Performing geographies: Asia TOPA arrives in Melbourne

Sophia Cai

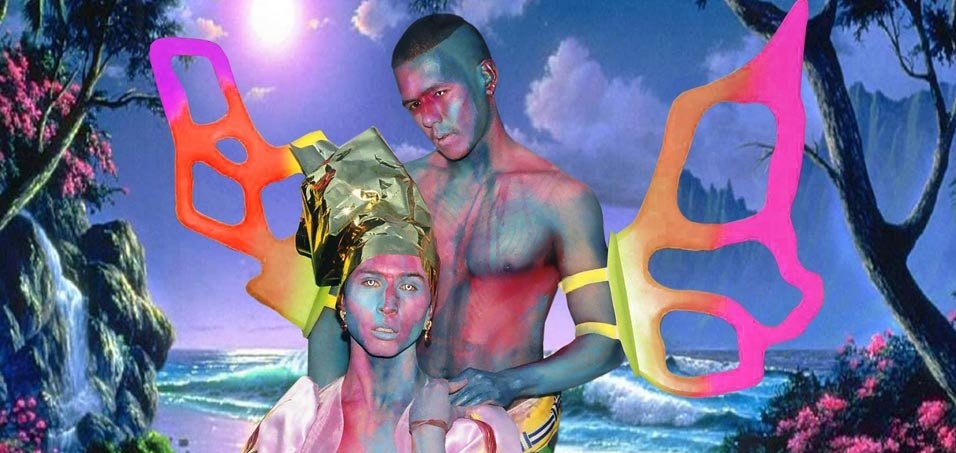

Justin Shoulder and Bhenji Ra, Club Ate, 2015, ASIA TOPA; photo: Jack Mannix, courtesy the artists.

What does a communist propaganda ballet, a night of storytelling centred on ghost stories, and an underground club celebrating queer Filipino identities share in common? They were amongst the varied programs presented as part of the inaugural Asia TOPA festival (Asia-Pacific Triennial of Performing Arts) that launched in the first quarter of 2017 in Melbourne.

Asia TOPA emerged within Melbourne’s arts calendar with what seemed like collective anticipation and curiosity within the local and national scene. The ambitious festival included over 60 events from 16 countries, and was held over a period of four months and hosted by more than 20 major cultural institutions across the city and a number in regional Victoria. It was difficult to be an arts goer during these months and not encounter at least some part of the festival (and its attendant visible branding and commercial advertising), which sought to ‘celebrate Australia’s connections with contemporary Asia’ through cultural engagement and collaborative approaches (1). Asia TOPA presents itself as a confident new festival, one that seeks to celebrate and showcase the next generation of artists from our local neighbours.

Some early highlights in the program included Climax of the Next Scene at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), a unique video triptych work by Jisun Kim situated within the virtual worlds of Minecraft and Grand Theft Auto. Kim’s work weaves philosophical enquiries with the recognisable footage from these blockbuster video-game worlds and interactions, posing larger metaphysical questions about human existence and contemporary life. Across the Yarra River, He An’s installation Do You Think You Can Help Her Brother on the exterior of the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) brought a slice of Beijing’s urban landscape to Melbourne. The installation, which consisted of more than 50 Chinese characters in the form of found neon signs, lit up the side of the building with a poetic poignancy. Both Kim and He’s contributions emphasised the individual experience of people from within bustling contemporary metropolises, and highlighted some of the impressive international artists under the festival’s fold.

While these early events were notable, it is perhaps easy to cast a cynical eye over the breadth and length of a cultural festival like Asia TOPA, which sets such an ambitious agenda based on an arguably contentious cultural and geographical categorisation of the Asia-Pacific. Programming that attempts to chart the diversity and breadth of multiple creative disciplines and histories faces an enormous task at the risk of simplification and tokenism. Early criticisms of the festival within local artist circles focused on the perceived invisibility of local Asian-Australian representation in the triennial, as well as concerns surrounding the arms-lengths engagement with a program that at times lacked focus or critical engagement with existing dialogues or audiences.

The Red Detachment of Women, a National Ballet of China production presented by Arts Centre Melbourne in association with The Australian Ballet and Orchestra Victoria for Asia TOPA 2017. Photo: Mark Gambino. Image courtesy National Ballet of China and Asia TOPA

While these early events were notable, it is perhaps easy to cast a cynical eye over the breadth and length of a cultural festival like Asia TOPA, which sets such an ambitious agenda based on an arguably contentious cultural and geographical categorisation of the Asia-Pacific.

