ‘“feminist’” works in exhibitions in China and elsewhere decided by their portrayal of acceptable subjects, like the one-child policy, while artists who break from these limits to address broader ‘problems of phallocracy’ are denied recognition.

Modern, contemporary, or avant-garde?

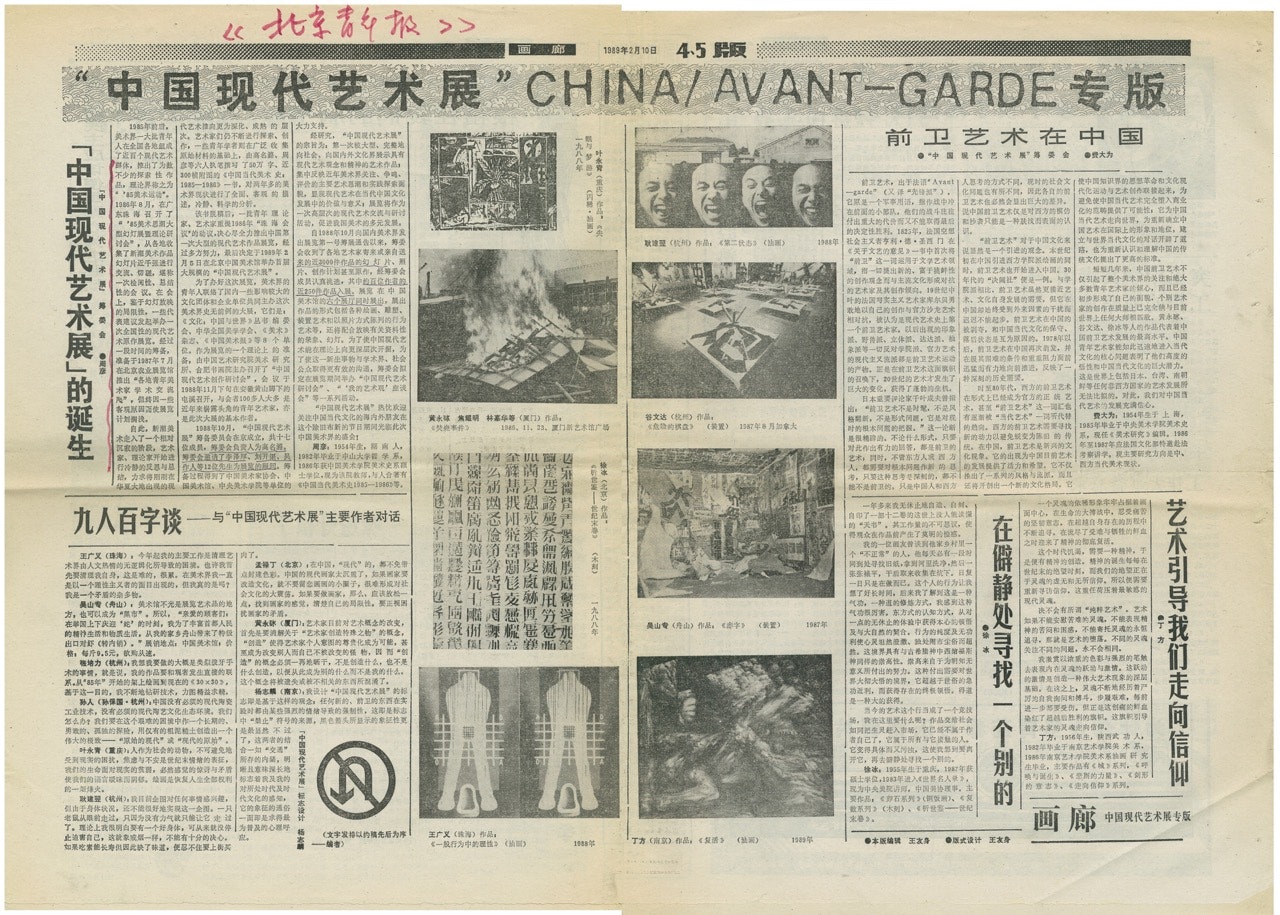

Clark’s paper was followed by a lively discussion of the contention that sometimes surrounds issues of naming in the study of Chinese art. Reflecting on the anachronistic application of the term ‘“avant-garde[‘” to artists of the 1980s, Roberts noted the discrepancy between the title China/Avant-Garde and the name by which this event is known in China: Zhongguo xiandai yishu zhan (中国现代艺术展). Literally, this reads ‘“Chinese modern art exhibition,’” with the words ‘“avant-garde’” (qianwei 前卫) conspicuously absent. Roberts and other speakers noted that this terminological substitution reflects the imposition, as exposed by Clark, of a narrative that artificially divides the history of Chinese art into discrete episodes. For much of the last century, including the 1980s and 1990s, artists in China referred to themselves as creators of the modern, a term associated with a progressive social attitude, aesthetic innovation and an opposition to the imperial regime. The designation ‘“contemporary’” (dangdai 当代) appeared during the 1990s and only replaced xiandai as preferred term after the millennium, reflecting increasing international interest in Chinese art and the creation of the so-called ’79 Narrative to support the illusion that artistic innovation was solely a product of external influences. Qianwei or ‘“avant-garde,’” on the other hand, has revolutionary connotations that give it a political edge. Before its association with contemporary art, qianwei was used to describe the work of early twentieth-century printmakers and other artist-participants in the New Culture movement who supported the Communist cause. To apply it to an exhibition of experimental works in 1989 could therefore have been read as a statement of affiliation with the socially constructivist aims of this movement, and as a potential opposition to the new regime of the Chinese Communist Party. The nuances of the terms avant-garde, modern and contemporary could be discussed at length, though even these brief remarks suffice to show their relevance for the interrelationship of mainstream and counter-culture, local and foreign to which Clark drew attention in his paper.

