Cyber ciphers: Pixels, people, participation and politics in the art of Sunwoo Hoon

Soo-Min Shim

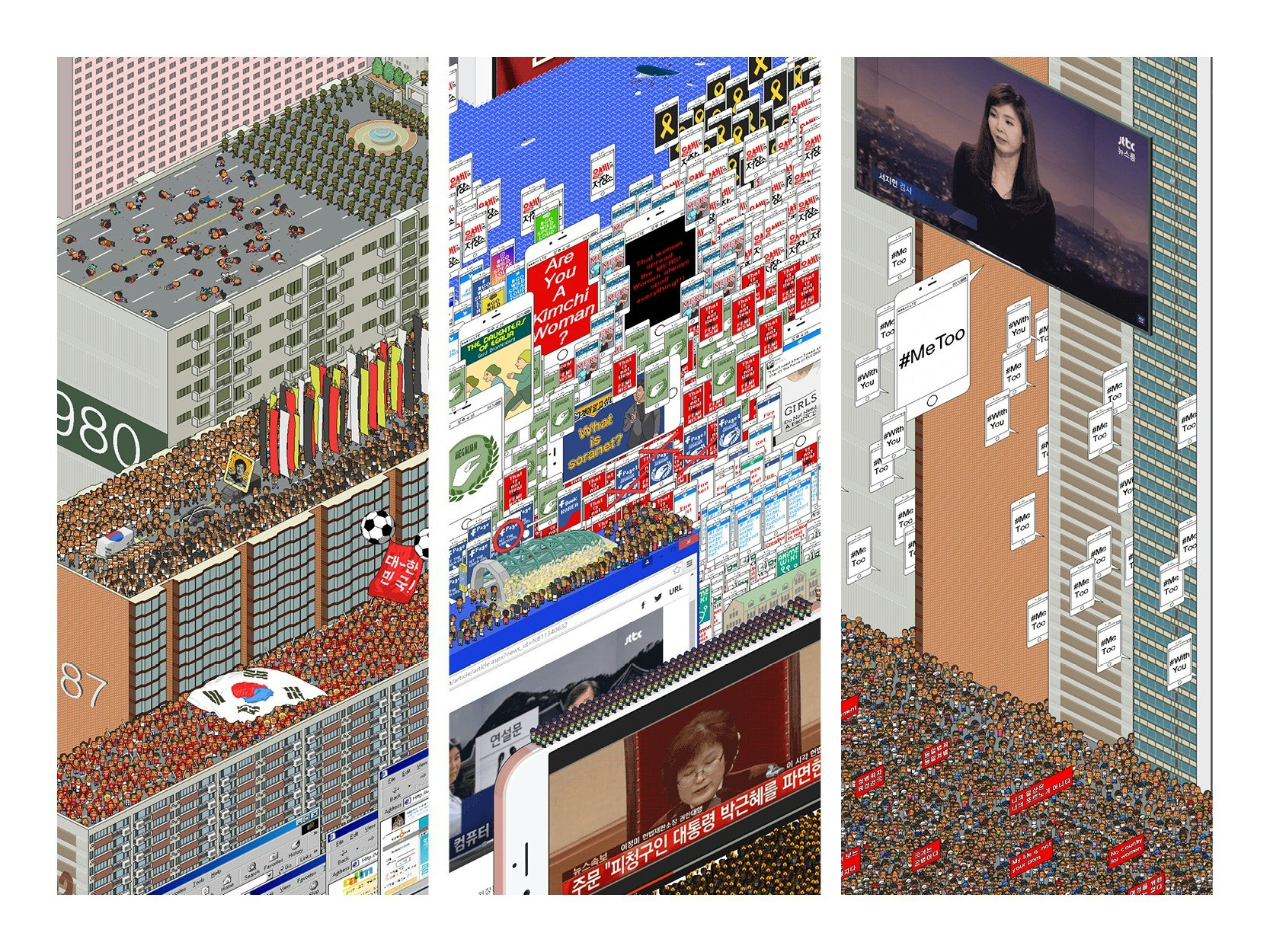

Still images from Sunwoo Hoon, Flat is the New Deep (2017–), digital drawing, commissioned by Gwangju Biennale 2018 with support from Christina H. Kang. Courtesy the artist.

Access the Korean version here.

