Balancing India: the story of Peter Nagy

Lleah Amy Smith

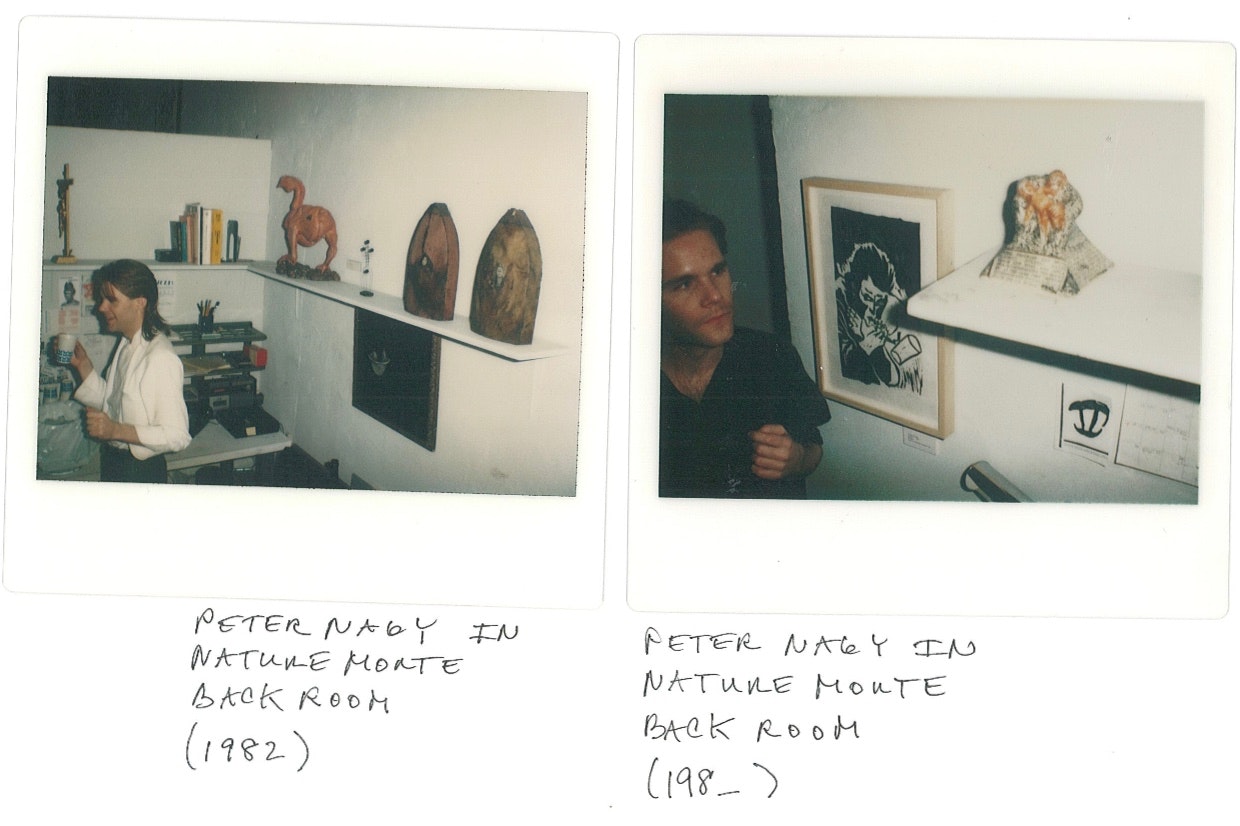

Polaroid courtesy Peter Nagy.

In 2012, University of New South Wales Art and Design lecturer and artist Gary Carsley handed me a text that dramatically transformed the way I understood and engaged with contemporary art in India. The essay, Acts of Delicate Balance, was written by Peter Nagy, a New Yorker who has called India home since 1992. The essay was part of a catalogue for an exhibition in Oslo, Norway, at the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in 2002, titled The Tree from the Seed: Contemporary Art from India, curated by Gavin Jantjes (1).

