Regional synchronicities: Southeast Asia through the eyes of Valentine Willie

Mikala Tai

As I sit down to write this article, my last for 4A Papers as the Director of 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, I am in a reflective mood. I have been a fortunate custodian of a place where curiosity is encouraged, where learning happens daily and where I’m part of a team that plays an impactful role in the development of Australian contemporary culture and its continuously evolving engagement with the wider Asian region. To have had a chance to contribute to the dynamic and driven arts of the region has been an exciting–and somewhat exhausting–aspect of the role, and one that I will miss sorely. In the weeks leading up to my departure, I began researching Valentine Willie: a figure in the art world who has long fascinated me, and who has played a pivotal role supporting curators and art historians as they delve into the art of Southeast Asia. As I depart 4A, it feels important to honour the work of someone who has actively enabled Australia’s engagement with Southeast Asian art and artists.

I don’t know when I first met Valentine, or when I first knew about him but, as anyone who has worked in Southeast Asian art knows, most roads lead back to him. Since the mid-90s Valentine has been leading small organisations, both commercial and non-profit, in Southeast Asia, and has played an undeniable role in the global ascent of art of the region. He has the kind of passion for art that becomes a life-force of its own, imbuing him with an endless energy and appetite for all things creative. This essay captures a conversation that took place in spits and spurts, via Zoom in October 2020.

Valentine Willie’s origin story is well known. He was born “upriver” in Sandakan, a township on the eastern coast of Sabah, Malaysia, about eight hours from the west coast capital of Kota Kinabalu. His father was, as Valentine terms it, “a timber man.” (1)

At the tender age of 14, Valentine was sent to the United Kingdom where, in Bristol, he attended an all-boys boarding school from the late 1960s. It was his first time out of Borneo, and he arrived in a freezing January that he describes as “cold as hell”—a counterpoint to the humid tropics of his childhood. But the culture shock was momentary: he soon adopted a British lilt, became a rugby player, and excelled academically. After completing his A Levels, he moved to London and embarked on a law degree at University College London in the early 1970s. Living in a tiny bedsit, he soon discovered that he could work and study from galleries and museums throughout the city for free. Reminiscing, he recalls “paying 10 or 20 pence an hour for the heater.” As he looked for free public spaces to work, as a result he “did all of the museums and galleries.” Valentine’s favourite was the heated sanctuary of the National Gallery where, most weekends, he swatted under the watchful eyes of Vermeer, Caravaggio and van Eyck masterpieces, developing a love and passion for visual art. It was a West Indian security guard at the National Gallery that became his unofficial art history tutor. Valentine remembers him fondly saying, “young man, you should try moving to the 16th-century or 17th-century Dutch Masters rooms, don’t just sit in this room.” And so, as he completed his degree, received his Masters, and sat the Bar exams, he moved from room to room within the National Gallery, discovering European art and developing a fascination with art history. By the time he returned to Malaysia in 1978, he was a certified lawyer and a bona fide art tragic.

With a specialty in family law, Valentine settled back in Kota Kinabalu, establishing himself as a banking and corporate lawyer. He decided on these avenues of law because, “of course, nobody got a divorce in Borneo.” While leading his own practice, he also nurtured a growing interest in the art and culture of Sabah. Having bought his first artwork in London, (“not a serious artwork, a watercolour I picked up for 1 Pound in Hyde Park one Sunday”), a weekend flutter quickly became a serious pastime. In Borneo, sourcing artworks became more than simply a means to build a collection; instead, it enabled him to reconnect with the country he had left as a young boy. In those first few years in Kota Kinabalu, Valentine was struck by the unfamiliar surroundings of his homeland and local region. Having spent the majority of his adult life overseas, he came back not knowing very much about the region or its history: “I knew much more about English history and Kings and Queens of England than I did of the history of Southeast Asia or Malaysia.” But he wanted to learn and, as he recounts with glee, “and what’s the easiest way to learn? By collecting art and looking at artists practice as an introduction to the region.” And so collect he did.

A selection of Valentine Willie’s collection of betenun work. Image courtesy Valentine Willie.

Some of the early works that he collected were textiles and, in particular, the work of First Nations artists and craftspeople of Borneo. Valentine himself is part Dayak, the people indigenous to Borneo, and identifies as a descendent of the Iban people or the sea Dayaks. The Iban women are prolific weavers, and their woven creations—(known as betenun —are both practical and cultural in importance. Valentine says, “Thirty years ago, I started collecting mats, and baskets, and textiles from Borneo.” He actively collected to such an extent that, while being a lawyer, he also had a small concession in a local department store where he sold “his extras.” With dealers and connections in Sarawak and across Indonesia, Valentine recounts tales of “people turning up at my office with all sorts of things—people would turn up with jars, baskets, fruit and fish and it appealed to my inquisitive nature.” He continues, “Some of these jars were 16th or 17th-century Chinese and in perfect condition. But how did they get to Borneo? This was the kind thing that fascinated me.” For Valentine, this deep connection with culture has no bounds; it is not directed towards a single period, medium or art movement but instead underpinned by a wholesome wonder at how cultural objects speak through time and space. As he increasingly began working with clients throughout Southeast Asia, this wonder soon focused on contemporary culture. He put aside his ongoing love of historical material culture while plunging himself into the all-encompassing world of contemporary visual art. In an era where air travel was expensive, Valentine’s work in the law demanded he travel extensively within Southeast Asia and this enabled Valentine to develop a kind of regional understanding of contemporary culture that was afforded to very few.