Wang Youshen, ‘The sound of gunshots in the art gallery’ (newspaper page), Beijing Youth News (Beijing qingnian bao), 10 February 1989, p.8. The article includes a statement signed by Tang Song and Xiao Lu regarding the artistic intention of the shooting incident and a photograph by Wang Youshen.

Olivier Krischer, Another Asia: The China Avant-garde exhibition and Japan

Like Jose, Olivier Krischer—Deputy Director of the China Studies Centre, University of Sydney—focused in his paper on the impact of China/Avant-Garde outside of China, though in Japan rather than Australia. In contrast to the outward-looking cultural efflorescence typified by the dynamic eclecticism of the ’85 New Wave in China and the diplomatic optimism of Australia’s Fine Arts Delegation, Krischer explained that the 1980s in Japan were marked by an increasing awareness of the untenability of that country’s rapid economic expansion. Stock and housing prices were inflated to prodigious heights, prompting those who recognised the risks of this situation to direct their ambitions away from a desire for global economic dominance toward a more conservative vision of pan-Asian solidarity. This vision of regional identity was strongly inflected by a paternalistic, empire-building line of thought that had lingered since the early decades of the century—a legacy of Japan’s largely unaddressed identity as an imperial nation prior to World War II. In the field of culture, such attitudes were reflected by the persistence of an anthropological perspective on Chinese art, despite the presence of Chinese artists and students across the country. These included such luminaries as Huang Rui, a founder of the Stars who moved to Japan in 1984, and Fang Zhongming, who lived in and travelled between both countries throughout the 1980s. Most Chinese art exported for display in Japan at this time, however, was drawn from state-approved National Exhibitions and reflected a narrow view of contemporary practice.