It must be noted that Asia TOPA is certainly not the first pan-Asia program of its type to be held in Australia. Since 1993, Brisbane has been home to the long-running and widely acclaimed Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) as well as the BrisAsia Festival, which launched in 2013, while Adelaide has been a home to the OzAsia festival since 2007. In fact, the creative director of Asia TOPA Stephen Armstrong identifies the APT as the ‘blueprint’ for the inaugural triennial. In this way, the artistic goals of Asia TOPA and its presentation in Melbourne are perhaps not new territory; but how can it be understood or situated against Melbourne’s broader cultural scene and engagement with our Asia-Pacific neighbours?

Melbourne’s cultural sector, like that of Australia’s broader arts sector, suffers from a known and identified diversity problem. Recent studies of Australian artists show that only 8% of professional artists are from a non-English speaking background, while in the general population this number doubles to 16% (2). In media interviews with Stephen Armstrong he outlines the festival’s goals to redress the lack of cultural diversity on our stages, and to bring Asian performing arts out of its ‘niche programming strand’ (3). Asia TOPA’s associate director Kate Ben-Tovim similarly discusses the motivation of the triennial to normalise Asian cultural experiences and remove barriers (4). In this way, while a focus on multicultural art engagement is not new, we can certainly applaud Asia TOPA for its highly visible intervention in this regard.

The issue with this type of engagement based on addressing diversity is that it is still framed within the very structures from which it emerges. As a festival instigated by key partners from the Arts Centre and with principal sponsorship of $2m by the Sidney Myer fund, Asia TOPA undoubtedly catered more strongly towards a certain artistic vision centred on the performative body, and more specifically the body as a representation of social commentary and cultural representation. Much of the program addressed the topic of cultural diversity through the corporeal representation of young Asian bodies and flesh.

This focus on the Asian body was felt strongly in headlining programs such as The Red Detachment of Women, a ballet from China’s more fervent communist era shown in Australia for the first time at the Arts Centre Melbourne. The ballet tells the story of a young peasant woman who escapes her tormentors and rises through the ranks of the Red Detachment, a women’s only military arm of the Communist Party, and ultimately leads to the liberation of the people. The Red Detachment is a striking piece of visual propaganda, a time-capsule from a contentious period of Chinese modern history re-staged for contemporary audiences. I went to this performance with my mother who grew up in China during the 1960s when the ballet was initially developed and shown as a piece of Communist propaganda, and she spoke to me afterwards of the strange nostalgia she felt hearing the score and seeing the performance again. In fact, during the performances of the ballet there were sustained protests outside the Arts Centre about this very contentious history and lineage, a point that the festival producers distanced themselves from in official statements and interviews with the press.