From New York to New Delhi

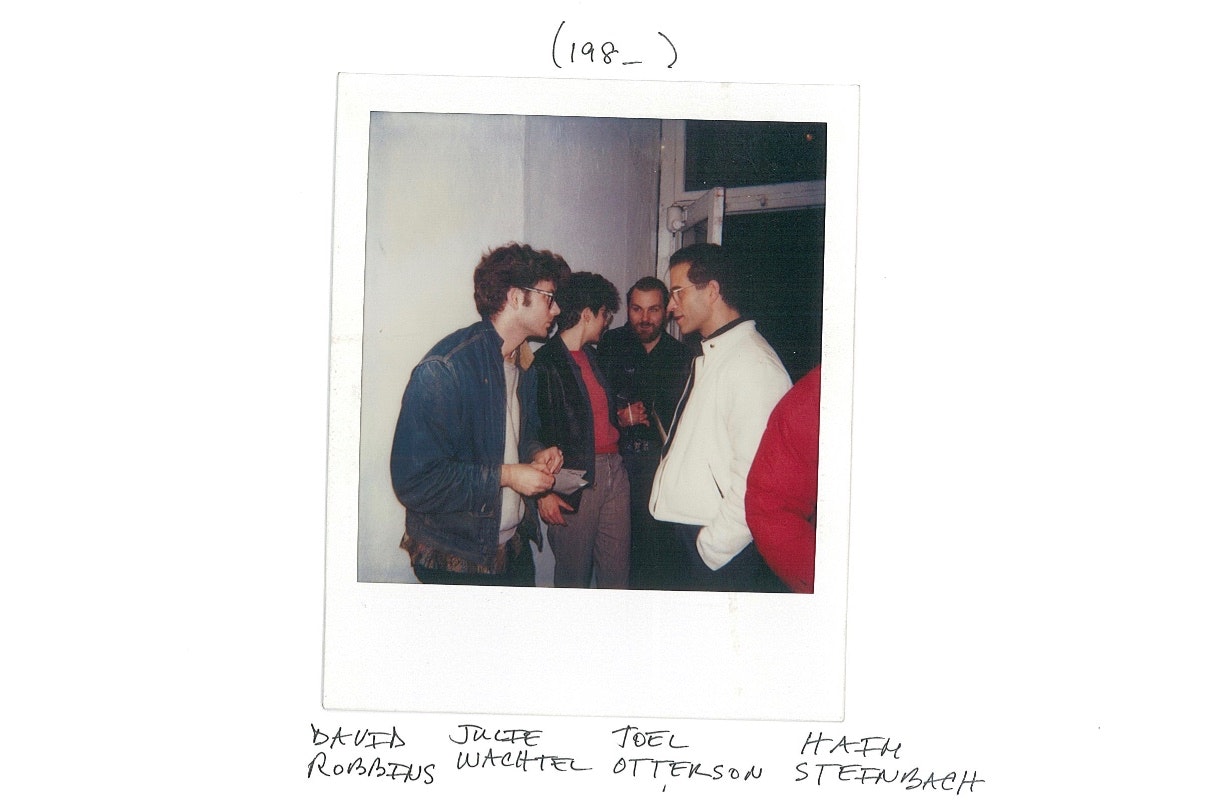

From 1982–1988 Peter Nagy ran gallery Nature Morte in New York’s East Village with former colleague Alan Belcher. The pair specialised in exhibiting the second wave of Pictures artists, a loosely affiliated generation of artists whose practices were informed by the crazed, media driven world. In the early days of the 1980s art scene in the East Village, Trisha Collins and Richard Milazzo, both curators, connected the young aspiring gallerists with SoHo’s Metro Pictures crowd, significantly informing the creative direction of Nature Morte. Nagy stated in an interview late last year, ‘I thought I would go into museum work because I was interested in the envelope that we create for artworks, the context that we build through galleries and museums that ultimately determines the value and meaning of artworks’ (2). Nature Morte positioned itself within the intellectual pocket of the East Village, a neighbourhood which rose to prominence in the early 1980s through graffiti and street culture and the kitsch/funk aesthetics championed by Grace Mansion Gallery, amongst others.