2002, Seoul

Growing up in Seoul, I regularly frequented the city centre around Gwanghwamun Square. It was often empty of the city’s residents, excluding some tourists taking photographs. However, I recall in 2002 the streets around the Square were filled with hundreds of thousands of people dressed in red, enthusiastic supporters of Korea’s national team’s unexpected success as so-called ‘giant killers’ in the FIFA World Cup co-hosted by South Korea and Japan. As it turns out, South Korean artist Sunwoo Hoon, thirteen-years-old at the time, was one of the celebrators. This site, historically associated with state authority and resistance, had transformed into a place of revelry and festivity. If not at Gwanghwamun, I was relegated to the computer where I read webtoons (웹툰) with my cousins. These long vertical comic strips were published online and read by scrolling downwards. Glued to my monitor, my first online social interactions were with these pixelated people living and existing in detailed cyber landscapes. Here, web and physical sites were conflated.

2017, Seoul

When I returned fifteen years later in winter, Gwanghwamun was pulsating and every street in its vicinity lined with snow and bodies. These people were not dressed in red but instead donned canary yellow ribbons. Each person held a candle in one hand and their phone in the other. Jubilant sports chants were replaced by solemn silence at this candlelight vigil of over 100,000 people, mourning the 2014 Sewol ferry disaster that had three years earlier resulted in the death of 304 people when the passenger ferry capsized off Jindo Island of which more than three quarters were students. Stalls lined Gwanghwamun and at the centre of these stalls was a large papier-mâché effigy of President Park Geun-Hye with a noose around her neck. Signs demanded her resignation and impeachment, after several corruption scandals and her delayed response to the Sewol disaster was taken as evidence of her incompetency as a leader.

Everyone gathered looked towards Gwanghwamun Palace, adjacent to the Square’s northern side, photographing and sending KakaoTalk messages on their phones—connected corporeally and virtually. Again, Sunwoo Hoon was one of the many faces at the Square that night, turned towards the presidential house and the sky in sorrow. People had come together, not in solidarity of nationalistic pride but in grief, remembrance and indignation. Public spaces like Gwanghwamun, stand as a stage for the shared experiences of the nation, broadcasting narratives of national aspirations and grievances that are collated into the collective meta-narrative of the nation. These mass gatherings are national spectacle and makes visible the body of the nation. Standing in these crowds, there was a profound sense of history-making.

2019, Sydney

Two years later, back in Sydney, I re-encounter Sunwoon Hoon’s installation Flat is the New Deep (2017–) at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art as part of the exhibition The Invisible Hand. Created in the webtoon form and installed on a long vertical monitor, I began to scroll downwards. The work begins with a single pixel that multiplies and proliferates into representations of key events of South Korea’s political history. Instantly, I recognised that my lived experiences have been translated into these isometric structures and individual pixels: I saw the 2002 World Cup celebrations, the Sewol ferry tragedy protestors, and the hordes of anti-Park Geun-Hye demonstrators. Viewing the collation of my subjective memories in these familiar streets, I recognised the importance of place in harbouring and holding the echoes of my remembrances. French historian Pierre Nora has stated that ‘memory fastens upon sites, whereas history fastens upon events’ (1).

Following their attendance at 4A’s exhibition opening, I sat down to talk with Hoon and his sometimes collaborator Mijoon Pak. Through these discussions I come to see Hoon’s work is an archive of memory and history, imbricating sites and events, by conflating the physical and the virtual. In his renderings of architectural space, physical buildings (such as apartments and office buildings) are separated by magnified webpages from Naver and Yahoo! Korea, merging the offline and the online. Likewise, while in Seoul I am aware that the city is an assemblage. Every suburb has visible marks of different histories, characters and pathologies—a palimpsest of gentrification, war and industrialisation. Space itself is constructed as polyphonic, a layered cacophony. In cyberspace, it is the same. These contested layers and juxtapositions of images are compressed into a single strip, presenting Korea as simulacra.

Instantly, I recognised that my lived experiences have been translated into these isometric structures and individual pixels.

21C, Korea

It seems apt, then, that Hoon presents Korean history through the localised webtoon form. The term webtoon itself is a combination of web and cartoon, a hybrid word coined in the early 2000s in Korea. Valued at KRW 724 billion Won (around AUD 899 million) in 2017 (2), the webtoon industry continues to be significant in Korea. It can be argued that the webtoon is an inherently democratic form; when it was introduced as a new form of digital content it bypassed a number of distribution channels and the internet became a place for artistic freedom. Seeing the webtoon as a powerful visual language tool, it also acts as a kind of sociological imagination device that allows readers to share and comment. In this sense, the webtoon is the vehicle for Hoon’s discursive dive into sociological behaviours and public space. Hoon recognises the locality of the medium: ‘The genre of Korean webtoon is thought to be unique. I draw webtoons with big monitors in mind, but people look at them with their mobile phones. Webtoons are to be enjoyed anywhere anytime in the mobile environment’ (3).