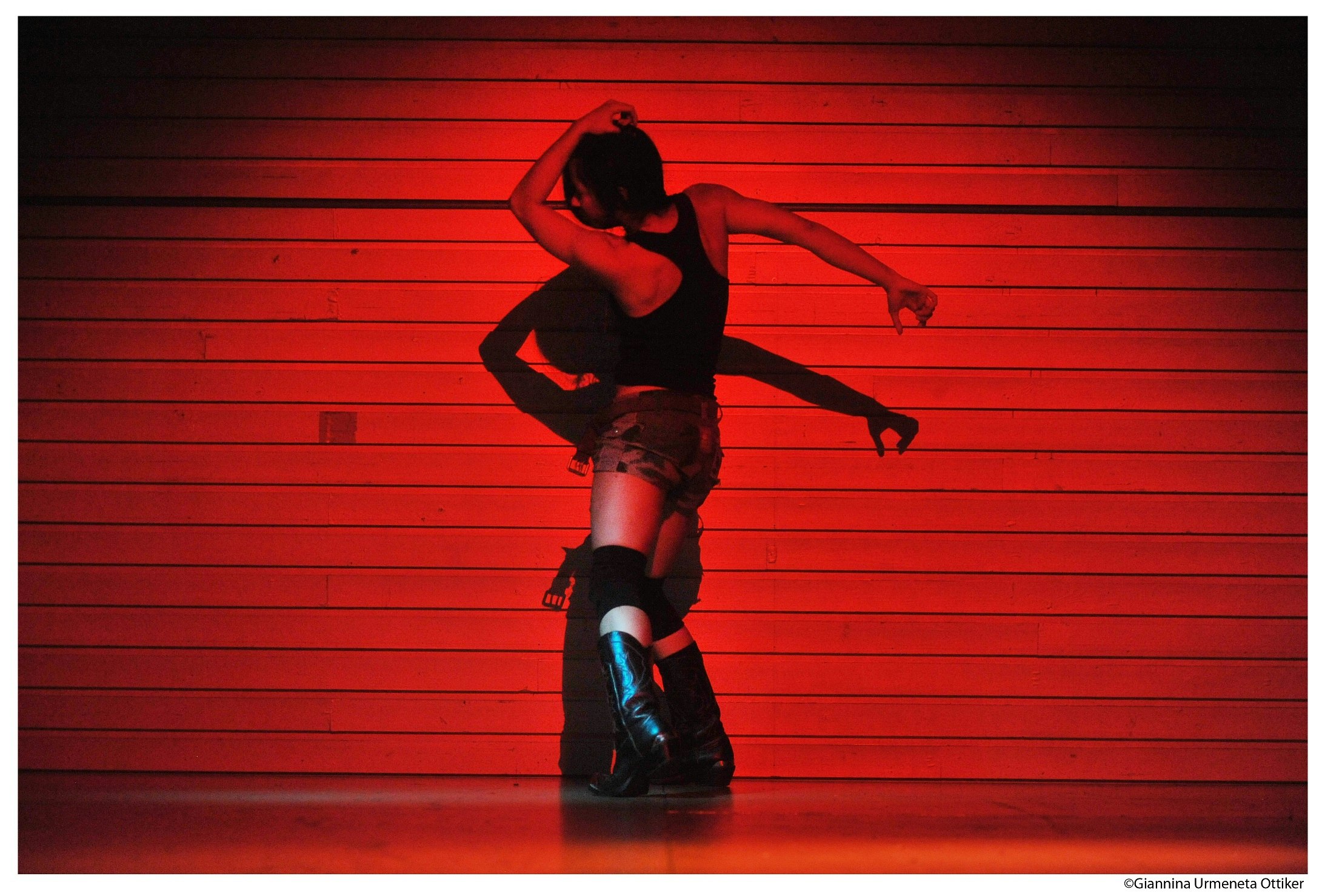

XO STATE DUSK: Macho Dancer. Concept, choreography and performance by Eisa Jocson; photo: Giannina Urmeneta Ottiker, image courtesy the artist and Asia TOPA.

More contemporary programs such as Macho Dancer at the Arts Centre, Bunny at Meat Market, and Club Ate at ACMI presented the body through the lens of seduction, desire and sexuality. These three bold programs shared a common interest in questions surrounding gender identity, charting a fluidity and ambiguity in expressions through contemporary dance and performance. Bunny and Club Ate also further blurred the lines between performer and audiences: in Bunny, themes of consent and trust were considered by inviting audience members to partake in an interactive exploration of bondage and the erotic art of shibari (5), while Club Ate brought an underground party into the institutional halls of ACMI, with a palpable sense of excitement and celebration of diasporic queer communities. In contrast to The Red Detachment, these programs felt much more contemporaneous and provocative. It highlighted one of the festival’s main strengths, which was a focus on the shifting terrains of artistic collaborations through the work of a younger generation of performers and producers.

Elsewhere, this focus on the body was also felt strongly across the visual art exhibitions Body + Cloth at the Australian Tapestry Workshop in the city’s south, as well as the exhibition of performance art at Arts Centre in Political Acts. The inclusion of the Tapestry Workshop as a partner venue and the exhibition’s focus on textiles and cloth offered an intriguing departure point from the more performance-focused documentation shown in Political Acts. Together, both these exhibitions considered the social and political connections forged in the body as a vessel for commentary or protest. Considered within the broader discourse of Asia TOPA, the potency of physical bodies as a site or embodiment for social commentary was strongly felt.

Eugenia Lim, The People’s Currency, 2017, Federation Square, Melbourne, commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art for Asia TOPA 2017; photo: Zan Wimberley, image courtesy the artist.

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art presented two new performance works for Asia TOPA that further engaged with the bodily to consider issues related to currency, labour and the economy. Abdullah M. I. Syed’s Flying Buck Exchange performance series saw the artist distribute, exchange and literally consume money. The US dollar is a potent symbol for the navigation of the global market, and Syed’s consumption of the notes are a playful yet confronting look at our own obsession with monetary profits and loss. Eugenia Lim’s The People’s Currency similarly considered our relationship with consumption and capitalism. Dressed in a reflective gold suit, Lim invited audience participants to enter into a short-term employment contract with her ‘factory’ (a shipping container parked at Federation Square) for remuneration in the form of artist-produced currency. As a work of endurance performance, the success of Lim’s works resided in her ability to transform convincingly into the role of the ‘Ambassador’ and to engage with audiences.