A selection of Valentine Willie’s collection of betenun work. Image courtesy Valentine Willie.

A selection of Valentine Willie’s collection of betenun work. Image courtesy Valentine Willie.

In each of these trips, Valentine immersed himself in the cities he found himself in, ducking down laneways to artists’ studios, wandering museums and attending exhibitions. Throughout this time, he continued to build a collection that documented his travels and increasingly expanding interests. A voracious reader (at numerous times during our Zoom call, Valentine ducked out of the frame to locate a book to show me), Valentine schooled himself in the distinct contemporary art of each of the locales he visited—whether it was Manila, Bangkok or Jakarta—delving into the nuances of Southeast Asian art. It was in the mid-80s, that he began collecting contemporary visual art in earnest and, “hasn’t stopped since.” Since then his collection has grown but has remained tightly focused on Southeast Asia. As Valentine quips, “with over 650 million people in 11 countries; it is ‘a big backyard.’”

Through this supported travel, Valentine built an understanding of the region’s contemporary visual arts landscape that was at once connected but simultaneously divergent. This perspective was rare as, until the advent of budget tourism—and in particular AirAsia’s launch of key local routes in 2006—air travel in Southeast Asia was not only expensive, but limited. Flight paths were largely between capital cities, making international access to secondary cities and beyond difficult and costly. Thus, while neighbouring countries were geographically close, they were often culturally unfamiliar and unacquainted with each other. Throughout his travels Valentine became acutely aware of the disparate nature of a region that was so intrinsically intertwined but, in reality, operating in parallel.

By the mid-90s, Valentine was well known as a great champion of Southeast Asian art and an in-depth collector. By the end of his years as a lawyer he was already being invited by the likes of Galeri Petronas in Kuala Lumpur to curate exhibitions informed by his travels and research. This experience fuelled Valentine’s need to foster a dialogue within the region that enabled fluid understandings of culture to occur. In 1996, he moved from Kota Kinabalu to the capital of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, to establish his eponymous gallery Valentine Willie Fine Art.

Installation views of Wong Hoy Cheong’s solo Of Migrants and Rubber trees held at Valentine Willie Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, 1996. Image courtesy Valentine Willie.

Kuala Lumpur was far from a contemporary art hot spot at this time, but it was a growing global gateway city that was increasingly connected to the region. Together with his co-founder Mee-Seen Loong, Valentine Willie Fine Art began presenting a program of contemporary exhibitions that enhanced the visibility of artists from Southeast Asia. Early exhibitions of Wong Hoy Cheong, Yee I-Lann and Melati Suryodarmo enabled these artists to create and present significant works that Valentine and Loong connected to audiences and curators, not only in Kuala Lumpur but throughout the region and beyond. With a growing stable of respected and talented artists, an exhibition program that sought to elucidate the contemporary realities and Valentine’s unbridled enthusiasm for Southeast Asian contemporary art, the gallery soon became a global touchstone for Southeast Asian art, a role that Valentine did not take lightly.

Valentine is a community builder: his open and sunny personality, unrivalled hospitality and infectious love of art has enabled him to bring the global art world to Southeast Asia. The early years were “not that lucrative,” as private collectors were few and far between in Kuala Lumpur. However, institutions quickly identified him as a wealth of knowledge and artistic connections. One of Valentine’s first customers was the Asia Pacific Triennial (APT), which, along with Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale and the Singapore Art Museum, lent on his nous and networks to develop their collections. He secured Thai paintings for the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale, placed Filipino works with Singapore Art Museum, and a few paintings from his first exhibition of Malaysian painter Wong Hoy Cheung were included by the Queensland Art Gallery for the second edition of the APT. As he recounts these early successes, he amusingly but modestly put them down to having “a kind of memorable name, so people remember that guy with the strange name from Borneo. It helped.”

Numerous international curators have passed through the region, with Valentine guiding them through studio visits, history lessons and giving them the lay of the contemporary art land for the day or so that they parachuted into town. He marvelled at how many of these curators “turned up” and, in particular, an uber-famous one managed to write “so authoritatively” about art from the region after visiting for only three days. “Quite astounding, how do you spend three days and write authoritatively about anything?” I asked Valentine if he ever felt that imparting all of his knowledge and time, most often for free, was sometimes a thankless task and he responded, “I was sometimes resentful of that.” Recently, two decades later, Valentine ran into this curator and, after re-introducing himself, the curator replied, “of course I remember you, how do you forget a name like Valentine Willie.” Even through Zoom, I could feel the ongoing exasperation behind Valentine’s shake of the head.

