Running round history: Yu Araki’s difference

Micheal Do

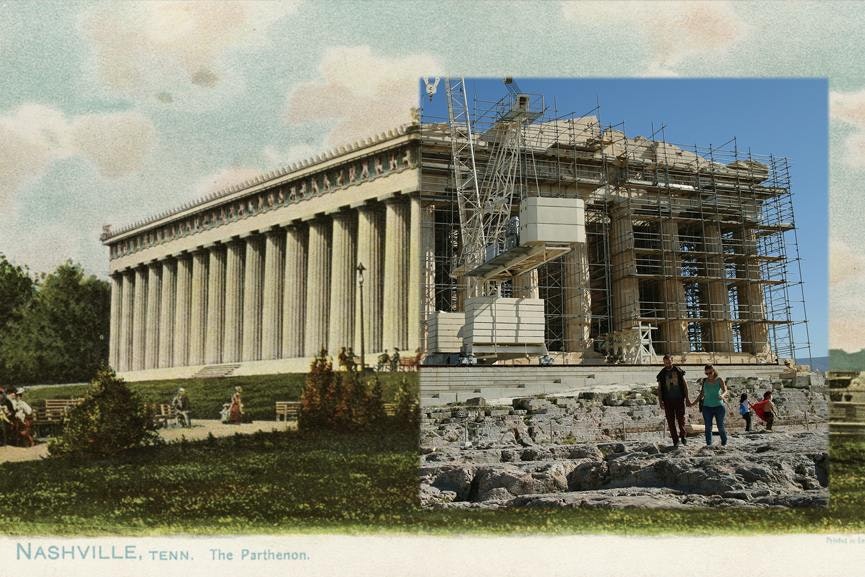

Yu Araki, Sketch for The Temple of The Templet (2015), digital collage. Courtesy the artist.

When discussing Japanese art and culture, it is all too easy to foreground Japanese contemporary cultural production through the gleaming figures of anime film, or the complex narrative tropes of manga. It is no surprise, then, that a number of Japanese artists have drawn from this pop cultural strata to generate and shape their art making (1). Most notably, and arguably Japan’s best known artist, Takashi Murakami developed his landmark Superflat (2001) theory and exhibition marketed as ‘an essential guide to the best of Japanese contemporary art’ along these lines (2). Murakami’s exhibition toured to the US and was followed by his bombastic envisaging of the subcultural ideas of kawaii (cute) and kakkoii (cool) in Little Boy (2005) exhibition of graphic work at the Japan Society of New York. His use of such tropes shaped popular understandings of Japanese art and contemporary culture as transmitted abroad, along with peers Nara Yoshimoto and Mariko Mori, who were part of his cohort of artists born in the late 1950s and 1960s (3).

English sociologist Adrian Favell has observed, many ‘Western curators and art publishers have lined up to produce the selective vision of contemporary art in Japan adopted by him,’ and for many Western audiences Murakami ‘turned the nation into a kind of cartoon’ (4). It is against this cultural context that Japanese artists who studied in the early 2000s were reared—learning, unlearning and blurring Murakami’s version of Japan. This era was marked by an exciting cultural movement where artists, emerging from the austere tech and real estate bust of the late 1990s, could begin to envision a career in contemporary art (5). The conservatism of the Tokyo University of the Arts was changing, an institution that has been slow to accept the new forms of contemporary culture, along with the proliferation of non-commercial art spaces and institutions taking the place of Kashi Garo (rental galleries where artists could pay to show their work), which up until this point dominated the mainstream gallery scene (6).

Tokyo-based artist Yu Araki falls into the category of artists who began practicing during the rise of Superflat and neo-pop artists led by Murakami’s technicolour ideal, instead contributing to a greater nuance of understandings of Japanese art in his moving image practice. It is against this high-octane commercialism and bombastic palette that Araki makes work rooted in local Japanese histories that open up larger conversations about conceptions and paradigms of Japanese identity.

It is against this cultural context that Japanese artists who studied in the early 2000s were reared—learning, unlearning and blurring Murakami’s version of Japan.

Araki’s The Last Ball (2018) refers to a short story written by renowned Japanese author, Ryunosuke Akutagawa, The Ball (1920). Written in response to Pierre Loti’s The Ball in Edo (1889), Akutagawa’s short story reframes Loti’s tale of a ball hosted by the Japanese government for their foreign visitors; the text suggests sarcastically and disparagingly that the Japanese should mimic European sensibilities while noting that the Japanese guests have a ‘strong resemblance to monkeys’ and, ironically, are ‘marvelous imitators’ of European society (7). Akutagawa’s story is told from the perspective of a Japanese woman who reveals her own anti-European sentiment recounting their strangeness. The counter orientalism of the text has since become and influential case study of reclaiming culture. Composed within two large screens, Araki’s The Last Ball is set in a 1883 Rokumeikan building that was once a venue for numerous social and diplomatic events until its demolition in 1941 that typifies the type of setting for Akutagawa’s ball. The two protagonists waltz to Johan Strauss II’s The Blue Danube—an intertextual reference to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey which Araki is particularly fond of—while holding selfie sticks with iPhones that are recording video. This footage, each feeding into one screen, is intermittently overlaid onto other footage shot by a visible film crew in the background which features on the adjacent screen. This technique of a visible double projection or blurring speaks to different modes of seeing and interrogation of the veracity of image-making made famous in the writings of Marshal McLuhan and especially of James J. Gibson’s The Perception of the Visual World that deals with Gestalt psychology and the orientation process. In this way, Araki’s nostalgia for the past is central in his self-reflexive query of Japanese identity and popular representations. He uses this cultural material as inspiration combined with more contemporary film practice to deconstruct, negotiate and alter broader conceptions and understanding of Japan.