In this social, political and cultural climate, China/Avant-Garde stimulated a shift in dominant understandings of Chinese art and, as in Australia, prompted closer engagement with artists’ lived realities. In the wake of the fanfare and furore sparked by the exhibition, many Chinese artists resident in Japan—including future art-stars like Cai Guo-Qiang—sought to associate their work with this excitement, to ‘insert themselves into the narrative.’ Cai, for example, wrote a glowing review of China/Avant-Garde for a Japanese arts magazine, often overlooked now, in which he not only presaged the subsequent preoccupation in the Chinese art world with conceptual and installation works but also drew a parallel with Magiciens de la terre in the work of Gu Dexin, who participated in both exhibitions. Cai’s enthusiasm was shared by many Japanese artists, patrons and gallerists, who had been a source of early interest and support for artists in China during the 1970s and 1980s. Krischer noted the efforts of one gallerist as especially significant: Tabata Yukihito of Tokyo Gallery, a celebrated venue for European and North American artists since the 1950s. Seeking to broaden the gallery’s purview, Tabata travelled to Beijing for China/Avant-Garde a few days before its final closure, taking photographs and interviewing artists, and was one of the very few overseas visitors to acquire works in the same year. Although shipment of these was delayed by the events of June 1989, Tabata was nonetheless able to include them in his pioneering exhibition Chinese Contemporary Art ‘Now’ in July—the first significant display in Japan of current Chinese work that challenged existing narratives, and one of the earliest organised responses to China/Avant-Garde outside China.

Despite this history of close engagement between China and Japan so early in the narrative of contemporary Chinese art, Krischer drew attention throughout his paper to the persistent lack of critical recognition given to this relationship. He attributed such oversight above all to the enduring authority of an ‘“East meets West’” narrative in conventional understandings of art’s globalisation, even in China itself. Work by Chinese artists resident in Japan, for example, is frequently overshadowed by that of artists in New York or Sydney. This narrative positions Europe and North America (and, to a lesser extent, Australia) as central to any broadening of global horizons, marginalising ‘“regional’” networks of exchange even though, in many cases, these have exerted a more powerful influence for a greater length of time. Like Jose and Clark, Krischer emphasised the pressing need to consider these overlooked connections, to question and complicate existing accounts of Chinese art. Once again, Australia has been a centre for the development of these lines of inquiry, with scholars including Clark, and US-based Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen, to name only a few, pioneering the study of a broader Asian context for Chinese modern and contemporary art. Krischer concluded with a warning, however, that Japan is not a ‘missing hero’ to be appended to a universal narrative, but rather that Japanese reception of China/Avant-Garde should be used to question heroic determinism, enabling more nuanced and sensitive interpretation.

The explosive traces of her actions on the paper beneath her feet were clearly intended to recall the schools of ink-painting and calligraphy historically practiced by China’s Confucian literati elite, a conventionally male-dominated sphere of artistic activity transgressed and subverted by the artist’s feminine, bodily presence.

Paul Gladston, Beyond Dialogue: Interpreting recent performances by Xiao Lu (with Lynne Howarth-Gladston as co-author)

Re-opening the day’s proceedings after a break for lunch, Paul Gladston—the inaugural Judith Neilson Chair of Contemporary Art at the University of New South Wales—initiated a shift in focus from the broader context of China/Avant-Garde to the more specific dynamics of Xiao Lu’s oeuvre. Although, like the artists, art historians and arts writers who spoke during the morning, Gladston has written extensively about contemporary Chinese art, publishing a series of highly-regarded books as well as a multitude of influential journal articles, he began with an admission that his area of expertise is critical theory, not art history. What followed was a nuanced and sensitive discussion of the theoretical debates raised by Xiao’s work in the thirty years since The Gunshot Event.

During the 1980s, Gladston explained, the Chinese avant-garde was animated by a desire to preserve the ‘“purity’” of art in the face of its propagandistic mobilisation by the state, and in contrast to the avowedly political aims of European avant-gardes. Xiao’s decision to fire a gun at her work, however, was immediately framed as a radical gesture and ‘rallying-point for pro-democratic, anti-authoritarian dissent,’ retrospectively named ‘the first shots of Tiananmen’ despite the artist’s description of it as a purely aesthetic act in a written statement submitted to authorities several days later. More recently, Xiao’s shots have also been termed the first significant artistic statement in China of a feminist perspective, drawing criticism from the (primarily male) arts establishment who argue that this accolade detracts from their alleged political ramifications. Rather than a straightforward opposition of patriarchal and feminist viewpoints, however, Gladston explained that this disagreement reflects a broader discursive struggle overlooked by external commentators. Since the growth of a specifically ‘feminist art’ (nuxing yishu 女性艺术) in China from the mid-1990s, it has been tied to a host of ‘post-modernist identitarian’ tendencies, including post-structuralist and deconstructionist schools of thought, perceived by critics as a threat to social cohesion and Chinese civilisational values. Although it is tempting to conflate such objections with conservative arguments in Europe, Australia and the US, Gladston cautioned that we must recognise their validity as a legacy of ‘durable resistance to Western colonialism-imperialism’ among Chinese scholars since the nineteenth century, while also recognising the importance of Xiao’s feminist position. In other words, we must position The Gunshot Event as ‘part of a continuing discursive struggle rather than [a] definitive art-historical fact.’

