Wait man kam (White man is coming)

Eric Bridgeman

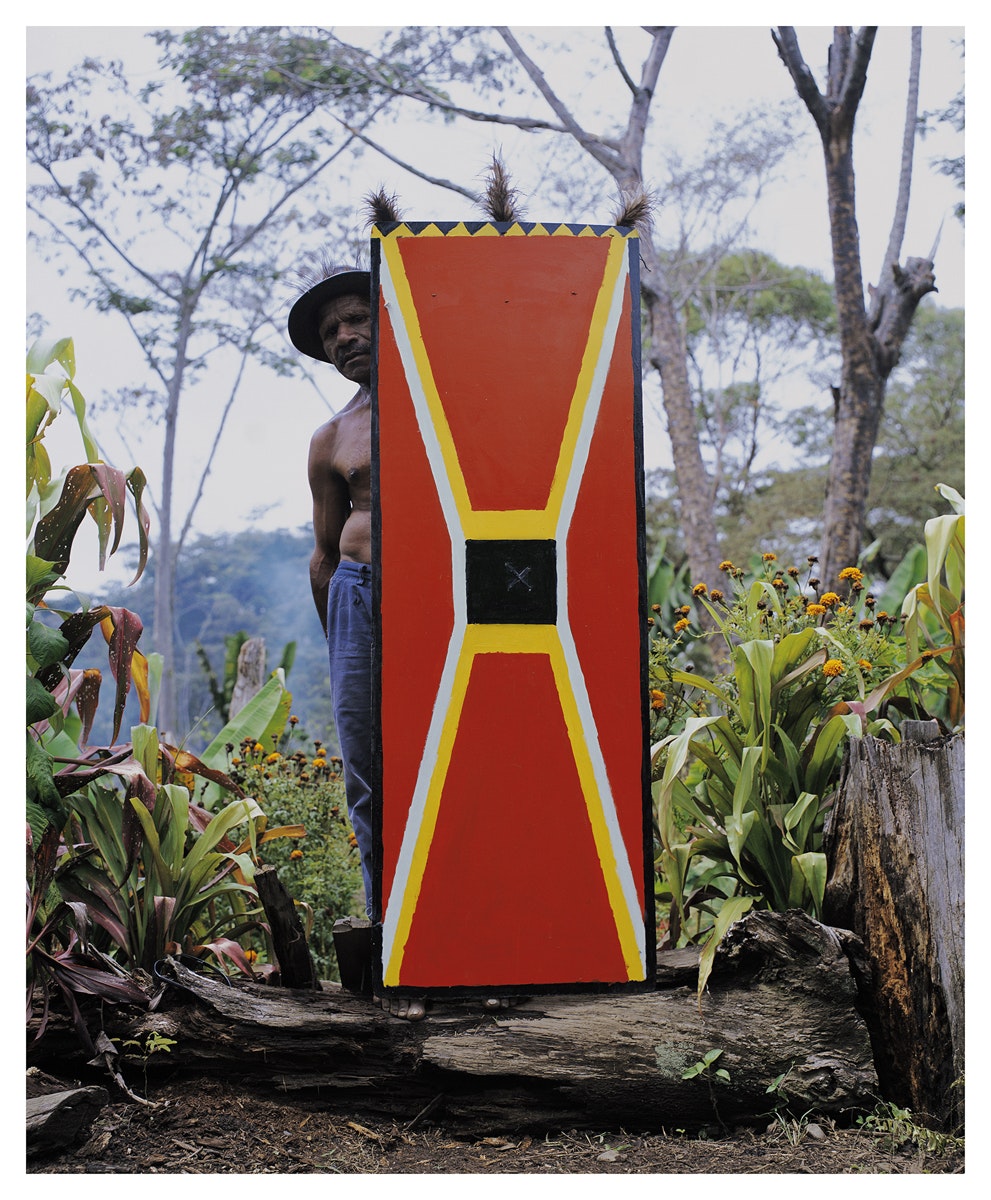

Isaiah with kuman at Wahgi River, Kudjip/Banz, Jiwaka Province, Papua New Guinea, 2017; photo: Eric Bridgeman, courtesy the artist.

