The foundling and the fire: improvised life between cultures

Helen Grace

Akiko Fujita 藤田昭, Flame Tree, 1990, Kingswood; photo: Noelene Lucas.

In the fields with which we are concerned, knowledge comes only flashlike [blitzhaft]. The text is the long roll of thunder that follows. (1)

Initially quarantined outside rather than inside universities, art schools have become precarious in Australia today, as universities themselves have taken up the idea—rather than the practice—of creativity as a management mantra. How do we go about ‘creating the conditions for energy to be produced rather than depleted by academic life on an everyday basis’? (2)

Akiko Fujita 藤田昭, Flame Tree, 1990, Kingswood; photo: Noelene Lucas.

1990

August, the crisp air of late winter, the beginning of a new semester in a very young university, barely a year old. On the grass in front of the VAPA (3) Dean’s Unit, a large-scale ceramic sculpture is emerging from the pyre of an open-air kiln, fired by piles of red gum, gathered and brought to the campus by the Army, commandeered by an enterprising and imaginative lecturer for this civilian aesthetic purpose. Akiko Fujita 藤田昭 is Artist in Residence and her fiery creation, Flame Tree, and residency, alongside others on the Kingswood campus of this period, is the rhizomatic result of earlier grass-roots artistic engagements with Asian art—in this particular case, from Japan (4)—that had developed in the 1980s (5), the precursors of what became Asialink’s residency program. The University of Western Sydney (UWS) becomes a new locus of this activity around 1987, when Australian sculptor Noelene Lucas takes up a position there with a growing expertise in this history, following an artist’s residency in Japan. The fire sculpture by Fujita is part of a long practice by the artist that involves such earth works, literally made from the soil of the location (6). The work resonates here, on the edge of metropolitan Sydney as it bleeds into the base of the Blue Mountains, because of the memory of earlier fire sculptures by Joan Grounds, another UWS lecturer from 1992 (7). Lucas and Grounds are key figures in a movement based at UWS to engage with regional art and are instrumental in the expansion of residencies and exchanges in this period (8). Both artists participated in early exhibitions in Thailand (9), in addition to residencies and exchanges that followed there as well as in Vietnam (10), and their network remains active today.

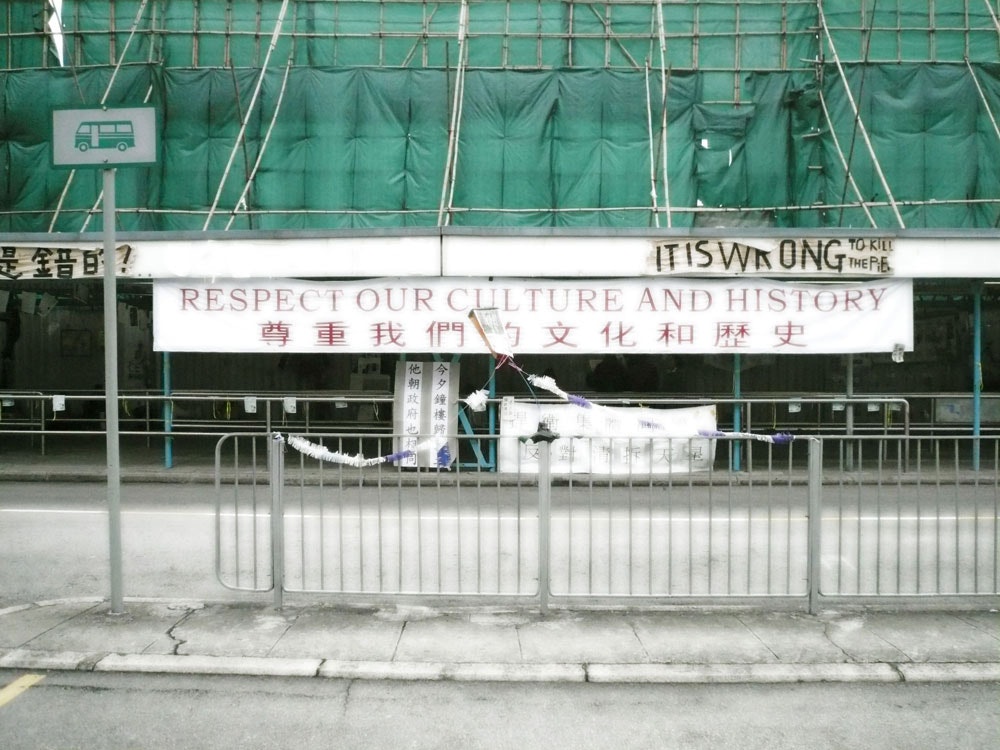

Queen’s Pier demonstration, Hong Kong, 21 January 2007; photo: Helen Grace.