In the second half of his paper, Gladston demonstrated one possible means to shift discussion of Xiao’s work beyond such disputes by turning to a more recent piece, One (2015), in which the artist engages with Chinese tradition. For this work, photographs of the performance of which at the University of Gothenborg’s Valand Academy were hung on the wall of the gallery facing Gladston, Xiao stood on a large sheet of xuan paper, clad only in a loose-fitting, white cotton dress, and up-ended a plastic bucket of black ink over her head, followed by another filled with water, in a meditative, almost trance-like state. The explosive traces of her actions on the paper beneath her feet were clearly intended to recall the schools of ink-painting and calligraphy historically practiced by China’s Confucian literati elite, a conventionally male-dominated sphere of artistic activity transgressed and subverted by the artist’s feminine, bodily presence. At the same time, however, Gladston explained that Xiao’s actions can also be read as an enactment of Daoist principles of non-dualist reciprocity between opposites: the intersection and mutual dependence of the feminine principle yin with the masculine principle yang. Her performance can therefore be linked with both a European identitarian perspective, as an act of feminist reclamation, and a Chinese Confucian/Daoist point of view, as ‘a spectral manifestation of differentiated but uncertainly-bounded selves already implicit to a non-rationalist literati aesthetic.’ Each interpretation is valid, and each reflects discursive conditions within a specific socio-cultural and historical context. As in the case of The Gunshot Event and the fierce debate that it still arouses among different invested parties, it is in the evolving tensions and resonances created by the co-existence of these viewpoints, Gladston concluded, that the significance of the work arises.

Xiao Lu, Polar 极地, 2016, documentation of performance, 23 October 2016, Beijing Live 1, Danish Cultural Center, 798, Beijing, China; photo: Yi Zhilei. courtesy the artist.

Xu Hong, Butterfly effect: Xiao Lu’s artistic transformation

In her second paper of the day, Xu Hong also shifted attention from the broader context and effects of China/Avant-Garde to the enduring themes of Xiao Lu’s oeuvre, often overlooked in accounts of her work that focus solely on The Gunshot Event. Xu described this performance as both a release of frustrations that had been building for many years and a puncturing, literally and figuratively, of past constraints to open a passage for the ‘fresh air’ of the future. Drawing attention to the photographic prints of a man and woman on the telephone booths comprising Dialogue, their backs turned to the viewer and their conversation disrupted by the dangling telephone receiver between them, Xu positioned the work as an allegory for the history of interaction between genders in China. In literary descriptions of women’s bodies, like those in the Zhou-dynasty (c.1046-256 BCE) Book of Songs or Ming-dynasty (1368-1644) novel The Golden Lotus, women are tied to stereotypes of femininity intended to appeal to male sexual desire. It is this history and its implied reduction of women to bodily experience, Xu asserted, that drove Xiao to shoot her work in a symbolic attempt to shatter the manacles of expectation imposed on her and generations of women before her. This cathartic release, however, so central to her actions, was obscured by the misattribution of the genius behind her gesture to her partner at the time, artist Tang Song, and by the mass of critical perspectives that have accumulated around the work over the past thirty years. For Xu, both this art-historical accumulation and the initial misattribution can be read as attempts by art-world insiders to insert Xiao’s subversive act into the accepted mythology of Chinese art, with its pantheon of invariably male artist-heroes. Yet another instance of a woman’s marginalisation for daring to surpass the assigned limits of avant-gardist innovation, and of the assimilation of individual motives to the universalising imperatives of a grand narrative.

