Eating Bitterness: Mourning, Memory, Motherhood in the work of three Chinese Artists

Luise Guest

1. Mourning

Suddenly I’m as if cast out,

and this solitude surrounds me

as something vast and unbounded…

— Rainer Maria Rilke in Girl’s Lament

I have been having strange and vivid dreams since early 2020. Sometimes I am a child looking for my mother. Or my daughters are tiny children once again, and we are fleeing some terrible danger. Apart from the small matter of a global pandemic, my disturbed dream life is no mystery—my mother died in February, just a few weeks before the whole world shut down. For ten years before that, living in a fearful world of dementia, she sometimes asked me: “Who are you? Are you my mother? Where is my mother?”

As I work out how to mourn while the entire world seems consumed by grief and fear, the subject of mothers and daughters occupies my mind. Long ago, in rural China, illiterate village women in Hunan Province invented a slanted script to write their stories of loss and bitterness. Nüshu—a syllabary, not a language, and no secret despite the romantic myths that have grown up around it—was a vehicle to communicate gendered hardships that would otherwise be unrecorded and unremembered. Bridal laments—or kuge (crying songs), stylised performances of grief sung at weddings as girls prepared to leave their natal families forever—became a female canon of lamentation. (1)

I find myself wishing for such a convention of sorrow. Denied consolatory rituals of mourning by Covid-19, I am at a loss. A funeral with only myself and my daughters in attendance, a larger gathering to celebrate her life and scatter her ashes indefinitely postponed, has left me in a kind of limbo. Drifting through months of sadness, trying to summon up the will to write, I turned to my various conversations with other women on the subject of daughters, mothers and grandmothers.

2. Memory

Through this time of closed borders and lockdowns, I revisit my interviews with women artists in China over the last decade. Since I cannot return to China, I have conducted new interviews in the virtual realm. I’ve also been reading old transcripts and listening to conversations recorded in two languages, always punctuated by the sound of pouring tea, ringing phones, and the ubiquitous barking dogs that wander around the artists’ villages in Beijing. I am struck by how often these conversations turn to difficult memories of primal maternal relationships.

I have talked with daughters whose parents were bitterly disappointed they were not sons; with daughters separated from mothers imprisoned or exiled during the anti-rightist campaigns; with mothers who desperately wanted more than the one permitted child, and with younger women pressured by mothers who were denied their own education during the Cultural Revolution. These are complicated matrilineal connections, ruptured by political history, social change and patriarchal systems of power and patronage. Women born at the start of the Cultural Revolution experienced the untethering of their own mothers from Confucian-inflected ideals of ‘the good mother’. A generation of younger women, products of the One Child Policy, are now being pressured to have two children: women’s fertility is still controlled by the patriarchal state, and it seems they are still required to ‘eat bitterness’. (2)

What it means to be a mother, or to be a daughter, is continually reinvented. My recent conversations with three artists reveal how they navigate the emotional fallout, and how their work interrogates notions of gender.

