One step after another: a conversation with Lee Kun-Yong

Con Gerakaris

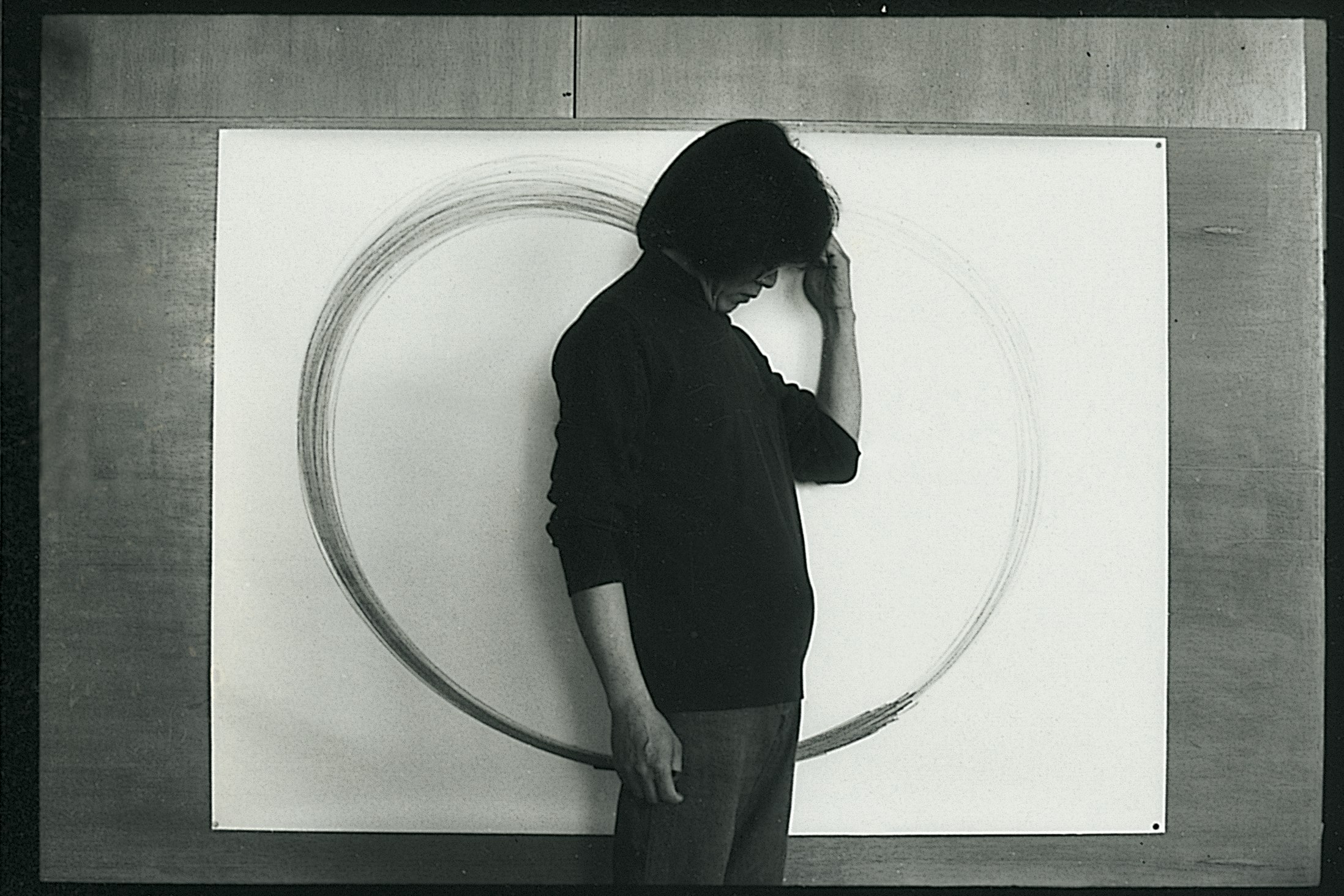

Lee Kun-Yong, Snail’s Gallop (performance view), first performed in 1979, (re-performed in 2018) paper, charcoal, dimensions variable; photo: Document Photography, Equal Area, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, 2018, courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, South Korea.