The performances Xiao staged after Dialogue, however, have posed a consistent challenge to the continuity of this narrative, compelling viewers and commentators alike to confront the gendered norms of art-world institutions and the uncontrollable dimensions of meaning that women can wield to disrupt this self-affirming circuit. To a certain extent, Xu explained, the bodily experience to which femininity has historically been tied remains a primary source of inspiration—yet this is not the body constructed by and for the male gaze, circumscribed by desire. As expressed in works like Xiao’s impromptu performance at an event associated with the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, for which she stripped naked in the hallowed confines of a church, jumped into one of the city’s notoriously polluted canals and swam a few strokes, this is the body as ‘an obstacle to aesthetics,’ an organic excess that transgresses all constraint. For Xu, these are works in which the body is ‘allowed to be alive.’ Bodily experience is also expressed in such performances, however, as a conceptual category that gives voice to the relationship between mortality and immortality, or between form and essence. In the Venice performance, Xiao bared the signs of her aging and exposed her naked flesh to the elements, enduring a baptismal immersion from which she emerged cleansed of any illusions about her impermanence. The subjection of the body to trials of endurance is a recurring theme in Xiao’s oeuvre—appearing again, for example, in Polar (2016), for which she planned to carve her escape from a cell of ice but during which she accidentally cut open her hand with the knife intended as a tool of liberation, smearing blood across the unyielding walls of her prison. Yet ordeals such as this, like the puncturing of Dialogue and the scrutiny that Xiao subsequently faced, only increase her almost mystical power to transgress artistic and gender norms. And this transgression is accomplished by a union of bodily experience with spiritual speculation that Xu identified as a key resource for all women artists and critics.

Xiao Lu, Dialogue (对话 ), 1989, documentation of installation and performance: 11.10am, 5 February 1989, China/Avant-Garde exhibition, National Art Gallery, Beijing; reproduced courtesy Wen Pulin Archive of Chinese Avant-Garde Art and Xiao Lu.

Archibald McKenzie, Xiao Lu’s performance art in context—personal and international

Like Gladston, musician, linguist and lawyer Archibald McKenzie prefaced his paper with the caveat that he, too, was ‘an art-world outsider’ and so couldn’t speak with the same authority as the artists and art historians who took the floor before him. Yet McKenzie has long enjoyed a close friendship with Xiao Lu, the most visible product of which is his translation into English of her autobiography Dialogue (2010), while his experience as a dance accompanist has given him a finely-tuned sensibility to the choreography and theatre of performance. What’s more, as a Chinese-language specialist and prolific translator of books, articles and academic papers on modern and contemporary Chinese art, McKenzie’s understanding of these areas of study is more profound than his humility allows him to concede, though the depth of his knowledge became evident as he spoke. He observed, for instance, that a parallel can be drawn between Xiao’s performances and those of Serbian artist Marina Abramović, especially in their shared exploration of interpersonal relationships and coming-to-terms with femininity as a source of constriction and self-expression. Xiao and Abramović are also leading figures, he noted, in the development from the 1970s of feminist performance art, authoring idiosyncratic responses to the disconcertingly similar pressures confronting women in their radically different cultural contexts. McKenzie again prefaced his remarks, however, with a caveat about the difficulty of defining performance as a category of artistic practice, not only because it lacks a medium of its own but also because performative elements can be found in many forms of art—the oscillation of Dialogue between installation and performance being a case in point.