One of the notable highlights of Asia TOPA was an elusive one-night performance at ACCA that brought together notable indigenous and Pacific Islander collaborators, Lukautim Solwara (look out for the ocean). As a collaboration with Next Wave Festival, Lukautim did not fail to disappoint eager attendees who were inducted into a transformative night of performance, art and dance within the halls of ACCA amongst the institution’s concurrent exhibition, Sovereignty. Led by artist Rosanna Raymond, the performers in this work considered the living legacies of ancestral cultures and ceremonies. They moved freely through the galleries, while audiences were encouraged to roam during the performance, creating a wholly immersive and responsive experience. Lukautim added a much needed dialogue surrounding Indigeneity to the festival, but it also provided an encounter between audience and performer that challenged the experiences of a ‘white cube’ gallery. The open-endedness of the performances and the roaming nature of the work ensured that no two encounters were the same.

Rosanna Raymond with collaborators Leuli Eshraghi, Amrita Hepi, Thomas ES Kelly, Nicole Monks, Steven Rhall, Reina Sutton and Jaimie Waititi, Lukautim Solwara (look out for the ocean), 2017, commissioned by Next Wave and Arts Centre Melbourne for Asia TOPA 2017; photo: Sarah Walker, image courtesy the artists and Asia TOPA.

While the strength of individual programs is true—and as a reviewer I certainly held a bias in my selection of programs based on peer recommendations—the enjoyment of these events were underscored by a broader examinations of Asia TOPA’s goals and successes. When considered as a whole, it could be starkly felt that Asia TOPA lacked a critical engagement or a unifying artistic vision. Although the festival did offer a selection of ‘curated journeys’ on its website and brochure, this was really a hand-picked selection of key programs (and potentially, key partners) that excluded as much as it included. This may have been due to the fact that under the festival’s gamut, individual organisations were provided with invitations or funding (or both) to devise and deliver their own programs, thereby not prescribing or answering to one singular theme. This devolved style of programming is perhaps not necessarily a bad thing, as it allows for the individual strengths and nuances of the presenting organisations and artists to show through. However, it may have been worthwhile to see some of the themes presented in these curated selections extended to the rest of the festival, or to have these links more strongly felt. At the very least, this sort of cohesion could have helped establish more dialogues and exchanges between programs, institutions and diverse art forms.

At times, the link or critical engagement with Asia in what is ostensibly a major show of force in Asia-focussed arts programming seemed strenuous. This was particularly felt in programs that moved away from the performance-centric focus of the festival. I attended the Boiler Room Lecture at the State Library with Mami Kataoka, the chief curator of the Mori Art Museum and the artistic director of the forthcoming 21st Biennale of Sydney. Kataoka’s talk offered an illuminating discussion of her curatorial practice, with particular focus on her international projects, and gave some insights into her future plans for Sydney. When Kataoka’s Biennale post was first announced many celebrated that she was to be the first Asian curator at the helm since its inception more than 30 years ago. Bringing Katoako into Asia TOPA’s fold was a significant opportunity to hear from this international curator, but it did lead one to wonder about the talk’s connection with the rest of the performing arts festival. Katoaka is not a performance curator, and in fact, her curatorial vision resisted readings or delineations of Asia specificity. Her talk, while illuminating, made no reference to Asia TOPA and her place within it. Was Katoaka’s inclusion in the festival simply an attempt to add criticality and curatorial ethos to the program?

Dancer and choreographer Pichet Klunchun at The Wheeler Centre Gala 2017: Stories for the Dead, presented in partnership with Arts Centre Melbourne for Asia TOPA; photo: Jon Tjhia, image courtesy The Wheeler Centre.

I similarly felt strange sentiments about the inclusion of the 2017 Wheeler Centre Gala as part of Asia TOPA at the Arts House. Like previous Wheeler Centre programs in this vein, this was a night of storytelling featuring an ensemble of readings and performances by writers, poets, musicians and others who work the spoken word. The theme of this year’s gala was ‘stories for the dead’ and the guests covered diverse approaches to the theme ranging from poignant to humorous. The Wheeler Centre’s program is well-known for their selection of diverse speakers, not only from the literary field but also spanning academics and media personalities, and this night was no exception. While it was true that the program included many Asia-Pacific guests, the headlining acts remained US-based musician and author Amanda Palmer as well as local broadcaster Myf Warhust and journalist and writer Clementine Ford. As an evening of engaging storytelling, the gala was a success, but as a key program of the Asia TOPA festival, the inclusion was a strange choice—I doubt few can deny that the gala could have easily been presented as part of any of Melbourne’s other cultural festivals that litter annual calendars.