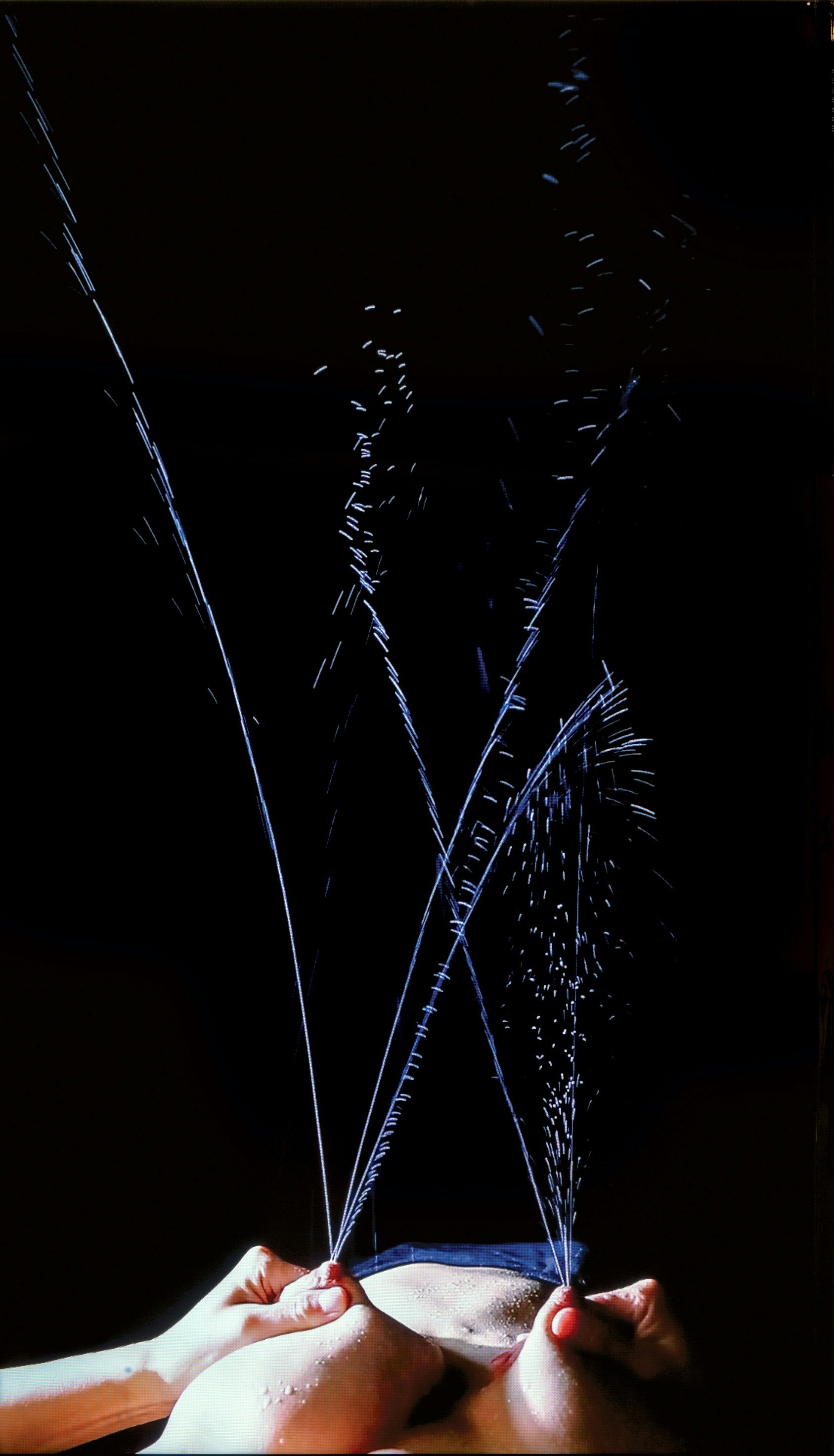

Cao Yu, Fountain, 2015, single channel HD video (colour, silence), 11’10’’edition of 10 + 2 AP; image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne

3. Motherhood: Eating Bitterness

In my conversation with Cao Yu via WeChat and email, we spoke about the video work that made her notorious in Beijing. Shown at her Central Academy of Fine Arts graduation exhibition, Cao’s video Fountain (2015) is shot from her own point of view as she looks down at her lactating body. At the bottom of a vertical video screen, in dramatic chiaroscuro, jets of milk spurt into the air as the artist’s hands rhythmically squeeze her breasts. It’s aesthetically beautiful, visceral, funny—and very subversive. With its title alluding to Marcel Duchamp’s iconoclastic readymade (a porcelain urinal turned on its side) and to a 1966-7 work by Bruce Nauman (showing the American conceptual artist spitting out an arc of water), Cao’s Fountain deflates the phallic conceits of the two ‘seminal’ works and disrupts the male gaze.

