Special beings: Yasumasa Morimura and Dumb Type in Metz

Judy Annear

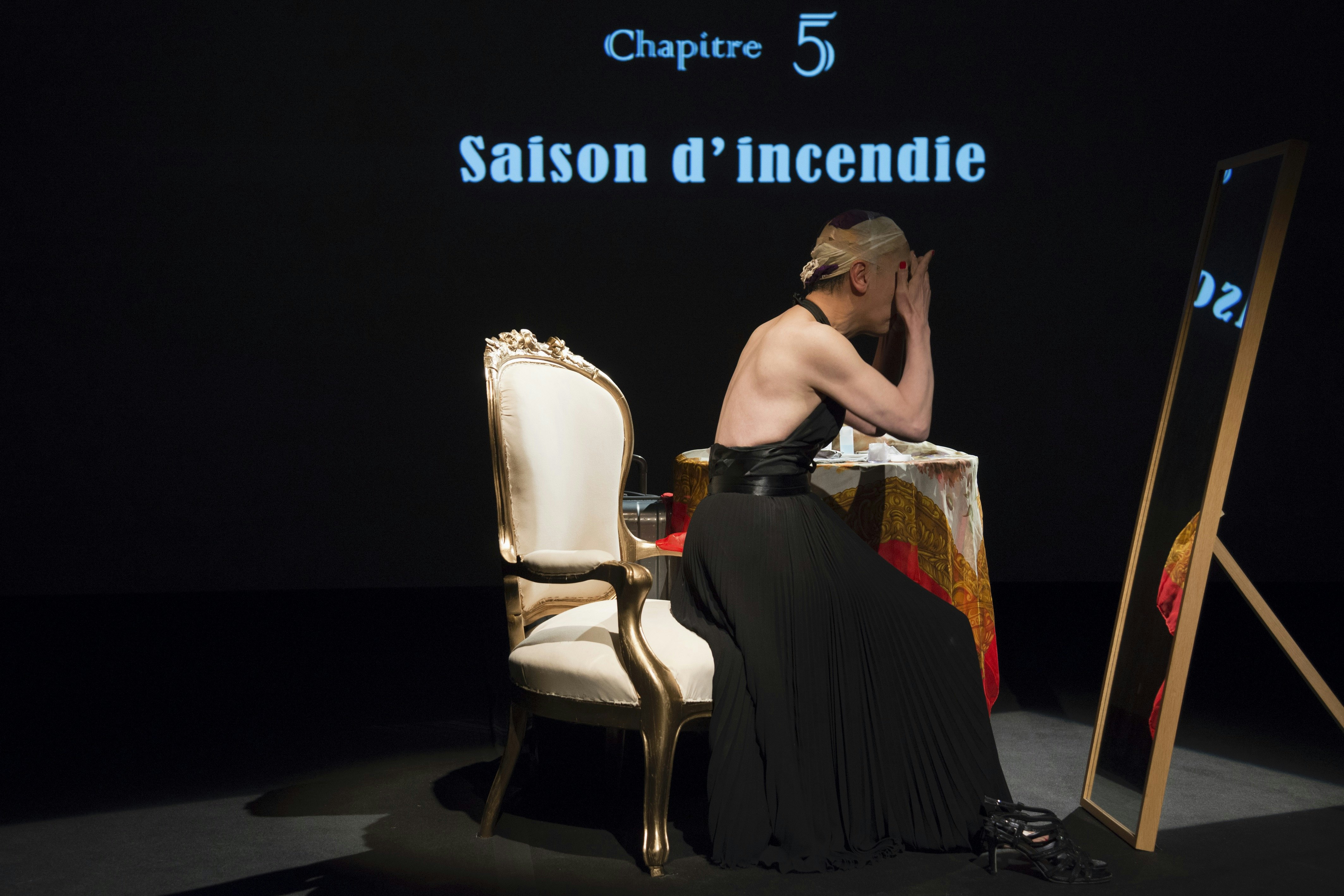

Yasumasa Morimura, Nippon Cha Cha Cha performance at Centre-Pompidou Metz, 24 February 2018; photo: Jacqueline Trichard, Centre Pompidou-Metz.