The claim is constantly made that South Korea is the most wired nation in the world, the most wireless and, since at least 2017, enjoys the fastest average internet connection (4). Studies into webtoon digital cultures have revealed that Korea’s rapid growth rate in the online cartoon market may be attributed to the higher penetration rate of mobile devices (5). With the widespread adoption of smartphones by 2009, and the popularisation of the iPhone soon after, Hoon immediately started investigating the smartphone as an art form but also the myriad ways that technologies alter epistemologies and ontologies. Hoon began creating webtoons in 2014 with his webtoon Damage Over Time published on Daum. His time during military service would further catalyse his interest in democracy, politics and social justice. As Hoon explains, he began experimenting with the form earlier in 2009–2011:

My work began during my time in compulsory military service, where I had lots of free time and an old computer and drew pictures on Microsoft Paint one after another. In the military camps, no soldier is allowed to use USBs or the internet. I started drawing in February 2011 when I became a driver for the Colonel. My primary duty was to serve teas for visitors to him and the office I was in had an old computer without connectivity. I doodled around with the Microsoft Paint tool, sketching the vehicles that I drove or the soldiers in their uniforms.

Considering Seoul’s status as a leading digital city, understanding and comprehending the ways that technology filters our world and our perspectives is important to interrogate and, as Hoon tells me in conversation, he ‘spots changes in images shown in media’. In Flat is the New Deep cyberspace eventually overtakes physical space as a giant iPhone with a campaign poster picture of President Park Geun-Hye looms large. In Hoon’s webtoon strip, protestors had been standing on the rooftops of generic high-rise apartment buildings found around Seoul, until they become overshadowed by the iPhone. Hoon seems to speculate that with the rise of phenomena like nomophobia—an irrational fear of being without one’s mobile phone—we will spend more time digitally than in physical proximity with one another. Just as physical architecture controls our movements, online spaces controls our virtual movements and behaviours and actively shapes public perception. Indeed, the figure of Park Geun-Hye herself is never rendered in the work but, rather, Hoon is concerned with the ways representations of her have been re-presented, depicting her only via television appearances, news headlines or campaign photographs.

Sunwoon Hoon, The Flat is Political (installation view), 2017, Asia Culture Center, 12th Gwangju Biennale: Imagined Borders, 7 September – 11 November 2018. Photo courtesy the artist.

2018, Gwangju

Following Seoul, I visit Gwangju, a city most famous for the 1980 massacre that occurred there under the Chun Doo-Hwan dictatorship (1979–1988). My parents often speak of 1980, recalling the closure of their university campuses, tear-gas flooding classrooms as police barged in, arresting and beating students and demonstrators. The Gwangju uprising was seen as part of the minjung (민중) movement, a word translated to ‘the masses’ or ‘the people’ that is oft considered the beginning of Korean democracy. Flat is the New Deep chooses this moment to begin as Hoon ‘wanted to show how the public square has changed in Korea to be a safe, joyful place after 1987’. Here, a year prior to encountering the work at 4A in Sydney, I experience it for the first time while on display at the Gwangju Biennale. Themed Imagined Borders, the 2018 iteration of the Biennale was focused on site-specificity, looking to Korean local history and the collective memory of the democratic movement in Gwangju, with one entire section titled The Art of Survival dedicated to Gwangju’s political violence. The Biennale itself was founded in 1995 in memory of the minjung movement and the massacre and in this context Hoon’s work is connected to minjung. While Hoon’s polyphonic colours and webtoon aesthetic may superficially at least seem contradictory to the common optics of a violent struggle for freedom, presented in Gwangju the work is imbued with the exigency of and agitation for political reform. For Hoon, the pixel is an analogy for democracy, symbolising the individual in the collective. This is mimetic of the idealism captured by minjung that prioritised the power of individual citizens to gather into a political force.

Thirty-nine years since the Gwangju Massacre, what place does minjung have in such a technologically-focused society? In the most straight-forward sense, technology has been harnessed to benefit democratic struggle. During the early 2000s in South Korea, increasing collusion between political parties and established news media companies engendered the rise of internet-based web journals, such as the Korean OhmyNews (오마이뉴스) founded in February 2000. On these platforms everyday citizens were free to publish and voice their opinions, a luxury denied to my parents—the ways in which my parents mobilised politically in 1980 and the ways that I do in 2019 are vastly different. With Korean news media largely curtailed by martial law and with access to local news sources only, news of the Gwangju massacre trickled to my parents slowly or via word of mouth; my contemporary reality, which is taken for granted, is that news is instantaneous and transnational.