Through this work, Cao makes us see new motherhood as a strange combination of exhaustion and exhilaration. At the time, the artist was suffering from mastitis, which causes high fevers and unbearable pain, so to express her milk was both excruciating and an exquisite relief. But Cao was also newly aware of the power of the female body; her breasts, she says, were like active volcanoes: “I felt for the first time as a woman that my body could have an even more violent power to release tension than a man’s.” (3)

Cao Yu, Everything is Left Behind, 2019, canvas, fallen long hair (the artist’s), h.135cm, w.90 cm; courtesy artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne

Everything is Left Behind (2019) undercuts that sense of female power with explicit references to how girls and women are valued. White canvases are embroidered with sayings that reveal deep-seated cultural beliefs about women; the thread is Cao’s own long black hair. The first panel begins with a quote from the artist’s father at her birth in 1988: “Alas, we are so unlucky, we gave birth to a baby girl’. Another reads: ‘If you’re not a good girl, I will abandon you.” Later works in the series emphasise parental pressure to succeed academically and also to be beautiful: “Look how fat you are, there’s never enough food for you.” In the physicality of these works—their awkward Chinese characters sutured with hair—a simmering mixture of anger and sorrow is palpable.

Cao Yu, I Have, 2017, single channel video (colour, sound) 3 edition of 6 + 2 AP; image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne

I Have (2017) examines gendered pressures more pointedly. Speaking to the camera, Cao proceeds to boast. She begins with her appearance (“I have an envy-inducing figure… I have an hourglass waist…”), her marriage (“… I have a husband who dotes on me…”) and adds: “I have a child prodigy for a son.” Cao satirises the ambition, material accumulation, consumerist desire and success of the Chinese zeitgeist: “I will have everything an artist has or could ever want…” yet to be truly successful, it seems, a woman should produce a “child prodigy for a son”. Cao also defies the expected gender performance of modesty and humility. She says, “People are unable to distinguish between genuine and fake, and what they really like to hear and see is weakness in a self-comforting way, to protect their fragile glass hearts.”

Ma Qiusha, From No. 4 Pingyuanli to No.4 Tianqiaobeili, 2007, video, 7min. 54 sec; image courtesy the artist and Beijing Commune

Ma Qiusha was born four years earlier than Cao Yu, in 1982, the year that the One Child Policy was most strictly enforced. In two conversations several years apart, she explained how her work reflects a sense of being caught between the collectivist High Socialist society of her parents, in which private ownership of property or business enterprises was non-existent, and the world of aspiration and material prosperity, in which she grew to adulthood. In the eight-minute single channel video, From No.4 Pingyuanli to No.4 Tianqiaobeili (2007), she speaks directly to the camera with increasing difficulty, recounting the punishing pressures that shaped her childhood: the sense that she was never good enough, and that she must compensate for the losses her parents experienced as casualties of the Cultural Revolution. Finally, Ma Qiusha removes a razor blade from her mouth, which is filled with blood. She told me: “I cannot really explain why I used the razor blade, except that when I returned from America. I had a bitterness in my mouth, but I had to keep smiling. There is a contrast in this work – the razor in your mouth causes physical pain but the story I am telling is about mental pain.” (4)

No. 4 Pingyuanli is the address of the public maternity hospital where she was born. During this period, the very early days of Deng Xiaoping’s ‘Reform and Opening’ policies that opened China to global markets, China was still essentially a collectivist society. No. 4 Tianqiaobeili, on the other hand, is the address of the first private apartment that her parents were able to buy. The two addresses represent the dramatic transformation of Beijing, from an old city of bicycles, buses and hutong neighbourhoods to a shiny metropolis of private cars, shopping malls and slick apartments. Ma Qiusha told me that she has spent years trying to reconcile this binary between collectivism and individualism.

All my sharpness comes from your hardness (2011) searingly communicates the loneliness of the one-child generation, driven to succeed at all costs. Ma filmed herself being dragged behind a car on the road leading from her grandmother’s house to her home. We see only her legs and feet, wearing ice skates, which scrape excruciatingly across the asphalt as she zig-zags back and forth. Ma explained in her exhibition essay: “The pavement races underfoot, grinding against the blades of the skates. The blades grow sharper and sharper, until finally, they become knives. Real knives.” (5) For a series of installations using women’s stockings, Ma collected many pairs of the thick, skin-coloured tights worn by Chinese women in the 1980s and 1990s. She stretched them over broken chunks of cement that were pieced together like a mosaic, recalling an aerial view of a landscape.