Performance art is difficult, and difficult to document—photography renders the fluidity of movement static, while video often fails to convincingly capture its atmosphere. It is difficult to discuss, having to justify a transient state of action as a great masterwork of human creativity. It is difficult to exhibit, for obvious reasons.

‘This is very difficult,’ laments Korean performance artist Lee Kun-Yong, as he attempts to eat a biscuit with his right arm strapped to a wooden splint. Eating Biscuit (1975) was the first of four re-performances taking place at the opening event of Lee Kun-Yong: Equal Area at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (4A), an exhibition guided under the principle of collectively rethinking Euramerican narratives of art history and making a just cause for Lee’s ‘undiscovered influence’ (1) within the postmodern performance art canon. Lee, along with Australian artists Emily Parsons-Lord, Huseyin Sami and Daniel von Sturmer, saw that over this past January 4A was reiterated as a place of discourse and collaboration and transformed activities that were framed by its gallery walls into a living document of events, actions and, quite literally, explosions. During this period, I sat down with Mr Lee for a conversation in which we discussed his past and his present, with assistance from an interpreter.

Front: Lee Kun-Yong performing Eating Biscuit (performance view), first performed in 1975, (re-performed in 2018), biscuits, bandages and splints, dimensions variable; commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Art, Sydney. Behind: Lee Kun-Yong, Snail’s Gallop, photographed in 1975 (reprinted in 2017), C-type print; photo: Document Photography, Equal Area, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, 2018, all works courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, South Korea.

In preparation for our conversation I read American art historian Joan Kee’s widely referenced Tate Papers essay Why performance in authoritarian Korea? (2), and an interview between Lee Kun-Yong and Ryu Hanseung, curator at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, published in the Lee Kun-Yong: Event Logical (3) exhibition catalogue. These articles give a fleshed-out depiction of the artist, however I wished to probe deeper into his experiences in 1970s Korea, a time marked by a growth in heavy industry, a rise in consumer confidence and suppression of individual rights. My interest in the Fourth Republic of Korea—demarcated by the monopolisation of power by Park Chung-hee from 1972 to the dissolution of the Yushin Constitution following the 1980 Gwangju Uprising—stems from the conflicting information available. A confluence of martial law and the establishment of international diplomatic relations resulted in a volatile society of experimental art practice, kidnappings, abuse and disco music. Upon meeting Mr Lee in person at 4A, my preconceived idea of him changed: here was an artist who seemed to always live in the moment, uprooting 4A’s installation schedule and exhibition design all the while playfully creating new work on a whim on a discarded piece of cardboard. I decided that any attempt to scrutinise his past as a counter-cultural rebellious artist who dealt with some traumatic experiences was maybe not the best method of conversing with this 76-year old unconventional yet towering figure of Korean contemporary and performance art. So, as with performance art, when the context changes so should the methodology.

Born during Japanese occupied Korea in 1942 in Sariwon, a small city located 65 kilometres south of Pyongyang, Lee Kun-Yong was a seminal player in the determined beginning of Korean contemporary art. Central to the Space and Time and Avant Garde art collectives, Lee and his peers were rebellious university graduates following in the wake of the Informel movement of the late 1950s. Aware of movements and trends in the international art world through imported and translated journals, Lee termed his performances as ‘Events’ to differentiate his practice to that of Euramerican Happenings or Performance Art, a move that stressed that the artist’s actions and the place in which they were enacted were intrinsically linked, becoming gestures of logical meaning. His Events took place in galleries in Korea and abroad, photographed for documentation material to supplement the display of his physical works on canvas and wood resulting from his actions. All of Lee’s major performances were undertaken during the divisive dictatorship of president Park Chung-hee (who was President from 1963 until his assassination in 1979), whose Minju Gonghwadang conservative party prioritised economic prosperity at the expense of civil liberties.