I

On 24 February 2018, 150 years after the restoration of imperial rule in Japan and 160 years after Japan was forced to sign trade deals with various western powers, artist Yasumasa Morimura performed Nippon Cha Cha Cha at Centre Pompidou-Metz. This 75-minute work is a reflection on his own history and art practice growing up in a country dominated by the complexity of its past transitions. These transitions have ranged, since 1868, from the feudal to imperialist and militarist, then swiftly to a democracy engineered by the United States of America after World War II. Invoking writers such as Roland Barthes, Yukio Mishima and Norman Bryson, Morimura focusses initially on Barthes and his book L’empire des signes (1970) (1). The French semiotician made three visits to Japan during 1966 and 1967 (2), and Morimura plays with Barthes’ idea of ‘emptiness’ in relation to Japanese culture. Paraphrasing Barthes, Morimura notes ironically that ‘what is at the centre of Japanese culture is neither an essence nor a truth but a void; further, this Japanese vacuum can coat any suit … values, thoughts, can be worn and removed like clothes.’ (3).

Barthes was writing, wittingly or not, about his own inability to understand what he was observing; the emptiness (vide) is the space between himself and the other (the object of his deep fascination), rather than emptiness residing in that other itself. Barthes noted the obverse of western displays of power in relation to the Japanese emperor, and the ambiguities of men playing female roles in traditional Japanese theatre. He saw such actors as combining the signs of woman as translation rather than, as in the west at that time, transgression (4). Morimura seizes on Barthes’ idea of the void, using the actual ‘emptiness’ of a full-length mirror in his work to create, frame and reflect forms, turning them toward to the audience. These forms, or ‘special beings’, are insubstantial and constantly renewing aspects of an image (5). If the mirror can be a metaphor for the void, then the shifting phantoms on the mirror and their relationship to the real are what Morimura manipulates with consummate skill. The clothes and makeup he applies and discards, his shifts in gender and culture, often occur in silence. Yet, at moments in Nippon Cha Cha Cha, Morimura screams—an inarticulate catharsis is all that is left when language, history and time fail.

Yasumasa Morimura, Nippon Cha Cha Cha performance at Centre-Pompidou Metz, 24 February 2018; photo: Jacqueline Trichard, Centre Pompidou-Metz.

Yasumasa Morimura, Nippon Cha Cha Cha performance at Centre-Pompidou Metz, 24 February 2018; photo: Jacqueline Trichard, Centre Pompidou-Metz.

A 1995 essay by art historian Norman Bryson on Morimura’s restaging of Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) as Portrait (Futago)(1988) (6) informs a sequence of Nippon Cha Cha Cha. Now, Morimura restages Olympia but as Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Morimura is in his 60s and his nude Madama Butterfly is an aging diva—further, the ‘maid’ has become a man in a stovepipe hat directly paying court. This play between race, gender, popular and high culture, trade, history and what monocultures may claim as their own is indicative of Morimura’s work from his first self-portrait in 1985 onwards. Bryson writes:

‘… Morimura’s tableaux say that transnational flows of money, information, and technology have dismantled essentialism’s basic ground. The program of post-national, post-gendered, de-essentialised identity has already been put in place. But not by cultural critics—by capital itself.’ (7)

Marilyn Monroe/Morimura appears, initially in her white dress with its billowing skirt, displaying herself to university students in a Japanese classroom, and then in black with a dildo under that skirt. The American icon of post-war femininity ‘penetrates’ then segues into novelist Yukio Mishima, and a variation on Mishima’s ultra-nationalist speech made before he committed ritual suicide in 1970. Morimura’s variation on that speech insists on the recognition of artists and their practice, and against the empty face of capitalist co-option. Morimura takes off his suit as Mishima and becomes ‘himself’. And yet, who is Morimura? Who are the characters he has inhabited, and why? The history of Morimura the artist is that of the child of a post-war marriage between Japan and America—General MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito are his fathers.