Ma Qiusha, Wonderland, 2016 (detail), cement, nylon stocking, plywood, iron, resin, h.980cm, w.615 cm; image courtesy the artist and Beijing Commune

Wonderland (2016) relates to a childhood memory. (6) Riding to school on the back of her mother’s bicycle, Ma would see women’s legs, covered like a second skin in unflattering tan tights, when they stopped at the traffic lights. The ladders in her mother’s tights revealed the flesh beneath, a hint of the softer persona beneath the harsh disciplinarian. Together with the broken shards of cement, these stockings represent China’s emergence from the Mao era, but they are also a deeply personal reflection on the bond between mother and daughter. In 2011 Ma Qiusha wrote: “Though I love my mother deeply, that love is often fraught with pain.” (7)

When Liu Xi was born in 1986, her family members expressed great disappointment at the birth of a daughter in a similar story to that of Cao Yu and Ma Qiusha. Liu’s nainai, her paternal grandmother, urged her mother to give her away so she could have one final chance at bearing a son. (Rural families in the 1980s were allowed a second child if the first was a girl). Liu told me, “Actually, my mother told me she was crying when I was born as a girl. But she never wanted to abandon me.” (8)

In Liu’s hometown of Zibo, in Shandong Province, things have not changed much: “I still hear stories from my elementary school classmates of domestic violence, of blaming themselves for having a daughter [ … ]” Because of this harsh reality, Liu reflects on the role of authority, rules and propaganda in her practice: “I perfected the scars of painful memories, sorted myself out, and forgave their ignorance. Art has a strong healing effect for me.” (9)