Throughout the 1980s, Nagy traveled across Europe and was fascinated by the Baroque and Rococo architecture and decorative arts from the mid-to-late 1980s he encountered. Nagy saw these moments in history as metaphors for the social psychology of the environments they were situated within, and also as parallels for the urban fabric of the cities.

In January 1989, Nagy visited Egypt with his gallery partner Alan for the first time and the experience significantly reshaped how Nagy envisioned his role in the art world. Nagy found similarities between the Baroque, Rococo and Decorative Arts of Europe in Islamic architecture and decorative arts, particularly within the architecture of the mosques and the carpets inside of them. Nagy has stated, ‘It [Egypt) blew my mind; I always say I was ready for the future, but I wasn’t ready for the past. I went completely nuts over Egypt, it was my first time in the developing world, and the Islamic world, and it changed my life completely’ (3). Nagy became infatuated with ancient Egypt and Islamic art and architecture and continued to travel abroad, discovering the Islamic cultures of Istanbul and Spain.

Born in 1959, Nagy always aspired to be a hippie, but was just a little too late. ‘I always had an attraction to India, because I was a child of the ‘60s. I wanted to be a hippie. I had Life magazine, I had the Indian block-printed bedspread, I had an orange and yellow shag carpet and I was burning sandalwood incense’ (4). Clearly inspired by Indian aesthetics and culture and interested in the Islamic arts, Nagy found himself in India for the first time in April and May of 1990. He reflects on this initial experience in India as a beautiful assault on the senses: ‘I remember getting to central Chowk in Jaipur, it was jam packed with traffic, there were two cows fucking in the middle of the Chowk, it was blazing hot and I cried; I thought to myself this is the greatest thing I have ever seen in my entire life. I had no idea I would spend the rest of my life here’ (5). Within a few months of returning to New York from India in 1990 the art market crashed and Nagy began rethinking the place he called home. ‘You can never be bored in New York, but it just wasn’t challenging anymore,’ he said (6).

In 1992, Nagy moved to India. He occupied a single bed in Noida, Uttar Pradesh, thirty-five kilometres from Delhi. Nagy paid for the room with his own paintings, bartered to Ranbir Singh, a collector living in Brussels but whose family lived in Noida. His residence had electricity about half of the time. Each day he painted and smoked hash—rinse and repeat. Despite the simplicity and the stark contrast to his life and his home in New York, Nagy felt a sense of freedom in India which was unachievable in New York: ‘There was nothing to eat in Noida,’ he laughed. ‘I would stand on my rooftop watching the markets being built, after the great wave of apartment blocks were erected overnight. There was no booze and no air conditioning. I would make paintings. I didn’t talk to anyone. I read a lot. There was only AM radio. On Wednesdays are 6 pm there was the Western music program [on the radio]. I would wait for songs such as Cindy Lauper’s Girls Just Wanna Have Fun. It was meagre, but at the same time it was a kind of a meditational retreat’ (7).

Years passed and Nagy remained in India. He spent eight months in Delhi and four months in Bridge Hampton, New York, for most of the ‘90s. The early years in India were spent reading and travelling on 400 rupees a day, he harboured a great desire to learn as much as he could about this new country and the only way to achieve this was to sink deep into her belly.

Ahead of Nagy’s return to India in 1992, collector Ranbir Singh wrote to the renowned Indian painter Bhupen Khakhar (1934–2003) and informed him of Peter’s arrival. Soon after, Peter sent his CV to Khakhar and was invited to participate in an ‘unofficial’ one-month residency at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. Khakhar also sat on the board of The Kanoria Centre for Arts, Ahmedabad, located on the CEPT University campus and invited Peter to be an official artist-in-residence. During this time, Nagy formed a friendship with Khakhar and was granted the privilege of delving through his archive of exhibition catalogues and mingling with Khakhar’s posse, artists such as, Nalini Malini, Rekha Roddwittya and the dancer Chandralekha, amongst others. These carefully sort after experiences left a significant impression on the young artist and curator and helped shape his understanding of a very foreign and complex landscape.