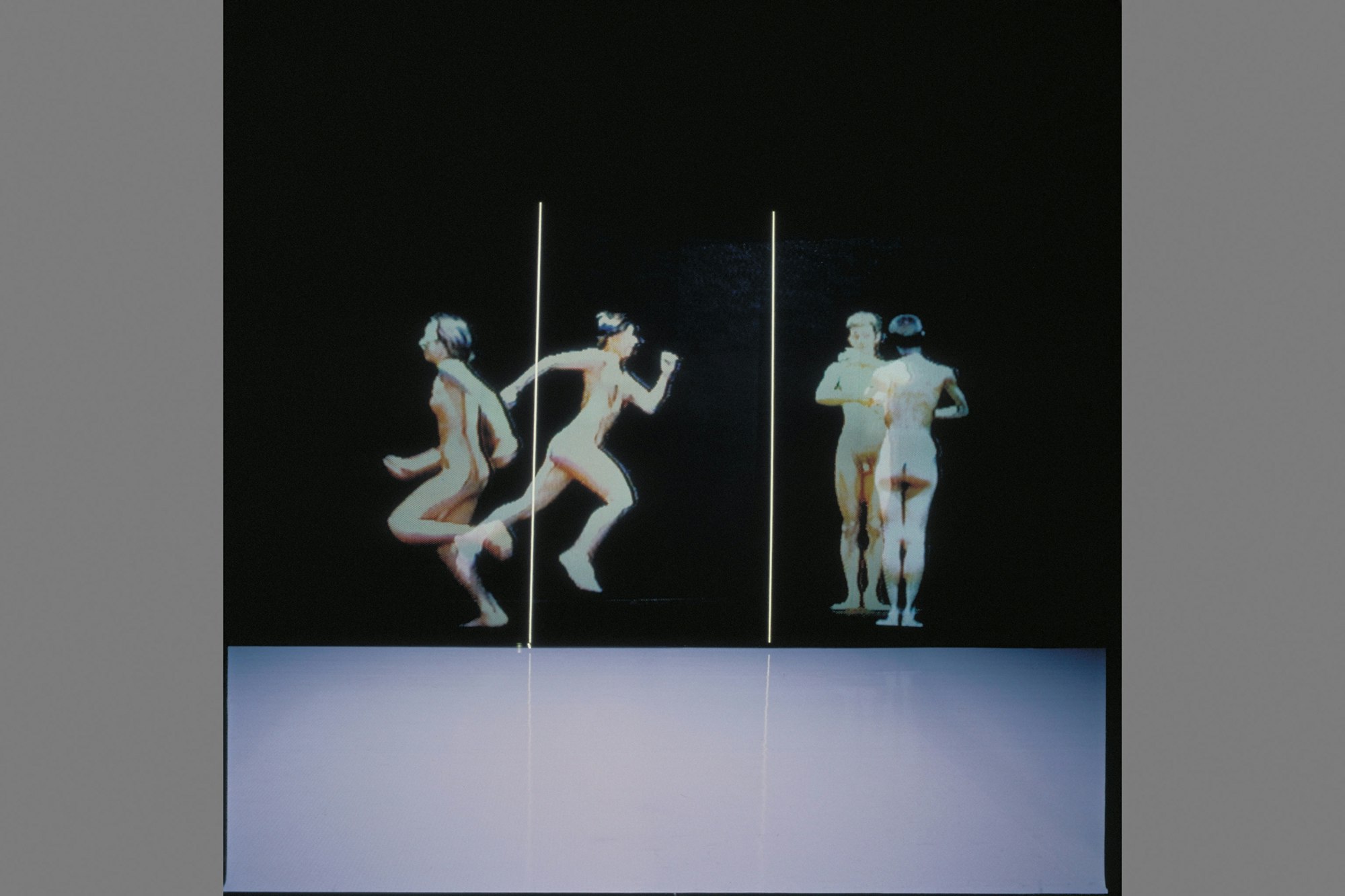

Dumb Type, Pleasure Life, 1988, performance; photo: Kazuo Fukunaga.