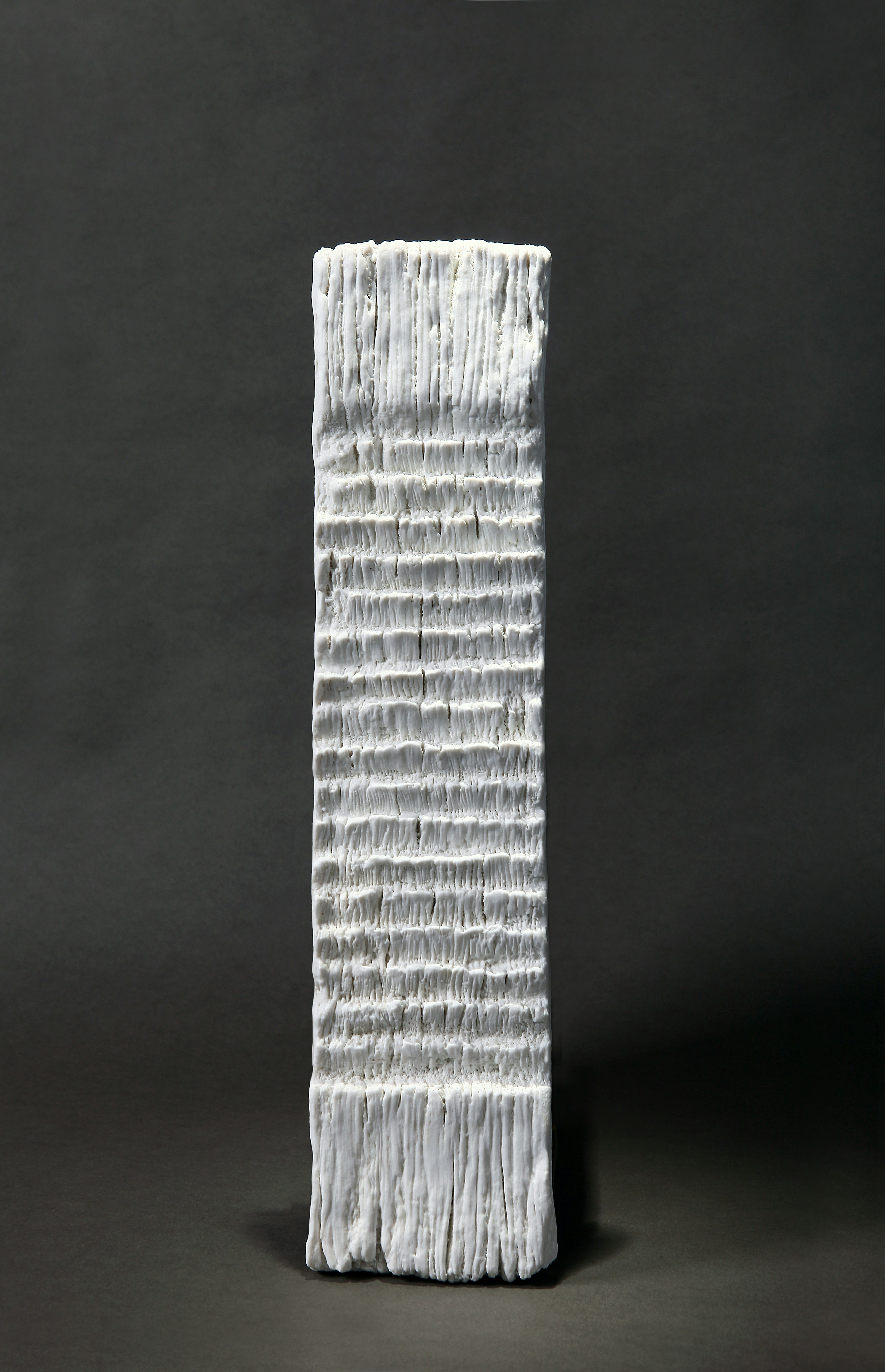

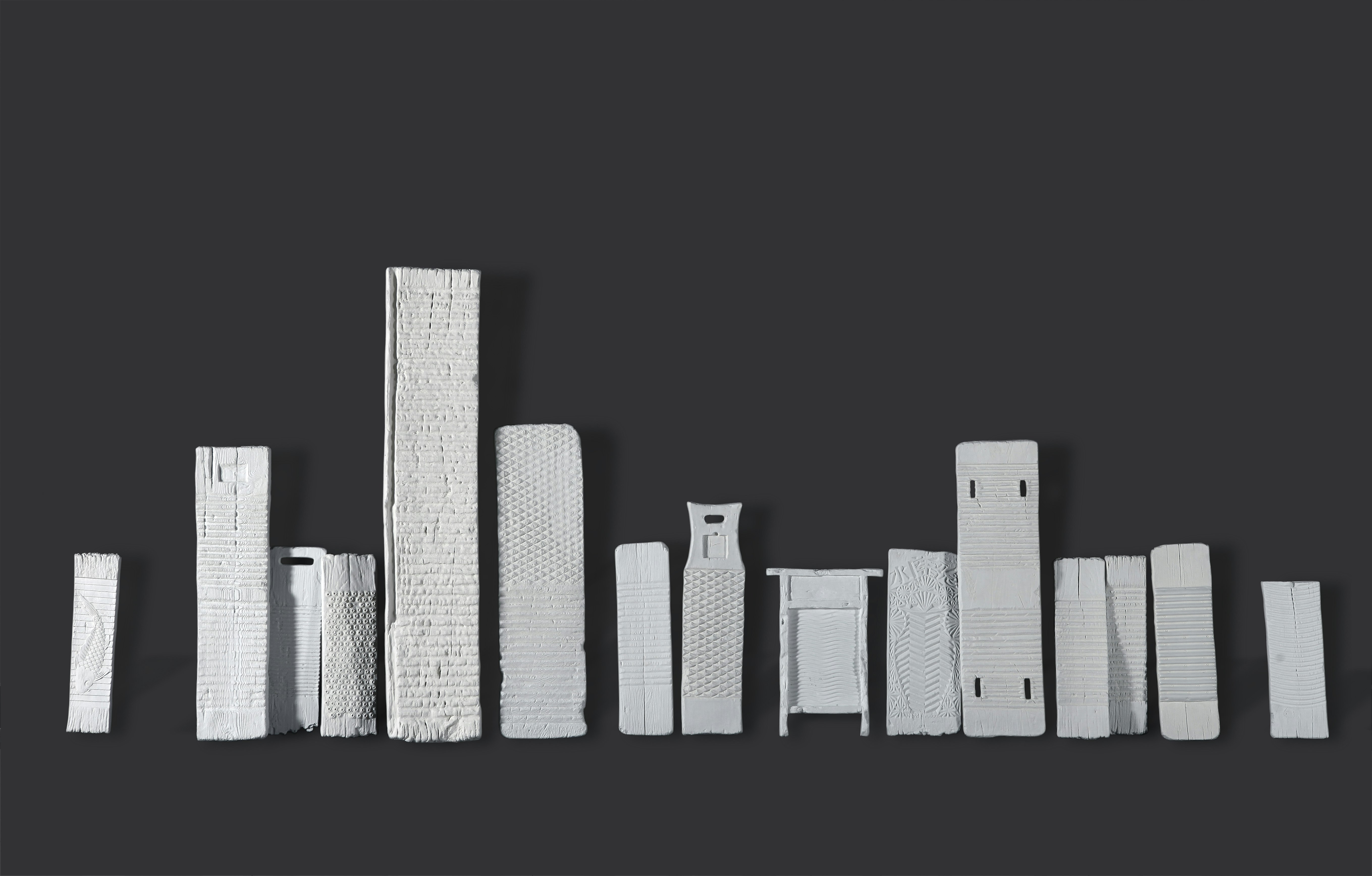

Liu Xi, MaMa, 2015-2020, porcelain, h.365cm, w.125cm, d.15cm; photo: Tao Min; courtesy the artist

Liu Xi works with porcelain in experimental and sometimes transgressive ways. Our God is Great (2018-19), an installation of 52 porcelain vaginas (or, to be more anatomically accurate, vulvae) coloured with ink, for example, confronts misogyny very directly. In her ongoing series MaMa (2020), the body is present only as a memory. Liu collected weathered wooden washboards, once commonly used in China to scrub laundry, and cast them in white porcelain, juxtaposing the highly-prized material of the imperial kilns with ‘low’ items used by rural women. These objects are as obsolete as Ma Qiusha’s collection of thick, skin-coloured tights. Liu took a washboard with her to the dormitory of Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts. It was a talisman-like memory of home, and of her mother, reminding her of: “[…] the unconditional love that my mother showed for me all those years, washing clothes, cooking, taking care of me […] The washboard she used in the past was abandoned in the corner, and when I saw this, I brought this first washboard from my mother into my porcelain world.” (10)

Liu’s mother left school at the age of nine to help support her family by working on farms and in factories; she also made papier-mâché funeral objects. It was a life shaped by poverty, prejudice and propaganda. Without an education, Liu’s parents sought a precarious, nomad-like livelihood. The MaMa series, Liu says, tells the story of a mother’s unconditional love for her child, despite everything. It also conveys her belief that adult daughters can be ‘strong pillars’ supporting and protecting their mothers, fulfilling all the same filial obligations as a son.

Cast in porcelain, the grooves and ridges that once formed the scrubbing surface of the old washboards are like an unreadable text on blank, white pages. After Liu had replicated her mother’s board in 2015, she began to collect more boards from other women throughout China. They are all different, despite their common function. Some have elaborate designs of propitious fish or flowers carved into the timber surface, while others, more utilitarian, are simply corrugated. Together, they construct an unwritten history of ordinary women and their anonymous labour. Liu says, “Women’s suffering and sacrifice are not [the] only tragedies; forgetting and neglect are the greater invisible tragedies.” (11) Leaning against the wall of the gallery, the porcelain washboards resemble memorial stelae.

A sense of aching love and loss swirls through these conversations and reveals itself in the works of each of the three artists. Their interviews echoed my sense of being adrift in a melancholy sea, focused on mother-daughter relationships that are no less powerful in memoriam. I am reminded of a gentle animated film made for children at the Shanghai Film Studios in 1960, called Where is Mama? (12) Each beautifully rendered ink-and-wash frame depicts a little group of tadpoles searching for their mother in a watery landscape, plaintively asking goldfish, shrimp, turtles, and other creatures, ‘Women de mama, zai nali / ‘Where is our mother?’ I suspect this is a question we continue to ask ourselves throughout our lives.