Nagy opened Nature Morte’s Delhi chapter in 1997, five years after moving to India. Nature Morte states it is both a commercial gallery and curatorial experiment; it has become synonymous in India with challenging and experimental forms of art; championing conceptual, lens-based, and installation genres and representing a generation of Indian artists who have gone on to international exposure. From 1997–2003, Nature Morte inhabited preexisting sites across India and hosted a wide array of exhibitions. From December 2003 onwards, Nature Morte has occupied a large, white, multi-level space in Neeti Bagh, Central South Delhi. Over the years it has provided an essential platform for progressive and experimental Indian artists to connect with the international art world and actively exhibited works by Indian artists alongside their international counterparts, such as Lynda Benglis (born 1941, USA), Lyndell Brown (born 1961, Australia) and Maurizio Vetrugno (born 1957, Italy).

Polaroids courtesy Peter Nagy.

The balancing act

I met with Nagy in Jaipur in December 2018 to reflect upon claims made in Acts of Delicate Balance and the current state of contemporary art and cultural production in India. The questions I posed to Nagy aimed to unveil whether contemporary art in India has progressed or regressed since 2002, the year his essay was published. The significant changes I have noticed since first visiting this country in 2011 have been monumental, yet they do not exist in isolation. Similar transformations can be seen across the world and largely in South Asia; there has been a rise in nationalism and right-wing politics, a greater divide between rich and poor, a rising middle-class with an increasing disposable income and many cases of violence fuelled by racial and religious hatred. In February 2019, as I write this text, India has reached its highest rate of unemployment since 2016. However, what these changes have also instigated is a nation that is looking inwards and looking South for answers for the first time perhaps ever, as opposed to the West and this is a significant and positive change for artists, institutions and society at large.

In Acts of Delicate Balance, Nagy’s principle claim is that art functions to the needs of a society. If everyday life is systematic and controlled, art offers a retreat from that system; if life is chaotic and unruly, art production is ordered and calm. Nagy considers art in India to function according to the later: ‘While one is virtually accosted by a profusion of material complexity on the street, engulfed with sensual stimuli of varying sorts, or surprised by random sightings of unusual behaviour … The experience of entering an art gallery is actually limiting and specifically about control. While life on the Indian street is seen to be “chaotic”, inside the gallery is necessarily thought to be “sane”’ (8). What is deemed ‘sane’, In Nagy’s sense, are works of art (largely paintings) tied to religion and the rural ideal which communicate ‘tangible connections with the art of the past and display technical proficiency and thematic continuity’ (9). Creative expression that sits outside of mainstream production is deemed ‘Avant Garde’, a term deemed relevant in 2002 and arguably still relevant today.

A visible shift away from creating work which is ‘safe’ and ‘controlled’ has taken place in India from approximately 2003 onwards; subsequently Nagy has been a great influencer in supporting works which challenge the notion that, ‘India is anti-podal to the West’ (10), and that strive for radicalism and utilise ‘references, materials, forms and subjects which have relevance to both contexts (the East and the West)’ (11). Yet, garnering appreciation of and support for cutting-edge contemporary art practices from the Indian public is challenging, largely because India is modernising at a rapid rate and over saturated with popular culture and other forms of mass-media.