II

Nippon Cha Cha Cha was one of ‘10 evenings’ programmed at Centre Pompidou-Metz in conjunction with the encyclopaedic exhibition Japanorama: A New Vision on Art Since 1970. The thankless task of a national survey—of something, anything—is perhaps the most diabolical undertaking for any exhibition curator or book editor; it is fundamentally impossible to mirror critically the many and various nuances of cultural forms and their complex connections to each other, their makers and audiences. This is especially the case when the audience has only been exposed to bits here and there, whether historical or contemporary. The variety of forms and ideas available to the curator or editor in such undertakings makes decisions partial, yet a view has formed over more than 150 years, in this case between Japan and France. That view grasps at the relationship between two very particular cultures who are prolific in highly stylised activities and between them could be said to have made possible what is known as western modernism.

Japan and France have been entwined culturally since 1868. The avalanche of manners and meanings went both ways: Impressionism, Japonisme, Art Nouveau, traditional architectures, modern design, experimental dance, Hokusai, manga, anime, Comme des Garçons, sushi, Hello Kitty, classic French food—the list is a long and diverse one. Where to start with a survey of recent art, what to include, and why? Yuko Hasegawa, artistic director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, has a long history of curating contemporary Japanese and international art. She has collaborated extensively with architects, and is more than familiar with large complex projects. For Japanorama, Hasegawa takes her starting point as Expo 70 in Osaka. By 1970, Japan had largely rebuilt from the effects of a devastating war and was moving toward the ‘bubble economy’ and international status as a producer of highly refined design and fashion. In the following decade, in 1986, the Centre Pompidou presented the encyclopaedic exhibition Japon des Avant Gardes 1910-70. Encompassing visual arts, cinema, literature, music, design and architecture, this exhibition was organised chronologically according to key avant-garde movements in Japan pre- and post-war. Conceptually, the exhibition Japon des Avant Gardes moved away from the fascination with the actions of traditional Japanese culture on the west, and correspondingly western culture on Japan, and focused instead on modern and contemporary Japanese artists. Centre Pompidou had already looked at the relationships between Paris and key European cities, as well as New York, but this was the first time France looked in this way at Japan.

Half a century later, Japanorama appeared at Centre Pompidou-Metz, 330 kilometres east of Paris. While overlapping about 20 artists with Japon des Avant Gardes (On Kawara, Genpei Akasegawa, Yoko Ono, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe, Yayoi Kusama, Lee Ufan, Kazuo Ohno, Kishio Suga, Atsuko Tanaka, Tadanori Yokoo, et. al.), any resemblance between the two exhibitions ends there. Japanorama showcased works by 104 artists and collectives that were presented thematically rather than chronologically; correspondingly, the placement of works engendered a very open installation as works and ideas flowed into each other. SANAA Tokyo designed the structure of this exhibition and took the Japanese archipelago as a model. Yasumasa Morimura and the Kyoto-based artist collective Dumb Type were included within the main body of Japanorama. Dumb Type had an entire separate floor of installations at Metz (continuing beyond the exhibition’s close to 14 May), with some individual members and related artists appearing in the performance ‘evenings’.

Dumb Type, Lovers (1994), installation; photo: ARTLAB, Canon Inc.

The dynamic nature of Dumb Type, where dancers, artists, musicians, scientists and philosophers came together at Kyoto City University of Arts in the 1980s to work collaboratively, was presented by Hasegawa in Japanorama through various installations related to performance works such as Pleasure Life (1988), pH (1990), and S/N (1994). Other installations, for example MOV (2014), compiled material from works such as Or (1997), memorandum (1999) and Voyage (2002). Archival documentation was also presented. As an introduction to the scope of Dumb Type’s inventive performance and installation work over a 30-year period this was a useful if tangential attempt. Individual works by Ryoji Ikeda, Shiro Takatani and Teiji Furuhashi sat alongside collaborative pieces; Norico Sunayama’s solo performance work appeared as one of the ‘evenings’. Furuhashi’s Lovers (1994) was the only solo piece he constructed before his untimely death the following year. The pared back installation of Lovers includes a tower of slide and video projectors in the centre of a dark room where nude figures of Furuhashi and his friends appear to run along the walls, overlapping with each other yet never actually embracing. Vertical red lines seen with the figures have two words: ‘Fear’, ‘Limit’.