1993

I am on my first study leave in my first full-time academic job, after years of precarious teaching, and I return to Australia to find that I’ve been assigned classes in ‘non-Western art’ and ‘postcolonialism’—not my fields, but I accept the invitation to take the path less traveled in these parts. It is a decade or two since this ‘foundling’, now passed to me, had been left at the doorstep of the academy in Australia; we in art history and theory are slower to respond to the changing world than the studio artists seem to be (11), and we think we need to do more research before we can venture in (12).

1972

In the middle of heated debate about the teaching and collection priorities of the then newly-established Power Institute at the University of Sydney, Patrick McCaughey (13) encapsulates the state of play, in a defense of the (Euro-American) status quo:

The question of teaching Asian art is certainly a vexatious one. Nobody is doing it and it clearly must be done. From the outset the Power Institute has wanted to include Asian art in its curriculum and collection. Finding scholars to come and teach it is one major problem, and the dearth of collections, except in Melbourne, is another. No doubt the new Power Foundation will make Asian art one of its babies. It is certainly a foundling at present. (14)

Here and now

Whether this foundling infant, placed in 1972 in the ‘too-hard basket’, has yet found a home in the Australian academy is still up for debate. Certainly, the recent announcement that Judith Neilson has donated AU $6M to establish a new chair in Contemporary Chinese Art at the University of New South Wales (15) is a significant development, reminiscent of the earlier establishment of the University of Sydney’s Power Institute under John Wardell Power’s bequest (16). In both cases, a strong personal interest motivates the initiative and it will be some time before we can compare the outcomes. But there is no doubt that the ground has shifted dramatically in the 45 years since Donald Brook dared to suggest that western art was merely ‘one rather inaccessible regional manifestation of art’, and that ‘if the art of the region were taken as the prime study, the Power Institute could be internationally tops’ in a decade or two’ (17).

Asian art historians Olivier Krischer and Stephen H. Whiteman note that Antipodean interest in Asia has a cyclical quality, appearing every five to ten years (18). And yet, this quality applies to all cultural endeavours in Australia with nothing ever seeming secure. Processes of circularity and repetition mark this insecurity and the improvised ways in which the intellectual’s work is undertaken, with its tentative steps and its disruptions. If colonial experience and history constitute Antipodeans as peripheral, obliging us to set off in search of the centre, always thought to be elsewhere, along this journey we find that the centre never holds and we are permanently off-centre, sometimes in the middle of nowhere, sometimes, by accident, in the place where everything is happening. This oscillation also informs the memory of events, so that the actual continuities of ongoing cultural exchange are variously hidden and uncovered, forgotten and remembered, as time passes. From time to time, public policy shifts might suggest that a ‘new’ discovery of Asia has occurred, because a change of government or bureaucratic restructure needs to mark its presence, but these seasonal adjustments overlook the persistence of enduring personal networks, maintaining relations beyond the official sphere of foreign affairs. The constant restructure of institutions in the permanent revolution of everyday life that has now become such a part of our cultural landscape is a bit like the reformatting of hard drives—erasing the memory of what was there as everyone starts afresh—and it is this process that seems to provide the only continuity: cultural amnesia in perpetuity. Actually, memory itself requires forgetting—yet flashbacks recur…

MTR, Hong Kong, 2007; photo: Helen Grace.