However, Araki’s interest in tradition does not extend or typify the familiar—and perhaps often overstated—roots of east Asian beliefs including animism, polytheism, Buddhism or Confucianism. When asked about this, Araki reveals that he was brought up both in America (in Nashville) and Japan. He explains that his bilingual and bi cultural worldview results in a work that exists in an in-between space and the desire to make sense of the world in both contexts simultaneously. He tells me, ‘It’s the tension where they cross over that is interesting to me’ (8). It is against this thinking that Araki describes his art practice as ‘sculpting in time.’ In both sculpture and cinema, the process of casting is foundational to the medium. Recognising the multiplicity of the word in different context, Araki explains, ‘In sculpture, one is making copies. While casting in cinema is making a role of another person. In this way, I’m really interested in the prefix of re.’ Of Latin origin, Re occurred originally as a loan word in Latin, used with the meaning ‘again’ or ‘again and again’ to indicate repetition, or with the meaning ‘back or backward.’ In this way, ‘moving image is all about the re. To revive, to replay, to revisit, to reconnect, to reproduce, to record, to remake, to reinterpret, to remake.’

Yu Arakai, Temple of The Templet (2016), two-channel HD video, silent, loop. Installation view at Yokohama Museum of Art, 26 February 3 April 2016. Photo: Shintaro Yamanaka.

Araki’s interest in re is highlighted in Temple of the Templet (2016) first presented at the Yokohama Museum of Art. The centrepieces of the work are two replicas of the Parthenon, the first located in Nashville, Tennessee, United States of America and the other Edinburgh, Scotland. The viewer first experiences the artist circling the perimeter of the Nashville Parthenon in a red Adidas suit. Historically, Nashville has been colloquially known as the ‘Athens of the South’ because of the city’s focus on education. The Nashville Parthenon was constructed as a temporary structure in 1897 for the Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition to celebrate Tennessee’s one hundred years of statehood. After gaining popularity among tourists and residents, the structure which exists today was rebuilt in 1920. It is the only full-scale replica of the Parthenon in the world and a site well known to Araki during his adolescence and teenage years through school excursions and visits. Projected on the verso of this screen is the National Monument of Scotland, a structure that was modelled after the Parthenon in Athens that was intended to be a memorial for those who died in the Napoleonic War. Construction began in 1826, but due to lack of funds, the structure was never complete and left unfinished in 1829. In Temple of the Templet Araki circles this monument in a blue tracksuit. By using these two replica memorial structures as the symbolic core of his work Araki explores the tensions of national projections of visual, cultural and political history; endlessly running around these structures the artist maps their physical presence, while also attempting to comprehend the cultural and social meaning of each memorial. Through this simple act, Araki engages with the histories of these two distinct geographies to drawing connections to neighbouring societies and revealing that ideals and problems are inherently similar and shared in nature, and in doing so reveals particular modes of knowledge and cultural production that remain trapped in a colonial framework.

This desire to understand the origins of ideas, histories and objects runs as a connecting thread through Araki’s work. The artist tells me that growing up in America his first name, Yu, was naturally understood phonetically as a pronoun. Coupled with the fact Yu is an non-gendered name in Japan, Araki was constantly required to explain himself and his culture to non-Japanese peers. It is this fascination with language and how language can falter and change across different cultures that informs Araki’s modus operandi. ‘It’s a reason why I don’t normally write scripts. I often adapt someone else’s stories. I like to think about different contexts where I can be inserted as a filmmaker and let these places inform my own output.’ In this way, Araki’s work both occupies the space of performance and documentary, two labels which pull and push depending on the individual artwork and more accurately, during different moments within his works. He tells me, ‘There seems to be a lot of conversation about preserving traditional forms, architectures, etc. in Japan. However, tradition cannot survive unless it slowly adapts to the current situation. We can’t just hermetically seal everything. We need to keep making slight changes, and updates to all these traditional forms.’ And in this way, it is not the legacy of Superflat which lives in artists like Araki, who were working within its aftermath, but rather the desire to map the spectrum of a society in order to deal with its complex visual, political and social history.

Notes

Notes

(1) Karen Higa, ‘Some Thoughts on National and Cultural Identity: Art by Contemporary Japanese and Japanese American Artists,’ Art Journal 55:3 (1996): 6–13.

(2) Kristen Sharp, ‘Superflatlands: The Global Cultures of Takashi Murakami and Superflat Art,’ ACCESS: Critical Perspectives on Communication, Cultural & Policy Studies 26:1 (2007) 39–51.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Adrian Favell, ‘Visions of Tokyo in Japanese Contemporary Art,’ Impressions: Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America 35 (2014) 69–83.

(5) Adrian Favell, ‘Resources, Scale, and Recognition in Japanese Contemporary Art: “Tokyo Pop” and the Struggle for a Page in Art History,’ Review of Japanese Culture and Society 26 (December 2014) 135–153.

(6) Ibid.

(7) David Rosenfeld, ‘Counter-Orientalism and Textual Play in Akutagawa’s “The Ball” (‘But l kai’),’ Japan Forum 12:1 (2000) 53–63.

(8) The artist in correspondence with the author, October 2019. All further quotes from the artist from the same source.

About the contributor

Micheal Do is a curator, programmer and writer working across Australia, New Zealand and Asia. His curatorial focus lies in developing thematic and immersive exhibitions that extrapolate research and artistic practices into contemporary contexts.