In conversation with me, Hoon points specifically to labour union leader Kim Jin-suk and her use of Twitter during her 2011 demonstration in Busan. Kim lived on top of a 35 metre high crane in a shipyard in the city’s port for about a year in protest against Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction Co., a multinational shipbuilding company founded in Korea in 1937, who faced strike action by hundreds of its workers in Korea and the Philippines following a mass lay-off. She used Twitter to send messages about her protest by posting about her everyday life in the crane cab to the public. People responded to her by coming to her site on a bus called The Hope Bus and, in 2014 and 2015, Sunwoo Hoon’s peers and colleagues arranged festivals in support of Kim. To signal further support of Kim, Hoon rendered a digital image of Kim and her crane which he then hung on over the façade of a building on his university campus. Hoon had first met Kim during his studies at university: ‘After I was discharged from compulsory military service I joined the university newspaper as a cartoonist. When I attended a talk by Kim Jin-Suk, a labour activist, during college, I started expressing my interest in social issues into my artwork.’

Before this moment, however, Hoon had always been politically aware if not as active. Born in Seoul in 1989, Hoon’s father passed away when he was ten and he then moved to the South Korean city of Jeongeup with a population of 100,000 where his mother was born and raised. There he lived with a new family of his mother, stepfather, grandmother, brothers and sister. He elaborates:

My [step]father drove a bus and mum worked at a local factory. This background, from a remarried family of working-class origin in a provincial area gave me an awareness of being socially marginalised, especially after I went to art school where the majority of my classmates were from prestigious art high schools and well-off families. I started getting interested in social issues.

Sunwoo Hoon public intervention, 2018. Photo courtesy the artist.

2018, Gwanghwamun

Staying with my grandmother in Seoul, she constantly reminded me to avoid public toilets in Seoul. Blaming her concerns on conservatism, I did not heed her warning and entered the women’s toilets at Gwanghwamun station. On nearly every surface of the doors, walls, nooks and crannies were stickers calling for the ban of the mollacam, shortened to molka, and otherwise known as the SpyCam. These 1mm-wide-lens cameras have been found hidden in public spaces, such as toilets, dressing rooms and motels, filming women and then distributed and live-streamed online. Nearly 6,500 SpyCam crimes were reported to the police in in South Korea in 2017 (6).

Gwanghwamun was completely occupied once again, yet this time I noticed that most of the demonstrators were women, here to demonstrate against the molka. Again, they shared news of the protests through their phones, the sounds of camera shutter noises resounding through the square. I later discovered that all smartphones sold in South Korea are required to make this loud shutter noise when taking photographs as a measure to combat SpyCam crimes and so-called ‘upskirt’ camera shots. The protestors held signs reading ‘My life is not your porn’ and ‘No country for women.’

These signs have been replicated in Flat is the New Deep as Hoon has depicted this ongoing struggle for women in Korea, from the #MeToo movement to the genesis of the feminist internet group Megalia in late 2015. Megalia is a controversial feminist online forum which allows users to anonymously share extremist feminist ideas. Hoon offers:

Life in the military was painful and it came to be a motif in my webtoon series. My hatred of this hyper-masculine culture was the impetus for the creation of my artwork, and the feminism course that I took at university was an important influence on me. I always saw myself as underprivileged and it was eye-opening to learn how my gender can be a privilege.

Hoon further explains that in the webtoon world, webtoon artists created t-shirts with Megalia’s symbol to support feminists:

Megalia relied on crowd-funding to operate and one of the women who donated to the group posted her support online which led to her sacking by her employer Nexon, a video game publisher due to strong protests from male gamers. This triggered serious battles between men and women in the game industry which is mainly male-dominated. People protested in front of the Nexon building and they wore t-shirts with a sign ‘Girls Do Not Need a Prince’. There are many women webtoon artists.

Indeed, this backlash represents the extent to which Korea is now enmeshed in the vanguard of new cyberpolitics. As much as web spaces have been used to proliferate awareness and share knowledge, they are also spaces on congregation for bullying and denigration. Halfway down Hoon’s webtoon strip, a horde of iPhones overlap, multiply, and metastasise into an overwhelming mass of conflicting opinions on feminism in Korea. On one of the larger screens appears the striking question, ‘Are you a Kimchi woman?’, alongside smaller screens with the Megalia logo, referencing the propagation of discriminatory sentiment and rhetoric online. In 2015, the internet forum DC Inside started MERS Gallery as a forum to share information on the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak across South Korea. There, a false rumour appeared that two Korean women contracted the MERS disease when they refused quarantine to go on a shopping trip to Hong Kong. From there, the word kimchi-nyeo or ‘Kimchi woman’ was used to vilify women by perpetuating the stereotype of superficial women. Hoon’s work provides the caveat of an unbridled reliance on the internet for accurate information, providing a more multi-faceted commentary on Korea’s technological embrace.