My name is Yuriyal Awari Muka. I am the son of Raymond George Bridgeman, descendent of English convict and Australian Joe Bridgeman, and Veronika Gikope Muka, daughter of Muka Alai of the Yuri Alaiku clan, Omdara, Simbu Province, Papua New Guinea. I grew up in the contested land of Australia, and down under I respond to the Anglo-Saxon name Eric Bridgeman.

Aside from my cultural identity, I am an artist. I use a range of materials to produce photographic portraits, performances, designs, multimedia video and sculptural installation between my homes in Australia and PNG. Over the past decade I have been spending time living, making and cruising up and down and around the Okuk ‘Highlands’ Highway in PNG. After my second visit as an adult in 2009, my family invited me back and offered to build me a house. In the years that followed, I became entrenched within the community in Kudjip, Jiwaka Province, comprising of Yuri Alaiku hauslain (relatives) from Simbu, many tambu (in-law) and local papa graun (custodial land owners). I began creating multimedia work in partnership with family members as a point of personal exchange. My role as Yuriyal (Man of the Yuri), community member, art maker, producer and messenger emerged through times of hamimas (happiness), hevi (trouble), lewa (love), longlong sikarap (illness), taim no gut (death), singsing (celebration) and planti samting bagarap (politics).

The following portraits, photographic documentation and expanded captions have been made available to provide a point of access into the developmental stages of our kuman (shield) workshop, describe the environmental and political context for my experiences and, to state plainly in ‘broken’ Tok Pisin, wokim stori gut (tell the story well).

Martin Kirua with ‘323’ Kuman, Okuk Highway/Kudjip bus stop, Jiwaka Province, Papua New Guinea, 2017.

Kudjip is located forty-five minutes by PMV (Private Motor Vehicle) east of Mount Hagen along the Okuk (Highlands) Highway. Situated comfortably within the Wahgi Valley region of the newly founded Jiwaka Province of Papua New Guinea, the community is a melting pot of cultures and alliances. The Nazarene Hospital, operating in Kudjip since 1967, draws in patients and visitors from across the region; the Carpenters Tea plantation has attracted generations of migrant workers from neighbouring provinces and, like my family from Simbu Province, many arrived in Kudjip after fleeing areas struggling to control decades of tribal conflict. The Kudjip bus stop sees many people come and go, direct to Hagen or Kagamuga Airport, Banz, Minj, Kundiawa, Goroka, as well as the infamous light to light (overnight) buses to Lae and Madang.

Mote Kirua in front of Bengan Haus Man, Kudjip, Jiwaka Province, Papua New Guinea, 2017; photo: Eric Bridgeman, courtesy the artist.

Bubu Mote Kirua is the father of Moses Mote, my most trusted cousin and caretaker of my house in Kudjip. Mote is a constant presence and, whether he is slowly weaving pig-rope for sale or telling elaborate stories of tumbuna (old) times, he makes us feel safe despite his frailty and escalating senility. He gives us strength through his passionate telling of anecdotes—we marvel at the fact that he is still with us and has survived it all. In conversation, I would sometimes mention to Mote how people in the Western world treat and house the elderly, which is always met with amazement by him and others. In Papua New Guinea, the bubus and the elderly are the glue of each household.

Moses constructed this kunai raun haus (grass hut) for me in 2015 with the help of a number of local relatives. I witnessed the building process—not documenting or filming it is one of my small regrets. Moses copped a lot of slack from others for building a house that they said would remain empty, believing I wouldn’t return. He knew that I would and, more importantly, understood my intentions for the structure. This house would not only be my sleeping quarters, but a chance to realise my ambitions of creating a working studio space in Papua New Guinea.