Notes

-

See more about the use of Nüshu by contemporary artists in Chapter 8 of my book, ‘Half the Sky’ (Piper Press, Sydney, 2016) and in two articles: Luise Guest, 2015. ‘Secrets, sorrow and the feminine subjective: Nüshu references in the work of contemporary Chinese artist Ma Yanling’, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, Vol 2 (1); Luise Guest, 2018. (In)visible ink: Outsiders at the Yaji, the ink installations of Bingyi and Tao Aimin, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, Vol 5 (2-3). Fei-Wen Liu’s ethnographic researches provide insights into the history and current status of the script, in particular her book ‘Gendered Words: Sentiments and Expression in Changing Rural China’ (Oxford University Press, 2015)

-

‘To eat bitterness’ – 吃苦 (chīkǔ) – means to endure suffering and hardship without complaint. Women, in particular, have always been expected to do this.

-

Unless otherwise acknowledged, all quotes from Cao Yu are excerpted from a Wechat/email conversation with the author that took place between April and August 2020.

-

Ma Qiusha completed an MFA at Alfred University, New York, in 2008. Unless otherwise acknowledged, all quotes from Ma Qiusha are excerpted from two recorded interviews with the author in Beijing, in 2014 and 2019.

-

From Ma Qiusha’s brief explanations about her works in the UCCA exhibition, ‘Curated by Song Dong: Ma Qiusha, Address, and Wang Shang, Sleuthing’, 2011, accessed online: 25 August 2020.

-

The ironic title refers to an unfinished amusement park outside Beijing, abandoned by its developers in the late 1990s and now demolished, a desolate memory of late twentieth- century China.

-

Curated by Song Dong Ma Qiusha: Address & Wang Shang: Sleuthing’ in Art Slant, 2011, accessed online: 25 August 2020.

-

Unless otherwise acknowledged, all quotes from Liu Xi are excerpted from Wechat/email interviews with the author in April and August 2020.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Where is Mama’ or 小蝌蚪找妈妈 (1960, Shanghai Film Studios under the guidance of Te Wei) was shown at APT 7 at QAGOMA in 2013.

About the artists

Cao Yu 曹雨 (b.1988, Liaoning) studied in the Sculpture Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, graduating with a BFA in 2011 and an MFA in 2016. Since graduation her work has been shown in China, Korea, the United States, Australia, Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Solo exhibitions include ‘I Have an Hourglass Waist’, Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing (2017) and ‘Femme Fatale’, Galerie Urs Meile, Lucerne, Switzerland (2019). Awards include Best Young Artist of the Year·The 12th AAC Award of Art China (2018); named China Art Power 100 (2018) and shortlisted for the Chinese Contemporary Art Award (CCAA); Nomination, the French Opline Prize(2019) ; Nomination, French Yishu 8· Chinese Young Artist Award(2017). Cao Yu was also selected into Gen. T China’s Top 100 New Pioneer (2020). Cao Yu lives and works in Beijing.

Ma Qiusha 马秋莎 (b. 1982, Beijing) received her BA in Digital Media Art from China Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2005 and MFA in Electronic Integrated Arts from Alfred University, New York in 2008. Solo exhibitions include ‘Tales of White Nights’, Beijing Commune (2019); Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, UK (2018); OCT Contemporary Art Terminal Xi’an, China (2018); Beijing Commune, Beijing (2016, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2009); Chinese Arts Centre, Manchester (2013); Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing (2011) and Taking Space, Beijing (2010, 2007). Her work has been shown widely internationally in curated exhibitions, including at Daimler Contemporary (Berlin); Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Los Angeles); Tai Kwun Contemporary (Hong Kong); Smart Museum of Art (Chicago); Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris); Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (Karlsruhe); Tate Modern Museum (London); Orange County Museum of Art (Orange County, US); Borusan Contemporary (Istanbul); Tampa Museum of Art (Tampa, US); Stavanger Art Museum (Norway) and more. Ma Qiusha currently lives and works in Beijing.

Liu Xi 柳溪 (b.1986, Zibo, Shandong) studied in the Sculpture Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, graduating in 2010. Liu’s innovative and experimental work in ceramics explores ideas about sexuality and gender, identity, and freedom. She has participated in exhibitions in China and internationally, including in 2019 her first solo show, ‘Earth in My Hands, Fire in My Heart’ at Art + Shanghai Gallery. Liu has participated in artist residencies in Bali, Taipei, Yixing, and Mexico. Liu Xi lives and works between Shanghai and Jingdezhen.

About the contributor

Luise Guest is an art educator, independent writer and researcher based in Sydney.