The Invisible Hand (installation view), 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, July 2019. Left: Sunwoo Hoon, Flat is the new deep, 2018, digital drawing, dimensions variable. Commissioned by the Gwangju Biennale, 2018 with support from Christina H. Kang. Courtesy the artist. Right: Sunwoo Hoon and Mijoon Pak, Flat Earth, 2019, digital drawing, dimensions variable. Commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, Australia. Courtesy the artists. Image: Kai Wasikowski

Another such event that Hoon incorporates within Flat is the New Deep, is the US Beef Protests in 2008. Up to one million South Koreans protested their government’s reversal on banning US beef imports which had been in place since 2003 when mad cow disease was detected in US beef cattle. These protests were known for being led by South Korean teenagers mostly via social media, an affirmation of online platforms as vehicles through which to enact democratic change. However, the use of social media was criticised by government authorities and media critics as comments made by protestors had little basis in science and rumours had taken root quickly before the government or mainstream media could verify. Eventually Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation televised a program on 27 April 2009 titled ‘Is American Beef Really Safe from Mad Cow Disease?’, which precipitated mass demonstrations. With complaints from the South Korean Agriculture Ministry, the central prosecutor’s office formed a team to investigate the claims made by the media program that downer cattle were suffering from BSE, which turned out to be scientifically untrue. By referencing this event, Hoon signals the contemporary post-truth paradigm in which technology circulates and propagates false information, leading to the destabilisation of an informed public, a necessary condition for a successful democracy.

In the complex triumvirate of people, participation and politics, the individual in Hoon’s webtoon is anonymous, subsumed entirely by the crowd and the collective. Paradoxically, while the internet may atomise individuals physically it also homogenises mentalities. Hoon’s ‘flattening’ symbolises the proliferation of fake news and groupthink as the individual and the collective collude and collide. As his webtoon progresses downwards, getting closer to our contemporary moment, the spaces between the buildings are compressed. This is a literal and metaphoric evocation of the idea that there is less room for political discourse and only more room for myopia. Patterns of socialisation are replicated in these alternate worlds, if not amplified. In Hoon’s words, ‘The history of the internet is similar to the history of the world. People’s behaviour there reflects reality in that people are in conflict, engaging in battles there and if the scale gets bigger into the national scale eventually, people can be organised to act in a certain way.’

Just as Gwanghwamun is a space with imagined and material boundaries, used to embody and stage various ideologies, so too is malleable cyberspace a morass of opposing viewpoints, conflicts and discord. In the limitlessness of these spheres, we erect and construct new communities, barriers and boundaries. How do we regulate something so unquantifiable and porous? The public’s memories are shaped by ceremonies, museums, statues, monuments and national holidays that in turn construct the delineations and identities of specific groups. Today, these groups exist online. This shift has led to the democratisation of histories, allowing anyone to record and access while privileging individual, personal, autobiographic memories. Our tweets, texts and Facebook messages are logged and archived on servers, our digital footprints monetised. The technological advancements of every era and epoch inevitably transform history and memory. However, like any historical artefacts, our digital interactions are susceptible to semiotic readings. They wait for artists and historians like Hoon to decode, deconstruct and unravel, the complex, plastic messages within them.

Sunwoo Hoon’s Flat is the New Deep (2017–) was presented in The Invisible Hand, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 28 June – 4 August 2019.

Notes

(1) Pierre Nora, ‘General Introduction: Between Memory and History,’ in Realms of Memory, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 18.

(2) ‘Webtoon makers leaving Korea for US, Japan,’ The Korea Times, 1 August 2018.

(3) Sunwoo Hoon in conversation with the author, Sydney, July 2019. All other quotes from Hoon from this source.

(4) Akamai’s [State of the Internet] Q1 2017 Report.

(5) Jennifer M. Kang, ‘Just another platform for television? The emerging web dramas as digital culture in Korea,’ Media, Culture and Society 39:5 (2017) 762–772.

(6) ‘South Korean women turn out in their thousands to protest against widespread spycam porn crimes,’ The Telegraph, 7 July 2018.

About the contributor

Soo-Min Shim is an arts writer living and working on stolen Ngunnawal and Ngambri land.