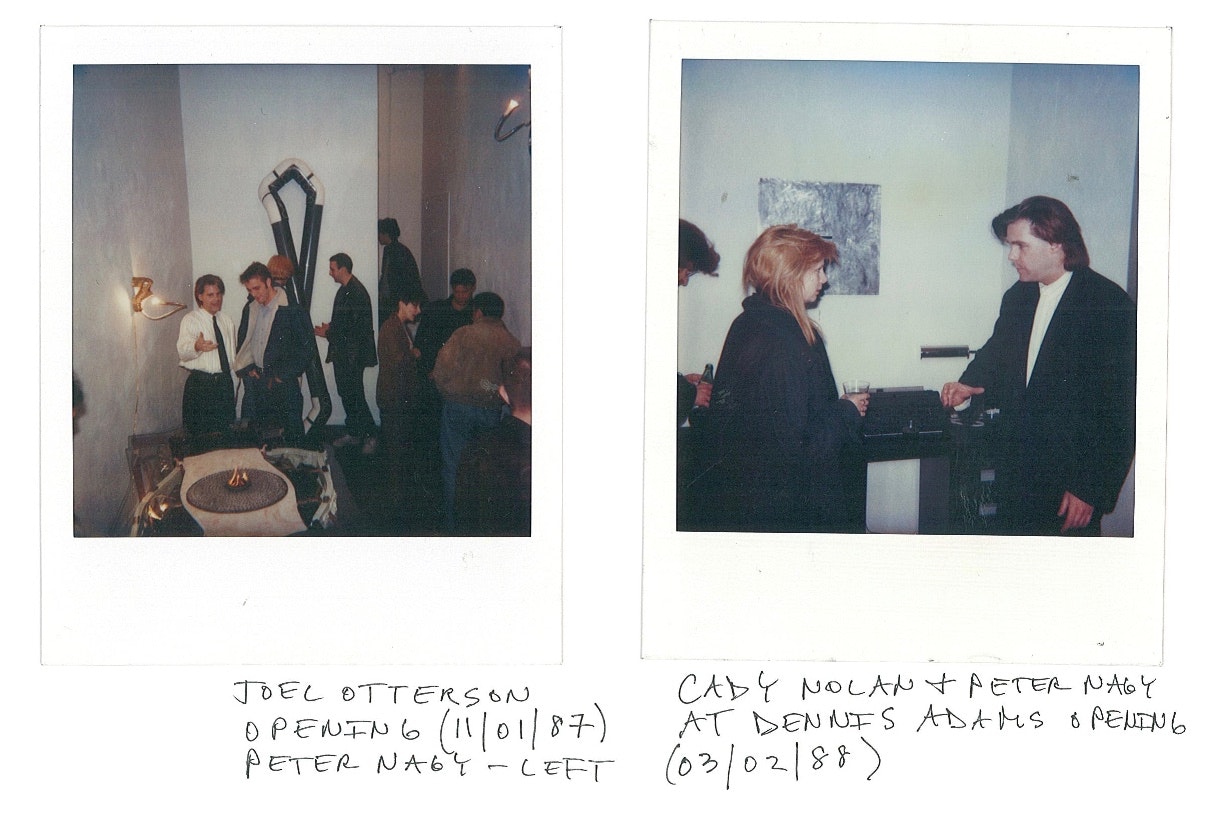

Polaroid courtesy Peter Nagy.

People feel that what is available on the phone is sufficient, that they don’t need additional cultural stimulus because they are absorbing a different kind of culture and the truth is they are overstimulated.

The series of questions I posed to Nagy when we met asked him to critically reflect upon Acts of Delicate Balance and to assess where change has taken place for better and for worse. I also asked Nagy to project his mind to the future and contemplate how India may function within the International world of contemporary art in years to come. Nagy was instrumental during 2000–2010 when the Indian market was burgeoning and Indian artists were receiving great interest from abroad. He was also there when the Global Financial Crisis hit and the market dissolved overnight. In the wake of such significant growth and decline, it is important to not only reflect upon the kind of work we see coming out of India, but also the social demands and desires of contemporary art and the role it plays in everyday life.

Nature Morte is a progressive and international platform for Indian contemporary artists, advocating for experimentation and supporting artists that challenge the notion of ‘India as antipodal to the West.’ Is this notion still relevant in 2019?

No, this is no longer relevant, I don’t believe Anita Dube feels the need to look to the West whilst curating the fourth edition of the Kochi Biennale. Luckily, over the past fifteen years, there has been a greater effort to look South as opposed to looking West. India feels more connected now to Asia, South America and Africa, much more so than it did seventeen years ago and that’s largely because of the internet. I can’t say we are seeing shows from these parts of the world, the international art shows are still largely coming from Europe, yet, we are having important conservations with our neighbours.

In Acts of Delicate Balance you comment that, ‘the differences between the roles played by contemporary art in the respective societies (India and the West) often appear to be at polar extremes,’ and further propose ‘this difference may revert to the needs of a society and what it desires from contemporary art.’ How have the needs of Indian society and what it desires from contemporary art changed over the past ten years (if at all)?