Leaving aside such ambiguities of definition, McKenzie eloquently elaborated on some of the interpretive points raised by Xu, identifying The Gunshot Event and Xiao’s later performances with a fusion of visceral shock and meditative contemplation. He drew attention once again to the expression of pent-up frustration and cathartic release in these works, framing them as the artist’s response to provocation—in the case of her Venice performance, for example, Xiao exposed herself against the wishes of the event’s organisers, who sternly opposed what they saw as a ‘sacrilegious’ display of nudity. This prohibition and Xiao’s refusal to comply can be positioned within the heritage of attempted control and irrepressible perseverance to which Xu referred, challenging the authority of a patriarchal institution with the fleshliness of her vulnerable yet overwhelmingly present body. McKenzie traced a possible inspiration for the violence of such acts of exposure and endurance, as well as Xiao’s use of instruments of bloodshed like guns or knives and her evocation of hostile elements like ice, to her childhood and adolescence during the Cultural Revolution, when suffering and survival consumed the lives of many people across China. Rather than turning to art as an escape, however, in the tradition of the landscape, still-life and portrait studies of the 1970s, Xiao used her artistic practice to create a space in which these memories could be exorcised and redeemed. Rather than a duality of mind and body, public and private, she united these spheres of existence to generate a holistic ‘being-there’ that both expresses her sorrow for ‘the loss of a utopian dream’ and her ‘longing for unity’—an aspiration McKenzie identified with many performance artists, inside and outside of China. Once again, then, the discussion returned to the multifocal perspective of Xiao’s performance art, reflecting on the hardships and constraints of the past while opening a passage to an unknown but hopefully more open, inclusive future.

Yu-Chieh Li, Xing Danwen’s East Village: Gender, photography, and performativity

In the final paper, Yu-Chieh Li, Judith Neilson Postdoctoral Fellow of Contemporary Art at the University of New South Wales, delved even further into the questions of gender identity raised throughout the day, using the work of photographer Xing Danwen to tease out some of the more theoretical implications of nudity, sexuality and patriarchal norms in performance art. Xing is best-known for her photographs of life in the East Village, an artist-community on the outskirts of Beijing that has been enshrined in the historical narrative of contemporary Chinese art as an important centre for a particular type of performance, typified by the work of Zhang Huan. In pieces like his iconic 12 square meters (1994), for which he sat naked in a public latrine, his body coated with honey and fish oil to entice the swarming flies of summer, and 65 kilograms (1994), for which he was suspended from the ceiling of a claustrophobic room while doctors extracted 250 mL of his blood, only to evaporate it on a hotplate, Zhang cultivated a hyper-masculine persona by testing the limits of his physical endurance. In the black-and-white photographs that record these performances, the artist appears with shaved head and muscular physique, impassive, immovable, stern and unflinching: a portrait of the stereotypically “masculine” characteristics of rationality, self-possession and physical power.

Despite the canonical authority of such images and the patriarchal norms to which they can be made to conform, however, other manifestations of gender identity were explored in the East Village that were more transgressive and less easily absorbed into the standard narrative. These are visible above all in performance pieces staged by Ma Liuming, and especially in the photographs of these performances taken by Xing Danwen. Alongside Zhang Huan, Ma was one of the most prolific artist-residents of this short-lived avant-garde community and yet, although his works have received some critical attention, they have not been endowed with the same quasi-mystical aura. Drawing attention to a further disparity in recognition between Xing’s photographs of Ma and the better-known images taken by Rong Rong, another East Village resident, Li identifies these discrepancies with an attempt to marginalise the disruptive power of the “female gaze”. In his photographs of Lunch (1994), for example, a performance for which Ma, nude and long-haired, quietly prepared a meal in the guise of his feminine alter-ego Fen-Ma Liuming, Rong Rong adopted the documentarian style used for his images of Zhang, recording the artist’s actions in an iconic, detached style. In Xing’s images of the same performance, however, her use of expressive, oblique angles draws the audience into the frame, breaking the illusion of containment, while Fen-Ma’s self-possession is invaded by the photographer’s lingering, desiring gaze. The boundaries between masculine and feminine are blurred in these images not only by Ma’s androgyny but also the inversion of the usual balance of power between (male) viewer and (female) viewed: Xing portrays Fen-Ma as the passive recipient of her active, penetrative gaze, rather than the other way around. Although Li spoke primarily about Xing, a parallel can be drawn here with Xiao Lu – both artists use photographic representations of performative acts to deconstruct and reclaim femininity as a category of being beyond patriarchal norms.

Xiao Lu, Tides (弄潮), 18 January 2019, Sydney, sand and, bamboo, inkjet print on silk; photograph by Jacquie Manning, commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art; photo: Kai Wasikowski, courtesy the artist.