1993

The team effort at UWS required to teach the ‘Combined Studies’ program for art, design, theatre and dance students is necessarily performative; we have a diverse student body, and we can’t rely solely on the force of Western theory and its categories to explain the world. How to open thought to what does not lie within the conceptual confines of its location? How to unsettle thinking for students and teachers alike, whose markers of what counts are predominantly European and North American, without rejecting the force of knowledge from these places? What, exactly, is Australian culture? How does multiculturalism work, or how does it not? In a polemic that applies more widely in this vein, the Cuban critic Roberto Fernández Retamar responds to the question, ‘Does Latin American culture exist?’ by rewording it to reveal its meaning for the Latin American to whom it is posed: ‘Do you exist?’ He appropriates Shakespeare’s Caliban as a symbol of the mestizo experience of colonised peoples. He is aware of the ambivalences of appropriating a symbol ‘that is not entirely ours, that … is also an alien elaboration’ (19) and yet the use of this ‘alien elaboration’ to describe the devalued local is, he acknowledges, ‘based on our concrete realities’. Staying, ironically, with the Bard for a moment, in a lecture on postcolonialism I invite two young theatre students to perform a short passage from The Tempest, in which the imprisoned Caliban, filled with rage and contempt, spits out the truth and ambivalence of language and colonisation:

You taught me language, and my profit on’t

Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you

For learning me your language! (20)

1992

An exhibition at Space YZ, a transitional space between two buildings on the UWS campus, is one of the first in the country to feature Australian-based Chinese artists, who have settled here in the aftermath of Tiananmen (21). Space YZ is in its first year of existence, generated by the artistic possibilities of using an otherwise unusable broad corridor. The gallery links Z Building, the new Visual Arts Studio complex, with the rest of the campus, replacing the very improvised off-campus factory building in Peachtree Drive, Penrith, where for several years the studios were located. The artists, too, are transitioning between formal training in China and the informal and precarious economies of recent immigrants to Australia. The leader’s emotion, in the 1989 Tiananmen tears of Prime Minister Bob Hawke, has granted asylum to 16,500 Chinese students and others, including some of these artists. Several of the artists will become globally prominent, but right now, in 1992, there are few other Sydney galleries where their work is seen. They are survivors of a generation of unprecedented change in China.

Chess match underway during Queen’s Pier demonstration, Hong Kong, January 2007; photo: Helen Grace.

1993

Early June. An epic film might convey the sweep of history that one lecture would be hard-pressed to match. In the middle of a screening of Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor (1987), just as the Cultural Revolution is breaking out, a group of students burst into the lecture theatre, wearing Red Guard costumes (22) and brandishing Little Red Books (23), denouncing everyone as ‘capitalist roaders’ and ‘revisionists’. Mao had, after all, told us ‘the revolution was not a dinner party, nor an essay, nor a painting, nor a piece of embroidery’. A long way from the Cultural Revolution, now returned to us as a form of participatory theatre, we are figuring out how to convey the force of history to a group of students, many of whom have already experienced it in their own immigrant/indigenous stories, while we, their teachers, are merely armed with our sophisticated histories of art and theories of the image.

If we are lucky the students will work it out for themselves, encountering the flashlike [blitzhaft] quality of knowledge, as Walter Benjamin put. We improvise from within our lack of resources, and our key performance indicators are whether or not students are engaged; within five years some of them will be among the leading artists, scholars and curators in the world. Meanwhile, a new exhibition has just opened at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (24), signaling the rising dominance of contemporary Chinese art in the global art world. In September, the first Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art is held in Brisbane and the ‘foundling’ is beginning to make itself very much at home (25). Within fifteen years, in the impermanence of things, the Art School of these flashbacks is gone, Visual Art becomes Visual Communication, and the passage of a few persons through a rather brief period of time is complete. The energy that burst forth in that curtailed time of rapid institution building finds other places to flourish.

West Kowloon under construction, Hong Kong, 2007; photo: Helen Grace.

2006

November. The Asian Cultural Co-operation Forum (26) has taken over the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts and, subsequently, a cultural blitzkrieg is under way. This development brings together delegations of cultural ministers and officials from eight Asian countries (27), as well as senior officials (directors, deputy directors, senior curators, et al) from some of the world’s leading museums (Tate, Guggenheim, MoMA, Serpentine, NGA). The ministerial meetings are closed but there is a large ‘Open Forum’ and my teaching department has joined forces with Asia Art Archive to present a conference on ‘Cultural Ecologies: Communicating Contemporary Art in the 21st Century’ (28). Leading scholars and practitioners from all over the world are attending. Simultaneous translation covers the linguistic diversity of these meetings—linguistic politics plays out in the predominance of Putonghua in some sessions, Cantonese in others, English as the go-between for South Korea, Japan and South-East Asia.