Indian society has been completely hypnotised by consumerism since 2002. The rise of the cell phone, mall culture and satellite television has completely revolutionised Indian culture. People feel as though they don’t need to go to museums and art galleries anymore because there are 108 channels on the television and ordering in a pizza is enough; this is a very new concept.

People feel that what is available on the phone is sufficient, that they don’t need additional cultural stimulus because they are absorbing a different kind of culture and the truth is they are overstimulated. People don’t want to be challenged, they are seeking something, which is easily consumable. If you want large audiences you need to have old master paintings and fashion-centric exhibitions.

I spoke with an Indian curator on Tuesday and she stated, ‘critical and conceptual art thinking is lacking in India because young people need to be taught to re-see their local environment.’ She claimed the ‘British education system reshaped what was considered art and who was considered the artist and has since hindered the ability to see the bustling markets and houses of worship as art.’ Do you agree with this view, or do you feel there is something else at play? Are the bustling markets and house of worship art?

I don’t think so. India at large does not need contemporary art to be challenging, because life at large is already challenging enough. It is the reverse in the West; they want to be challenged by contemporary art because they don’t feel challenged enough within their daily lives.

But what about the aesthetics of everyday life? Like the fusion of the old and the new in Jaipur, with the stark architectural geometry of historical and contemporary buildings and the beautiful ornate surface treatments. An outsider may see these as art works, they aren’t particularly complicated or challenging, but they are found outside of the gallery/museum and the gesture itself could be an art.

Yes, it is an aesthetic gesture and Indians are doing it as an aesthetic gesture, but then you need to ask where is the place of aesthetics.

But do you think the general public see these actions as carefully constructed aesthetics or just part of the everyday?

Because they have grown up with it yes, they may take it for granted, but it is still an aesthetic gesture. So much of the rituals in the temples are highly aesthetic gestures, but it’s in a temple not in a museum.

No one goes to church in the West anymore, and in the West religion has been purged of esotericism. I was raised an Episcopalian and there was no esotericism in the religious practice at all. Going to church was a social function; you went to the ceremony, the kids were placed in daycare and the mothers went to have coffee, there was nothing mystical about it at all. But I remember the first time I went to a Roman Catholic ceremony, I noticed it was in Latin and there was incense, it felt like going to India, but I was in New York, it was so exotic—the Roman Catholic Church preserved mysticism.

On a psychic level, humans need mysticism in their lives, in their brains and their equivalences. If you’re not getting it from religion, you need to get it from somewhere. Western society celebrates the artist who gives that to them, a society celebrates what it needs at the time. There is always a social craving for a certain type of experience, when they find an artist facilitating that, they encourage and promote them.

You mention the gallery experience is limiting and controlling in India. I find the term ‘control’ an interesting term. Do you think control is actively challenged by contemporary Indian galleries in any way?

The gallery is the antithesis to daily life. I learnt this from older Indian artists who said they didn’t want the politics, the chaos and the mess of the street to enter the gallery, they wanted the Western white box, they fought for it and they got it.

Do you think there is still a need to categorise artists by geography and nationality?

I wrote this essay for an Indian show in Oslo, therefore at that time it was relevant. However, artists like Dayanita Singh, Subodh Gupta and Anita Dube are now at a point in their careers where they can refuse to be categorised in such a way. Yet, the culture and environment that you are born and raised in is relevant to your practice whether you want to admit it or not. We are now also seeing a rise in the importance of the hybrid artist, curator and gallerist, a person like myself who is born and raised in one culture and then transplants themselves into another culture and that is interesting.

You state, ‘India represents a successful synthesis of diversity into one amalgamated culture.’ Do you think the amalgamated cultural identity of India has been disrupted given the social and political climate of today?