Roundtable discussion

Li’s paper was followed by a screening of Xiao Lu’s Tides, a performance commissioned by 4A for Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of China/Avant-Garde and Xiao’s arrival in Australia. This meditative, haunting piece provided a much-needed opportunity to reflect on the ideas raised throughout the day in preparation for a dialogue between speakers and audience that concluded the proceedings.

John Clark opened the discussion by recalling McKenzie’s comparison of Xiao Lu with Marina Abramović as an illustration of the significant disparity in recognition and reputation faced by those Chinese artists who work against the conventional stereotypes of contemporary artistic expression. Although, as Roberts noted, Xiao is one of the few artists in China to maintain a consistent focus on performative expressions of the body—unlike other artists noted for their performance works, including Ma Liuming—she has enjoyed far less mainstream recognition and representation than Abramović, or even peers like Zhang Huan. Gladston offered another explanation for this disparity, pointing out that the almost complete lack of critical attention given to other aspects of Xiao’s artistic practice—her paintings, calligraphy and poetry, for example—reveals the issue as one of cultural translation. There is ‘a constant refraction [of aesthetics],’ he explained, ‘from one context to another’ and some forms of expression simply cannot be translated across different cultures. From this perspective, then, the very different levels of public recognition enjoyed by Xiao and Abramović can be understood as a product of unfamiliarity with Xiao’s points of reference and an inability to comprehend the context within which her work has been shaped.

A member of the audience then shifted the conversation by suggesting another comparative example: Ai Weiwei, the most notable exception to the rule of Chinese artists’ marginalisation within European and North American accounts of contemporary art. More specifically, they asked the speakers to discuss whether Xiao’s interrogation by state authorities in the wake of The Gunshot Event impacted her subsequent artistic practice to the same extent as Ai’s more recent interrogations and imprisonment have influenced his own work. Roberts was first to answer, noting that Xiao’s actions in 1989 were followed by a period of silence, absence from the public eye, and a considered management of any potential impact, though the cathartic force of the gunshot has remained a central inspiration within her practice, as shown by works like the self-referential photographic series 15 Shots (2003). Gladston reiterated his earlier observation that the interpretive speculation and critical discourse ignited by a work of art is often more powerful than the work itself, creating what Krischer termed ‘inter-generational conversations’ that ensure continued relevance despite changing circumstances. Xu and Jose agreed and noted the close, almost symbiotic relationship between the statements of artists and critics: a work becomes “dead” if no longer written about, while it is only through writing that a critic can experience a work from which they are separated by time or distance.

For Li and 4A Director Mikala Tai, this question of the relationship between art and textual documentation gained special relevance when applied to the inevitable translation of the performative into the photographic for storage in the archive. Li described this act of substitution as part of the “afterlife” of the work, another aspect of its encircling discursive existence, yet Tai recalled instances of artists she had commissioned to stage performance pieces in recent years who had forbidden any recording of their work to maintain its singular aura. Krischer, on the other hand, noted the parallel creation by other artists of performance (and installation) works that are deliberately “choreographed” with documentation in mind, while Gladston observed that much artistic production is now intended to be reproduced and circulated on a global scale.

Each of these points, as well as the many others raised during the day, found their reflection in the organisation of this workshop and accompanying exhibition. What better illustration could there be of the resonant “afterlife” of a work of art than this discussion of the context and implications of Xiao Lu’s decision to fire a gun into her own work, three decades after the sound of the shots and the smell of gunpowder have long since dissipated?

Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue 肖鲁:语嘿 was produced and presented by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 19 January – 24 March 2019. The exhibition and associated programming were supported by the Australian Government through the Australia-China Council of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellowship project led by Dr Claire Roberts Reconfiguring the World: China. Art. Agency. 1900s to Now (FT140100743), and the Faculty of Arts, School of Culture and Communication, The University of Melbourne. The China/Avant-garde Exhibition and Xiao Lu: 30 Years On was held at 4A on 1 February 2019.

About the contributor

Alex Burchmore recently received his PhD from the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University, where he now works as a sessional lecturer.