This is an intense moment in the attention given to culture in Hong Kong (29), a juncture of pure potentiality when the naming of a concept creates a virtual reality that just might turn real, a field of energies opened for development. It is a time when the ‘soft power’ of culture is adopted in East Asia as a sign of cultural optimism and confidence, diminished somewhat in the West since the end of the Cold War. The West Kowloon Cultural District is forming as a concept and the initial design competition is won by Foster and Partners. The project is conceived as some kind of utopia by the predominantly Western architectural firms bidding for it:

Hong Kong knows how to build dreams, and now this ethereal dream—fabled Xanadu itself—will rise in the golden sunshine of the South China Sea. (30)

In a move that is equally far-sighted, the Museums Advisory Committee subsequently rejects the ‘property development’ model of the general project and argues that a new kind of museum is required (‘M+’), one that could incorporate not only traditional forms of art but also popular cultural forms (music, comics, games, design and all the rest)—’visual culture’ in general (31). This is the context in which I arrive in Hong Kong to set up a program in visual culture studies. Because there had been relatively little art education here (32)—Hong Kong parents, in any case, preferred their children to study more pragmatic and useful things—secondary school policy developments begin to focus on the value of visual culture, and as the art market develops the possibility of legitimate careers in the arts (and especially in arts management) emerge.

Shenzhen, May 2007; photo: Helen Grace.

On the mainland, cultural and creative industries are burgeoning as cities rapidly develop and hundreds of museums are planned, requiring more curators and managers than exist in the entire world. It is a dream landscape, restricted only by the thoroughly political administrative logic of a culture that has invented bureaucracy and meanwhile relies on guanxi關係 /关系 (connections) to get things done.

Settling in Hong Kong, I encounter the ‘reverse shot’ of all those forages into Asia in the 1990s by teams of Australian academics in search of research partnerships, academic exchange and students for Australian universities. And, of course, in Hong Kong the phenomenon is up-scaled as teams from all over the world are attracted to the city principally because English is spoken here and so it is the most convenient gateway to the mainland, the real target of these forays. China is seen as a vast untapped resource, where the establishment of offshore programs by top Western universities would, it is hoped, bring great glory and financial reward to the home campuses (33). Usually the teams know little of the history, politics, culture and languages of the places they move through, as this would require a higher degree of circumspection on their part, and so instead they storm in with assumptions of the universal value of Western concepts and knowledge systems, while paying lip service to ‘Asian values’, confident that the places they are going to will welcome what they have to offer and be grateful for it. For different reasons, these forays may indeed be welcomed by the hosts, as part of a bigger picture of administrative rationality, development and civilisational status enhancement (34).

How to teach ‘visual culture’ in Hong Kong and how to identify the significance of its emergence? I’m guided by a specific critical approach, well-articulated by Susan Buck-Morss:

Thinking globally, but from the particular, ‘local’ position of the History of Art and through the medium of the visual image, a distinct aesthetics emerges, a science of the sensible that in our time accepts the thin membrane of images as the way globalisation is unavoidably perceived. (35)

And there is a challenge to the ways of knowing that underpins the located knowledge, informing my thought until this new location brings a ‘shock to thought’:

How can theory learn from contemporary art practices engaged in stretching that membrane, providing depth of field, slowing the tempo of perception, and allowing images to expose a space of common political action? (36)

The aim is to ‘enter a field of negotiation for the move away from European hegemony toward the construction of a globally democratic, public sphere’ (37). This has precise local relevance in Hong Kong as young activists are challenging the demolition of everyday practices and habits in the reengineering of space that accompanies development in a global city: the first of these struggles which revolves around the preservation of the Central Star Ferry pier is underway at the time of my arrival. It is the intense focus on image production and social media within this campaign that demands attention in figuring out what visual culture means here (38). The Star Ferry campaign will extend to other activist interventions from this time, including the Queen’s Pier occupation in early 2007, occupations of the Legislative Assembly in the debate on the High Speed Rail link in 2009-10, the national education debate in 2012, and culminating in the Umbrella Movement in 2014.

Queen’s Pier demonstration, Hong Kong, 21 January 2007; photo: Helen Grace.