India is as big and diverse as all of Europe. The differences between Kashmir in the North and Kerala in the South are as great as the differences between Finland and Sicily. I am amazed by how peaceful it is in this country. It has certainly become far more violent in the past 26 years I have lived here, but again they say that perhaps it’s not more rapes happening it’s just that more rapes are being reported. I believe the violence is partly a result of absorbing American media, but at the same time I am amazed, you would think this country would be burning up, with all the schisms, problems, inequalities and with the current government problem, but it isn’t, it exists with tolerance for the other.

We at the gallery incur absolutely no censorship. The gallery is a very small and private place, but still, by and large we are free. However, there has been once instance, at the first edition of the Sculpture Park, Jaipur, 2017 we had a series of bronzes by Mrinalini Mukherjee and one was called Shivling, 2014 (a reference to Hindi God Lord Shiva) and we did have right-wing Hindu goons show up after the opening and cause problems. We believe they were tipped off by guards. They turned up with media and press and they went right to that artwork and we had to take it out of the exhibition. They said if we didn’t they would destroy the show. We were taken back by this because it was simply about the title of the work, it had nothing to do with the artwork itself. We do have to be conscious of these things, but India is resilient and there is harmony amid the chaos.

You conclude Acts of Delicate Balance by reinstating your ambition for equilibrium that is shared by all societies, and posit the beginning of a single, globalised society which is striving for its own equilibrium. Do you think we are closer or further from this ideal than we were when you published the essay 17 years ago?

Further away, everything has just gotten worse and worse. It is a disaster now. Everyone is terrified of the other—it is just a mess.

Polaroids courtesy Peter Nagy.

During our conversation, Nagy openly expressed his frustration at the current state of the Indian contemporary art world, a frustration felt not only by him, but also his counterparts, artists, gallerists and curators: ‘Everyone in the Indian contemporary art world is frustrated, they’re pissed off they don’t have more opportunities here and collectors here’.

It is not for a lack of trying. Throughout 2000–2010, when the Indian market was bustling with interest, formative spaces such as Khoj International Artists Association, Kiran Nadar Museum of Art and the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum provided significant platforms for various types of practices to be showcased on an International platform for local and international audiences; yet, Nagy communicated that the weakest link is the galleries, with cutting-edge spaces such as Gallery Maskara, Mumbai closing its doors in 2016 and Lakeeren Gallery following suit in 2017. The market and the audience just isn’t large enough to support and maintain experimentation within contemporary practice and artists unfortunately fall victim to the market, creating works, which Nagy earlier coined as the pious religious image and the rural ideal (12).

Since 2002, the situation in India has changed dramatically. The nation has become increasingly open and for better or worse is absorbing Western culture at a rapid rate. Indian artists are securing opportunities in Europe, America and Australasia and Asia, whilst also conscientiously working towards establishing new networks and lines of communication with South America and Africa. Khoj, for example, recently undertook the Coriolis Effect project (2015–2017) that focused specifically on activating the social, economic and cultural relationship and historical exchange between India and Africa.

Yet, what appears to be unchanged is the response from Indian audiences and what they hope for and expect out of contemporary art. Of course, it is understandable that a society dealing with alarming rates of pollution, traffic congestion, unemployment and poverty seeks an art that is simple, idealistic and easy to digest. Unfortunately, however, despite not having the capacity to deal with the realities and tensions of contemporary life, there is a need for art to infiltrate and encourage the sharing of knowledge, and information, to provide a space for conversation and perhaps idealism in a different way; where people discuss the troubles and conditions of the contemporary day and actively seek to find solutions together for a better tomorrow.

Notes

(1) Gavin Jantjes (ed.), The Tree from the Seed (Oslo: Heine Onstad Centre, 2002).

(2) In person Interview by author, Jaipur, 6 December 2018.

(3) ibid.

(4) ibid.

(5) ibid.

(6) ibid.

(7) Peter Nagy, ‘Acts of Delicate Balance,’ in The Tree from the Seed, 3.

(8) ibid.

(9) ibid.

(10) ibid, 4.

(11) ibid.

(12) ibid.

About the contributor

Lleah Amy Smith has lived and worked across India and Australia since 2011. She returned to Sydney in May 2017 after living and working in Delhi consecutively for two and a half years.