I asked Mr Lee if re-performing Eating Biscuit (1975), Logic of Place (1975), Snail’s Gallop (1979), The Method of Drawing 76-2 (1976), The Method of Drawing 76-3 (1976), The Method of Drawing 76-4 (1976) and Terrorism is an Enemy of Humankind (2012) evoked any particular feelings or memories. His response was unexpected, explaining that the reaction of his audience at 4A reminded him of the reactions generated from his Events in the 1970s, and performed his works with a desire to move on from traumatic social conditions the works were conceived under. My own reading of the emergence of Lee’s performances is that they are inherently political, championing the individual both in philosophy and action during the rigid society of post-war Korea. Through his rejection of traditional modes of painting—achieved simply by either turning his back to the canvas, or rejecting it entirely—Lee Kun-Yong’s conceptual foundation straddles the line between Western modernist thought and the ideologies of his Korean painting peers in the Dansaekhwa movement: Western logic and defiance of established systems and authority and the Korean concepts of the physical limitations of material and their inability to interact with their audience.

I decided that any attempt to scrutinise his past as a counter-cultural rebellious artist who dealt with some traumatic experiences was maybe not the best method of conversing with this 76-year old unconventional yet towering figure of Korean contemporary and performance art. So, as with performance art, when the context changes so should the methodology.

Lee Kun-Yong, The Method of Drawing 76-3, photographed in 1975 (reprinted in 2017), C-type print; courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, South Korea.

‘There were times when I thought that an artist is not someone who makes something, but who involves in something to reveal the world through relationships’ (4). A mission statement of sorts, Lee Kun-Yong’s bodily interventions stem from the relationship between the corporeal body and structural frameworks, both mental and physical, that seek to contain, constrain or otherwise counteract it. The artist was quite talkative during the opening of Equal Area at 4A, something that garnered a mixed response from the audience. I asked Mr Lee, who addressed the audience numerous times during his performances, if he spoke more than usual when performing in Australia. He explained his father was a church pastor and, having grown up watching and listening to sermons, he became ingrained with a desire to talk and perform in front of a crowd. An admittedly born performer, Lee’s tendency to vocalise during his performances was bolstered after holding an Event at a gallery in Tokyo in the 1980s. A gallery patron commented on his conversational nature, appreciating the effort to actively engage with his audience. Initially only speaking out of necessity during his performances in his homeland—notably the minimal declarations of ‘there,’ ‘here’ and ‘where’ of Logic of Place (1975)—he soon began to explain the concepts explored through his actions. And so, these days Mr Lee relishes the embrace of his eccentricities and has always been sure of the meaning and purpose of his art to use his instructions, actions and gestures as a conduit for an audience to reconsider their physical and theoretical surroundings.

Included in Lee Kun-Yong: Equal Area were prints of Lee Kun-Yong’s debut Events, captured on black-and-white film in the 1970s. In absence of the presence of the artist, these works can only be experienced as static images of flickering moments long passed. In 2018, Lee’s actions were recorded with the inherent immediacy of digital documentation, producing ephemeral images and videos existing intangibly. His performances result in tactile remains that range from an erratically painted canvas to half-eaten crackers strewn amongst wooden splints and bandages. The artist works to a personally defined step-by-step structure, always leaving his mark; a trace of his logical gesture remains, be it definitive brush strokes of paint on canvas or charcoal markings on the floor as he propels his body forward—movement fixed in time. Equal Area gave audiences an opportunity to engage with documentation from his past, to be part of an Event and study the artworks created from his logical actions.

Lee Kun-Yong, Snail’s Gallop (performance view), first performed in 1979, (re-performed in 2018) paper, charcoal, dimensions variable; and Logic of Place (performance view), first performed in 1975, (re-performed in 2018) charcoal, dimensions variable; photo: Document Photography, Equal Area, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, 2018, courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, South Korea.

In the 1970s, Lee Kun-Yong and his peers in Seoul were simultaneously within and outside official culture, showing and performing in galleries and the streets. Tolerated by the government due to their international recognition, the Space and Time and Avant Garde groups were guided by a DIY and counter-cultural ethos, employing the ideas developed during their formal university education in inventive ways to subvert the system. I posed a question to Mr Lee, ‘Did you expect that the works you made in the past would have such longevity and would still be relevant today?’ His response came in the form of an anecdote:

In the early 2000s I went to MoMA in New York and I saw a lot of works by Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns and Jackson Pollock while I was on a group tour with my artist friends. The owner of a gallery was the leader of the tour group, and as everyone was leaving to go to lunch I kept looking around the fourth floor of MoMA. Eventually he approached me and asked me what I was doing. I said I was looking for a wall for my work. Then [the 1970s] and now, I knew I was going to be an influential artist and that my works would be in galleries for others to see after I’m gone (5).