Teaching students in Hong Kong, it’s necessary to immediately acknowledge that, while English-language instruction is considered a privilege and a pathway to social advancement, English is not the mother tongue. So there is an ambivalence, always, especially in the university where I am teaching; an understandable resistance, most marked since 1997 (39). Chinese University of Hong Kong, where I am teaching, had been established by missionaries and neo-Confucians escaping China after 1949. The school’s principle language of instruction is Cantonese, as opposed to the much more colonial institution, the University of Hong Kong, where English is (ostensibly) the main language of instruction. A flood of mainland students is now entering Hong Kong universities, especially their fee-paying (‘self-financed’) programs. Because they may not understand Cantonese, these students (or ‘clients’ in some quarters) prefer that courses be taught in English, which is why they’ve come to Hong Kong after all, rather than heading for the US or the UK, a more expensive option and one that involves greater cultural shock. My university is also trying to attract more international students, obliging it to increase its offerings of subjects in English, and adapting its complex linguistic politics (40).

In the meantime, the majority of my students are Chinese, and whether they speak Cantonese or Putonghua, it is much harder for them to read texts in English. And it happens that most of what I want them to read exists in Chinese editions. For example, a Dai Jinhua essay on the visuality of spatial transformation in contemporary China (41) is a good starting point for thinking through the everyday impacts of globalisation as they play out on public space itself. I can easily find other texts on art history or on visual methods, translated from English into Chinese, at any rate much more readily available than works by Chinese scholars translated into English in Australian university libraries. In any case, as an educator I am engaged in a constant process of translation, interpretation, and improvisation.

This is the point of expansion of regional biennales and triennales (42) and the rapid emergence of Hong Kong as one of the three main centres (after London and New York) of the global art auction market—even while the local ecology supporting artists is still very weak and artists themselves are economically incidental to these developments. In 2008, the first ArtHK art fair opens (43) and the event is sold to Art Basel in 2011. The emergence of art fairs, established by event management companies, impacts on local art by suffocating much of its air supply, evacuating local sales through galleries and funneling collectors through fairs.

Hong Kong mall, 2007; photo: Helen Grace.

Except in Hong Kong, where a rush of big-name global galleries move in, renovating warehouse spaces on a scale probably not seen since the sixties in Manhattan (44). Ironically, it is the global financial crisis of 2007-08 itself that benefits the art market in East Asia, with massive inflow of capital as a result of quantitative easing policies in the US, at the same time that China is also stimulating its economy. How sustainable any of this is remains to be seen. But a telling impact of the global financial crisis was that by early 2009 we, the scholars and educators, found many of the applicants for the support jobs that were generated by our own expansion of programs came from the financial industries, seeking to escape into what they thought were more ethical jobs in education and the arts, although these jobs were lower paid (45). This anecdote underlines one of the main differences between teaching in Australia and teaching in Asia. The first of the university restructures I experienced in Australia eliminated support jobs, sweeping through administrative levels, while leaving academic jobs untouched. All this was done in the interests of greater rationalisation and efficiency, leaving highly paid academics to do their own administration—an immediate inefficiency, since it reduced the time academics had to perform the highly specialised jobs they were being paid to do—while the management strata pretended that those administrative tasks were simple, or not even jobs, and acted as if they didn’t exist in any real space and hence required no time.

In Hong Kong, the rapid expansion of the tertiary sector and the increase in student numbers for our programs was enabled by having great support staff, allowing us to focus better on teaching, program development, research projects and consultancies: all the things we needed to do to make those jobs possible in the circularity of relations and circulation of energies. A second key difference between Australia and Hong Kong was that there were fewer meetings and consultation processes in my experience of the latter. Although this meant that upper-level management was much more opaque and undemocratic, running a bit like a triad society (lots of freedom but no democracy), in the end it seemed to work better than the ‘fake democracy’ of endless meetings that I had lived through for fifteen years in Australia (lots of democracy but no freedom).

The greater globalisation of education that moves students and teachers around the world opens up the exhilaration of new cultural embraces and, it can also unsettle permanently. That very unsettlement is a gift—and also an asset—when returning to a settler society that is itself now so unsettled. Leaving or staying, there is no escaping the movement of thought in the world.

Central Star Ferry Pier, demolished late 2006; photo: Helen Grace.

Notes

(1) Walter Benjamin, Arcades Project, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 456.