Though no Dumb Type performances were represented live at Metz, traces were evident in the exhibition’s installations through repetition of various motifs such as the sounds of a heartbeat or medical equipment, the red crosshairs of a target, and Dumb Type’s singular collaging of sound, music and voice. This was most effective in Playback (1989/2018), which took its original inspiration from Pleasure Life. Playback is a grid of stands, topped by turntables emitting various sounds apparently at random. Humans may try to find sense in the elegant structures and distorted communications but find themselves embedded in a closed circuit (8).

Repetition of movement has been an important part of Dumb Type performances throughout their practice, in combination with specific forms of light, sound and machine activity. The use of grids and data appeared in their work very early and while the dance forms and bodily expressions they used could recall the apparently pointless yet deeply poignant repetitions of Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, Dumb Type always put the human body into action with the machine. While the technologies they used in their first decade of work can now appear antique (for example, slide projectors, 16 mm film, punch cards, and turntables), they were and remain at the forefront of adapting digital technologies in various critical ways to their art practices. As with the performances of Yasumasa Morimura, Dumb Type have used personas, masks, and called attention to the overlooked. In the early 1990s they were the most political artists in Japan with their attention to minorities and to the AIDS crisis (9).

The works of individual members of Dumb Type have segued into less overtly critical reflections of contemporary life—for example, the data sublime of Ryoji Ikeda and the depthless video panoramas of Shiro Takatani. However, the installation at Metz of flashing neon words from S/N (Love/Sex/Death/Money/Life) are a reminder of the capitalist unification of all forms of desire. The drifting geographies of Voyage recall the possibilities and elusiveness of proximity as well as the thirst for exploration and its dark side—exploitation. These were always undercurrents in Dumb Type’s work. While a number of mainly younger artists included in Japanorama such as Chim Î Pom, Naoko Hatakeyama, Lieko Shiga, Atelier Bow-Wow and Home-For-All questioned the post-Fukushima reality of modern Japan, Dumb Type and Yasumasa Morimura point to the ongoing fallacy yet terrible necessity of art as socio-political critique.

Notes

The author wishes to thank University of New South Wales Art & Design, Sydney; Centre Pompidou-Metz; Dumb Type, Kyoto and Yoshiko Isshiki Office, Tokyo for facilitating this essay.

(1) Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1982).

(2) Barthes visited between the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the 1970 Osaka Expo. These two events are generally considered to signal Japan’s re-entry onto the world stage after World War II.

(3) Nippon Cha Cha Cha program notes, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2018, np [accessed by author 24 February 2018].

(4) Empire of Signs, op. cit., pp. 53, 91.

(5) See Giorgio Agamben, ‘Special being’, Profanations, trans. Jeff Fort (New York: Zone Books, 2007) 55–60.

(6) Norman Bryson, ‘Morimura: 3 readings’, Art + Text 52 (1995): 74–79. Futago is Japanese for ‘twin’.

(7) ibid, p. 77.

(8) Yukiko Shikata, ‘Space as “image-machine”’ in Minoru Hatanaka, Akira Takada and Shunichi Shiba (eds.), Dumb Type: Voyages (Tokyo: NTT InterCommunication Center, 2002), 31.

(9) For various perspectives on Dumb Type’s use of technologies, the body, the roles of the women performers, and relationship to other forms of theatre, see Peter Eckersall, Edward Scheer and Fujii Shintaro (eds.), The Dumb Type Reader (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculum Press, 2017).

About the contributor

Judy Annear is a writer, curator and adjunct at the University of New South Wales, Sydney.