Viewing his work as on par with some of the foremost artists of the twentieth-century, Lee Kun-Yong’s response upon the culture he and his peers created together in post-war South Korea. The Fourth Republic of Korea is a well-documented traumatic time for many in the nation, particularly its creative youth, yet cultivated a hotbed of transformative artistic activity, including the highly collectable Dansaekhwa movement (6) and the recordings of psychedelic rock icon Shin Joong-hyun. Lee’s vigorous practice during an unyielding authoritarian political climate helped establish a platform for the booming, democratic 1980s stage of artists such as Lee Bul, Kimsooja and Ahn Kyuchul, and a society catapulting into international conscious with the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics. I attempted to probe further into Mr Lee’s life and experiences during this time, asking about his relationships with his artist colleagues Kim Ku-lim and Kim Yong-min. He changed the topic and recalled story from his youth:

My father had 10,000 books in his personal library. Whenever my mother felt angry about my father she would throw the books out of the house and say, ‘Because of this book I cannot feed my family.’ I was always surrounded by books, so from a young age I could always read books about human beings and the human mind, so I have always been thinking about psychology since before I was an artist. I continuously studied a lot about the human condition. When I was in middle school and high school I went to the French Cultural Centre and the German Cultural Centre in Seoul and borrowed and read as many of their books as possible. The worst form of art—the one I cannot understand—is Pop Art. At the time I was a teenager, Korea was not that modernised nor industrialised, so I had not experienced the kind of mass production being referenced, so maybe that is why I cannot understand Pop Art.

Mr Lee concluded with a final statement: ‘Art is about doing something useless. We have to push that to the extreme. I made that sentence when I was sixteen years old.’

Lee Kun-Yong, Logic of Place, photographed in 1975 (reprinted in 2017), C-type print; courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, South Korea.

‘Art is about doing something useless. We have to push that to the extreme. I made that sentence when I was sixteen years old.’

I got the sense Mr Lee did not like dwelling on his past—he began rambling off-topic and visually surveyed the room we were in—so I turned the focus of our conversation to the present to re-engage with him. We discussed Emily Parsons-Lord, Huseyin Sami and Daniel von Sturmer and he spoke of them with respect, praising their artistic processes and creative output in his own idiosyncratic manner of speaking. I concluded the interview, the mood relaxed and Mr Lee asked me if I was married, which I was told is a common question in Korean culture. In response, I provided an anecdote of my own about an elderly woman on a farm in regional Buyeo, Korea, who invited me to her house and subsequently showed me photos of her daughter in an attempt at international matchmaking. Mr Lee told me I had ‘missed out’. As we casually chatted into the late afternoon I repeated Mr Lee’s modus operandi in the back of my mind: if art is about doing something useless, maybe performance art isn’t as difficult as I thought.

Lee Kun-Yong: Equal Area was produced and presented by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 20 January – 25 February 2018. Curated by Micheal Do and Mikala Tai, Con Gerakaris acted as Curatorial Assistant for the project.

Notes

(1) Micheal Do and Mikala Tai, Lee Kun-Yong: Equal Area, exhibition room sheet, 20 January – 25 February 2018, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, unpaginated. (PDA to link to PDF)

(2) Joan Kee, ‘Why performance in authoritarian Korea?’, Tate Papers (23:2015). Accessed 10 April 2018.

(3) Ahn So-hyun, Lee Kun-Yong: Event Logical (Seoul: Gallery Hyundai, 2016).

(4) Lee Kun-Yong as quoted in Lee Kun-Yong, Lee Kun-Yong (Seoul: Lee Kun-Yong and aMart Publications Inc., 2012), 26.

(5) The artist in conversation with the author, 23 January 2018, Sydney. All other quotes from the artist taken from the same.

(6) Colin Gleadell, ‘The dansaekhwa bubble? 1970s Korean art phenomenon sees meteoric rise’, The Telegraph, 6 June, 2017.

About the contributor

Con is a curator, arts administrator and writer and currently is the Curatorial Program Manager at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art.