(2) Meaghan Morris and Mette Hjort, ‘Introduction’ in Creativity and Academic Activism: Instituting Cultural Studies, Morris and Hjort, eds. (Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 2012), 6.

(3) Visual and Performing Arts, University of Western Sydney, Nepean, a spectral presence, one of the institutionally erased memories of Australian contemporary art, in spite of having been one of the most important schools in the country within the first decade of its existence.

(4) 余韻 Yo In: Ideas from Japan Made in Australia (ex. cat., Melbourne State College, 1981); the kanji of the title translates as ‘reverberation’—the sound of a bell after it has been struck. To avoid the shipping costs of large-scale sculpture, designs for artistic projects were sent from Japan and executed by artists, lecturers and art students in Victoria; the initiative arose from friendship between Stelarc, then living in Japan, Fujiko Nakaya, SCAN Gallery, Tokyo, Goji Hamada and Ken Scarlett, Director of Gryphon Gallery in Melbourne. The initiative was then extended in Continuum ’83: The 1st Exhibition of Australian Contemporary Art in Japan, 22 August – 3 September 1983. (ex. cat., Sydney: Japan-Australia Cultural & Art Exchange Committee, Visual Arts Board, Australia Council for the Arts); and in Continuum ’85 = Konteniumu: Aspects of Japanese Art Today, 10–27 September 1985 (ex. cat., Sydney: Japan-Australia Cultural & Art Exchange Committee, Visual Arts Board, Australia Council for the Arts). For a recent useful summary of Japan-Australia cultural exchanges see Allison Holland, ‘Innovation, Art Practice and Japan–Australia Cultural Exchange during the 1970s and 1980s’, Asia Pacific Journal of Arts and Cultural Management 9:1 (2012) 24-31.

(5) Pamela Zeplin, ‘The ARX experiment, Perth, 1987-1999: Communities, Controversy and Regionality’, ACUADS Conference Proceedings, 2005.

(6) Fujita notes: ‘The material of the work is “soil”, which is kneaded by hand, pushed little by little while pushing with a finger. By combining the earth and the various natural environments that support it, and the contact points between them and my modeling, if the image is enlarged, it will become one rising sculpture image. The earth contains all important histories and I wish to grow the work there just like trees and grass’ food. … This is a field burn. … it can be said that it is a festival to be shown to the earth. While touching “my soil” by hand while checking my own existence, making it. And at the time of beautiful purification called “fire”, I want to look at the ash mass that will be born again in the ashes.’ (Translated from Japanese, accessed 9 March 9 2017). Unhappily the red gum burn temperature wasn’t high enough, so the work cracked, fell apart and was destroyed. But the image of its emergence on that cold morning 27 years ago is still an exhilarating thing.

(7) And in particular her situational performance work, first undertaken in West Africa in 1966-67 and continued in Australia until 1972. See Tim Johnson, ‘An Impossible Vision: Conceptual Art in the ’70s’, On The Beach, 13 (1988).

(8) Head of School, David Hull, is supportive of the general outward-looking attitude of the Faculty at that time. Anne Graham, Debra Porch, Chai-Hiang Cheo, Jacqueline Clayton, Campbell Gray and Donald Fitzpatrick are also key figures in this expansiveness.

(9) Thai-Australian Cultural Space, National Gallery, Bangkok, May 1993. Artists: Lucas and Grounds, Montien Boonma, Vichoke Mukdamanee and Kamoi Phaosavasdi. This exhibition was also shown in Chiang Mai in October 1993 and at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in May 1994.

(10) Debra Porch undertakes a residency at Hanoi Fine Art College in 1996.

(11) In 1993, in an outline that describes the then typical Australian universities and art schools’ history/theory program, we summarise our Art History and Criticism degree offerings in this way: ‘The course concentrates on the period 1750 to the present. It examines the role of criticism, the art audience, the birth and death of the avant-garde and the meanings and methods of modernism and postmodernism. Other areas covered include subjects in non-Western art, art and everyday life, and the history of architecture. The core program is augmented with a series of elective units, which in past years have included topics in theatre and architecture, Aboriginal Art, Mannerism, Soviet Culture, Museum Studies, and Australian Art.’