I would sometimes mention to Mote how people in the Western world treat and house the elderly, which is always met with amazement by him and others. In Papua New Guinea, the bubus and the elderly are the glue of each household.

Interior of Bengan Haus Man, Kudjip, Jiwaka Province, Papua New Guinea, 2017. Photo: Eric Bridgeman. Courtesy the artist.

I first slept in the round house in March 2017. It was incredibly bare, but I enjoyed the space and the colours of the timber and woven blinds for at least a few weeks before I decided to make any changes. There was so much political activity going on in the run up to the general election that was conducted between 24 June and 8 July, in addition to personal family drama, that I became depressed and scared to make any bold moves— this house was my sanctuary from the heaviness outside. However, it didn’t feel right using this space on my own. I endeavoured to invite the boys, the uncles—my wan skots—in, and for the remainder of my time there it would be our space.

I first consulted with Mori Kaupa, village elder, about working on a kuman project in the house with a number of young men and uncles. At our first meeting he had gathered around thirty participants. We spoke about shield designs specific to our Yuri Alaiku clan heritage and set about creating upward of twenty personalised kuman. The sessions were part teaching, discussion and application. Each individual was tasked with drawing and colouring three designs each, after which we would compare and discuss before finally selecting the design favoured by the group. Time constraints and logistical issues saw us abandon the option of using traditional timber, in favour of the readily available and lightweight plywood. This distinction between materials suggested that we were no longer concerned about replicating the kuman as a defensive weapon loaded with violent histories; we were now in the business of kuman paintings.

Before long, the house was full. It became a club house, or Haus Man, and was bursting with creativity. The house provided, at a critical time during the election, an escape from the politics spreading through the villages, as well as an opportunity for the group to come together and consolidate their support or voting alliances. Mori Kaupa began by instructing the younger men, many of whom had no experience or knowledge of shield designs, on the foundational attributes belonging to a traditional Yuri kuman. The key to the success of their design was the personal and unique insignia or geometric strength.

Over three weeks we met at my house in large and small groups, depending on availability. The looming election made it increasingly difficult to schedule everyone at the same time. Although the house was an open space, I grew to appreciate the strain the men were under. Some were attending school during the week, most went to church on Sunday, some were breadwinners while most had household and gardening duties. It was hard to convince them that what we were doing was more important than these daily duties and family responsibilities, so I didn’t, because it wasn’t. Once we began marking the boards with paint, I took my hands off the wheel and let the process unfold. I could sense something was brewing in the town though, as I watched small groups gathering to discuss political strategies. It happened that one afternoon, my Uncle Maus Wara called for the group’s attention, stating his and others’ intentions to leave the next day for the village in Simbu to oversee the handing out of cash by then incumbent Member for Gumine Province, Nick Kuman. I was upset that my uncles were attempting to persuade the younger men to leave through bullying tactics. Some of the best painters left the next day, but we carried on. I felt this conflict presented a major question typical in the lives of men in modern Papua New Guinea: am I an individual, or am I the tribe?

Mori Kaupa with kuman, 2017; photo: Eric Bridgeman, courtesy the artist.

Our work began to take form when the first kuman paintings were placed leaning up against the interior wall. Apart from photographing the completed work, we had no solid plans for the next move. A healthy discussion followed; everyone was now critically engaged in how to effectively present the work, in portraits, performances, video or public interventions. Many ideas were put forward, some were ambitious, and some required an appreciation of the political climate rising outside, such as dramatised fight scenes in the public square. All of these options had practical and cultural barriers, so we voted to proceed with the seemingly simple task of individual portraits and allow the experimental nature of the work lead us forward.

I felt this conflict presented a major question typical in the lives of men in modern Papua New Guinea: am I an individual, or am I the tribe?