These issues raise a principal question regarding Asia TOPA’s program selection and its strategic choices: how can a festival nominally about performing art reach a wider cultural audiences while forging deeper conversations around Australia’s relationship with Asia? It felt at times that Asia TOPA was trying to have its cake and eat it too, focussing on narratives and bodies from the Asia-Pacific, yet still framing and presenting this in a way catered to Australian (which is to say, majority white Australian) audiences and expectations. This disingenuous engagement was felt particularly when considering the festival’s marketing, which heralded each performers’ particular geographical origins in the brochures and their blurbs, even when the works in question did not explicitly refer to this context or social connection, or much less appear particularly informed by such a territorially defined paradigm at all. This obsession with geographical difference was also felt in the audience surveys (I completed one at ACCA) which asked questions along the lines of ‘how did this performance engage your knowledge of this cultural group?’ (6). This survey implied that audiences stood at a distance from the experiences of the performers, an observer gazing upon ‘otherness’ in a way that felt strangely out-dated.

It felt at times that Asia TOPA was trying to have its cake and eat it too, focussing on narratives and bodies from the Asia-Pacific, yet still framing and presenting this in a way catered to Australian (which is to say, majority white Australian) audiences and expectations.

That being said, I am trying to resist being too critical of Asia TOPA simply because I can appreciate the significance of staging programming like this in Melbourne. The city has long viewed itself as the cultural capital of Australia, and Asia TOPA is certainly a festival that brings together talented performers and significant arts organisations to consider the ongoing relationship between Australia and the Asia-Pacific. As a curator, I was emboldened by the festival’s varied programs that offered new encounters and experiences across art forms presented at spaces and organisations I’d otherwise not usually visit. That such discussions around representation and cultural engagement within artistic realms, much less across the broader pop cultural sphere, are easily subsumed into ‘vital’ and ‘timely’ categories of necessity demonstrates the ongoing issues surrounding the representation (or lack thereof) of criticality in Asian perspectives amongst Australian audiences. How can we step outside the Euro-centric gaze (even as Asian-Australians) to consider diversity in a manner that is not tokenistic or stereotyped?

What will be critical to see is how the next iteration of Asia TOPA develops as well as delivers, and how the collaborations and relationships established through the current program inform the next festival. It would be encouraging for audiences and local artists alike to witness a vast increase in opportunities to have these programs and artistic voices present across all art and all culture all of the time without the need for the ‘Asia’ delineation that might suit the bureaucratic terms of government while directly contravened by the sheer ordinariness of true Australian cultural diversity witnessed in everyday life. Conversations around Asian art are still often framed by historical and social commentary, linked to countries of origin as a point of distinction from narratives of Western art history, and so it will be interesting to see how these conversations continue to shift around globalised art practices and movements of artists. For myself, the highlights are in the slippages—those moments of in-betweeness, such as seen in Lukautim Solwara, where in the juncture between two parts a new, third space is created. To embrace these slippages may require a more self-reflexive approach, one not structured by definitions nor place markers on a map but rather allusions that signal who we already know ourselves to be.

Asia TOPA: Asia-Pacific Triennial of Performing Arts, January – April 2017

Notes

(1) Statement taken from https://www.asiatopa.com.au/ (accessed 29 March 2017).

(2) Ien Ang, ‘Australia’s art community has a diversity problem – that’s our loss’ in The Conversation, 21 January 2016 (accessed 15 March 2017).

(3) Emma Brancatisano, ‘The Asia TOPA festival is bringing Asian Performing Arts to Melbourne in 2017’ in Huffington Post, 12 December 2016 (accessed 29 March 2017).

(4) Fiona Gruber, ‘The conversation’s changed: how Asian culture edged into the Australian mainstream’ in The Guardian, 16 February 2017 (accessed 15 March 2017).

(5) Ancient Japanese artistic form of rope bondage.

(6) As the survey was a digital form, I did not have a chance to take down the exact wording and I may be misquoting here, but the sentiment remains.

About the contributor

Sophia Cai is a curator and arts writer based in Narrm/Melbourne, Australia.