(12) And besides, staff are still completing PhDs—probably the last group to get academic jobs without prior PhD completion. Today, postgraduates are more likely to get internships than jobs.

(13) McCaughey had just returned to Australia to become the first Professor of Fine Arts at Monash University after a year in New York on a Harkness Fellowship.

(14) Patrick McCaughey, ‘Signs of a power struggle for the fine arts in Australia’, Melbourne Age, 29 January 1972, 15; reproduced in CAS Broadsheet, NSW, March 1972.

(15) Tim Dodd, ‘Philanthropist Judith Neilson gives $6m to UNSW to spur research into contemporary Chinese art’, Australian Financial Review, 14 February 2017.

(16) The Power Bequest, worth an estimated £A2M in 1961, was intended to establish a university department, a gallery of contemporary art (White Rabbit is already an impressive gallery of contemporary art) and a research library. See ‘Power, John Joseph Wardell (1881–1943)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, accessed 20 February 2017. Based on CPI figures, £A2m in 1961 is today worth around AU$54M. If, however, we regard that £A2M in 1961 as a Sydney house, today it would be worth AU$240M.

(17) cited in McCaughey (1972).

(18) Olivier Krischer and Stephen H. Whiteman, ‘The State of Play in Asian Art Research in Australia and New Zealand’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 16:2 (2016) 123-133. This is the first ever issue of the journal dedicated to Asian art.

(19) Roberto Fernández Retamar, Caliban and Other Essays (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 16.

(20) Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act 1, Scene 2; Caliban is played in this case by a young Joel Edgerton, approaching the role even then as a consummate professional, seeking the psychology of the character and his experience – communicating this to the students with all the force that is now his signature.

(21) Six Contemporary Chinese Artists, Space YZ, University of Western Sydney, Nepean, Kingswood Campus, 9–20 November 1992; artists: Guan Wei關偉, Ah Xian 阿仙, Ren Hua, Shen Shaomin沈少民, Tang Song唐宋, Xiao Lu肖魯. Space YZ curator: Cheo Chai-Hiang; catalogue editor, Melissa Chiu, and translator, Archibald McKenzie. The show comes out of a conversation between McKenzie and VAPA Dean, David Hull. The exhibition is roughly contemporaneous with New Art from China: Post-Mao Product, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 29 September – 25 October 1992; curator Claire Roberts (羅清奇); artists: He Jianguo(何建國), Chen Haiyan(陳海燕), Xu Hong(徐虹), Xu Bing (徐冰), Ni Haifeng (倪海峰), Fang Lijun(方力鈞), and Lu Shengzhong(呂勝中); with the show touring to the Queensland Art Gallery, Art Gallery of Ballarat and Canberra School of Art Gallery in 1993.

(22) The costumes came from the Theatre Department and had been used in a recent production of Therese Radic’s Madame Mao, first produced in Melbourne by Playbox Theatre and Circus Oz in 1986 and taken by Theatre Nepean to the US in 1990 for the International Theater Training Program, University of Wisconsin. ‘Our staging was not traditional´highly physical in all scenes. The pack of objects we traveled with, that became a malleable set, were custom crafted and designed by John Studholme as the whole project couldn’t afford any other approach.’ Yana Taylor, text message to the author, 2 March 2017.

(23) Piles of these could be bought from Bob Gould’s Book Arcade in Newtown.

(24) Mao Goes Pop: China Post 1989, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 1 June – 15 August 1993, guest curated by Chang Tsong-zung and Li Xianting; the show is a smaller version of the exhibition, China’s New Art, Post 1989 , shown at the Hong Kong Arts Centre in February 1993 and subsequently touring to Melbourne, Vancouver and five venues in the US.

(25) On the work done to make this possible, see Lisa Chandler, ‘A Project Waiting to be Done: The Legitimisation of Contemporary Asian Art within the Queensland Art Gallery’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 16:2 (2016) 185-201.

(26) The ACCF is a bureaucratic body, established in 2003 by the Home Affairs Bureau of the Hong Kong Government to promote ‘regional cultural co-operation’—parallel to APEC (Asian Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum).

(27) South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore—and mainland China of course.

(28) There are concurrent conferences on architecture, education, Asian civilisation and culture, new media arts.

(29) ACCF ministerial meetings continue but are now smaller, much more official and with less public engagement. The ‘Open Forum’ section ceased to be a part of the meetings in 2011.