Our work began to take form when the first kuman paintings were placed leaning up against the interior wall. Apart from photographing the completed work, we had no solid plans for the next move. A healthy discussion followed; everyone was now critically engaged in how to effectively present the work, in portraits, performances, video or public interventions. Many ideas were put forward, some were ambitious, and some required an appreciation of the political climate rising outside, such as dramatised fight scenes in the public square. All of these options had practical and cultural barriers, so we voted to proceed with the seemingly simple task of individual portraits and allow the experimental nature of the work lead us forward.

We congregated at Mori Kaupa’s house in Block 4A, a section between the Carpenters Teas Plantation and the Wahgi River. This was the first time the work had been taken out of the house and into the public realm and we were ready to take portraits of each individual with his shield. There was a lot of deliberation over choosing a location for the shoots. I reminded everyone that the photographic portrait is intended to be a representation of the person within it, so the ultimate choice should be a place the subject identifies with personally. I took Mori’s portrait on the steps leading up to his house as he wanted to be pictured with his garden. After each portrait, we recorded short monologues from each shield bearer describing their work and understanding of the kuman design.

A typical scene in the lead up to election day, Okuk Highway, Kudjip, Jiwaka Province, Papua New Guinea, 2017; photo: Eric Bridgeman, courtesy the artist.

Halfway through our photographic expedition, the town and neighbouring villages were swept up by election mania as nominations for Governor and federal parliamentarians were now open. A cavalcade of trucks, cars and PMVs, overloaded with political supporters chanting candidates’ names, advanced upon the region—giant loudspeakers fixed to the roofs of Land Cruisers circled potential voters for two weeks. Each candidate preached the greatness they would bring to Kudjip and its people while a fusion of gospel, local and doof-doof music filled the small highway town from morning to night.

Early in our group discussions on possible locations for showcasing and photographing the shields we ruled against public interventions taking into consideration the potential for chaos that comes with election time. My own principles for creating work in PNG has always been to keep the process privately contained within the Haus Man until a safe moment arises for its introduction into the community. We were down at the local stream, Wara Kani, shooting the final group of portraits when I had a last gasp of bravery to place the final shield painting among the busy betel nut market. The kuman pictured, belonging to Paul Nulai, was a unique contemporary design resembling an abstract modernist painting, but was locally identified as a cancerous mouth filled with blood red buai (or betel nut). I normally avoid working in the public space—although I’m a regular visitor to the area and known to most residents, I will always be a spectacle. The combination of my local status as ‘white man’, my large camera and tripod, and the dazzling shield designs, make for a high-pressure situation.

The simplicity of the finished portraits does not convey the true challenges we faced while composing the scenes. Papua New Guinea is generally a very difficult place to work, though as a photographer who chooses to operate with film and a medium format camera, my main opposition has been natural terrain and elements, prioritising time, and communicating ideas. My obsessive nature contrasts heavily with the cooler temperaments of the other guys, and towards the end of our expeditions everyone’s energy was running thin. I felt the only thing I could do was relax and, as the saying goes round these parts, ‘Expect the Unexpected’.

Mori Kaupa and Stephen ‘Rambo’ Kaupa with kuman at Bengan Haus Man, Kudjip, Jiwaka Province, Papua New Guinea, 2017; photo: Eric Bridgeman, courtesy the artist.

Notes

Eric Bridgeman wishes to thank Moses Mote, Mote Kirua, Mori Kaupa, All Yuri Alaiku, Enga, Jiwaka Hauslain and Manmeri involved in the kuman workshop 2017; YAKA (Yuri Alaiku Kuikane Association); Joe Kuman; Bomai Witne; Ruark Lewis; Martin Barry (Brisbane Digital Images); Monash Gallery of Art; Stephen Zagala; Ruth McDougall and QAGOMA; Marita Smith; Andrew Baker. Eric Bridgeman’s project received assistance from Commonwealth Government through its arts funding and advisory body, the Australia Council for the Arts, through a Career Development Grant.

About the contributor

Eric Bridgeman is a photographer, painter and installation artist using video and performance in a variety of applications often to do with masculinity, portraiture, culture and politics.