(30) Foster and Partners, Design Précis, West Kowloon Cultural District, n.d., 23.

(31) ‘… visual culture includes not only visual art (such as installation, painting, photography and sculpture), but also architecture, design (such as fashion, graphic and product design), moving image (such as film, television and video) and popular culture (such as advertising and comics).’ Minutes of Subcommittee on West Kowloon Cultural District Development, ‘Progress of the West Kowloon Cultural District Project’, December 2006.

(32) The main Fine Arts Department at this point is at Chinese University of Hong Kong. There is a fee-paying Hong Kong Art School, which has a relation with Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, and the Academy of Visual Art at Hong Kong Baptist University formally comes into existence in early 2006, though classes had been taking place in the Kai Tak campus earlier than this.

(33) For a general account of the phenomenon, see, Andrew Ross, ‘The Rise of the Global University’ in Edufactory Collective (eds), Toward a Global Autonomous University: Cognitive Labor, The Production of Knowledge and the Exodus from the Education Factory (New York: Autonomedia, 2009), 18-31.

(34) For a more developed account, see Aihwa Ong and Stephen J Collier (eds), Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics and Ethics as Anthropological Problems (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005). In particular, see Kris Olds and Nigel Thrift, ‘Cultures on the Brink: ‘Reengineering the Soul of Capitalism – on a Global Scale’, 270-290; and Aihwa Ong, ‘Ecologies of Expertise: Assembling Flows, Managing Citizenship’, 337-353

(35) Susan Buck-Morss, ‘Visual Studies and Global Imagination’, Papers of Surrealism, 2 (2004).

(36) ibid.

(37) ibid.

(38) See Helen Grace, ‘Monuments and the Face of Time: Distortions of Scale and Asynchrony in Postcolonial Hong Kong’, Postcolonial Studies, 10:4 (2007), 467-483. The Central Star Ferry pier campaigns and their visuality lead me to broader research on ubiquitous media in Hong Kong. See Helen Grace, Culture, Aesthetics and Affect in Ubiquitous Media: The Prosaic Image (Oxford: Routledge, 2014).

(39) For background on the complexities of language and the diversity of Chinese ethnicity, see Evans Chan, ‘Postmodernity, Han Normativity, and Hong Kong Cinema’, in Esther M.K. Cheung, Gina Marchetti and Esther C.M. Yau (eds), A Companion to Hong Kong Cinema (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015), 207-224.

(40) If the subject of knowledge being imparted is considered ‘universal’ (such as science and engineering), the language of instruction is required to be English; if the subject of knowledge being imparted is ‘national’ (history, literature), the language of instruction is Putonghua/Mandarin and if the subject is ‘local’ (cultural studies, education? Social work?) the language of instruction is Cantonese. In practice, walking past open classrooms, everything seems to happen in Cantonese, but the PowerPoints are a mixture of English and Chinese.

(41) Dai Jinhua, ‘Invisible Writing: The Politics of Mass Culture in the 1990s’, in Jing Wang and Tani E Barlow (eds), Cinema and Desire: Feminist Marxism and Cultural Politics in the Work of Dai Jinhua (London & New York: Verso, 2002); Chinese version: Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 中國現代文學 , 11:1 (1999), 31-60.

(42) Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner (eds), Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions: Connectivities and World-making, (Canberra: Asian Studies Series Monograph 6, ANU Press, 2014).

(43) with Lehman Brothers as main sponsor, just a few months before the global financial crisis (signaled, in fact, by the collapse of Lehman Brothers itself).

(44) Living in Hong Kong is to see acutely and at close hand how the global art market works today. Australians who still look to Europe and North America for this experience overlook the extent that the world has changed. This is clear, especially at Art Basel Hong Kong, when packs of Australian collectors arrive. In the past, they would have been the buyers of contemporary Australian art—now massively undervalued, but never an ‘emerging market’.

(45) As we found in research we did for the Central Policy Unit, Hong Kong Government in 2009-10. (Study on the Manpower Situation and Needs of the Arts and Cultural Sector in Hong Kong: Final Report, Centre for Culture and Development CUHK, Policy 21 Limited, June 2012).

About the contributor

Helen Grace (b Gunditjmara Country) is an artist, writer and teacher.