By 2000 Valentine’s reputation as a leading expert of Southeast Asian art was cemented and, despite having been dealing throughout the region since the inception of his Kuala Lumpur gallery, he formalised it by expanding his gallery to Bali. By the late 2000s, Valentine Willie Fine Art had a presence in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and the Philippines. It was fast growth that reflected the extraordinary ascent of art from Southeast Asia on the global stage. But for Valentine it was not about market share, instead it was a consideration of the audience.

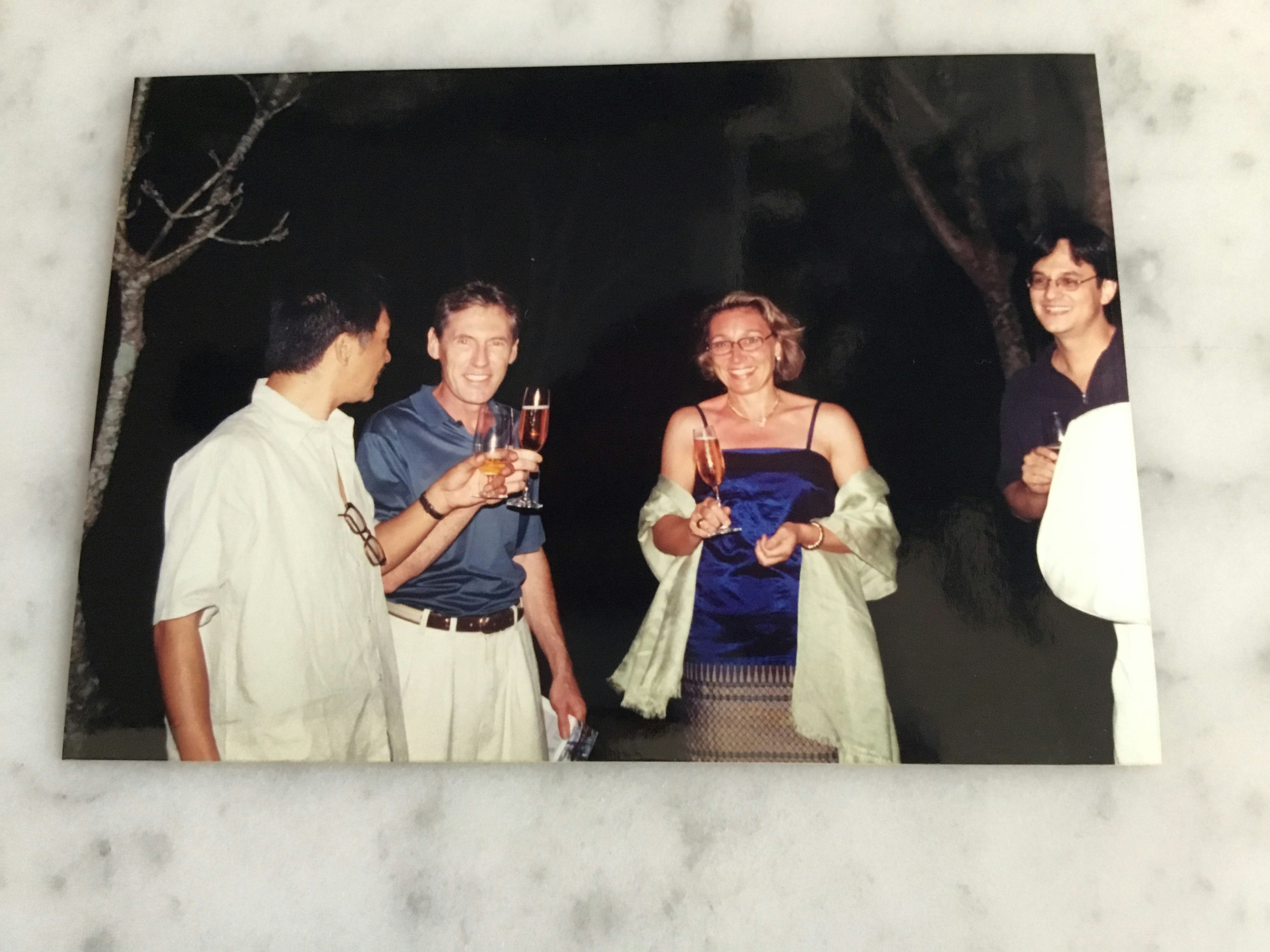

Opening of Valentine Willie Fine Art in Ubud, Bali. circa 2000 Amongst foreign guests are Australians arts patrons Luca and Anita Belgiorno-Netis. Image courtesy Valentine Willie.

While Valentine Willie Fine Art was a commercial gallery, it really operated as so much more. Embedded in a city with a contemporary commercial art scene in its infancy, the gallery played an expansive role in not only Kuala Lumpur but the region itself. Underpinning Valentine’s career in the arts is a fundamental need to develop closer cultural networks within Southeast Asia and share the work of artists within the region. Cultivating this regional connectivity was the basis for the establishment of galleries throughout Southeast Asia. Through the gallery in Kuala Lumpur he observed that for local audiences it was art from the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand that “was much more enriching” than simply art from Malaysia. When he travelled to Yogyakarta or Manila he realised people had limited knowledge of art beyond their immediate locale and he sought, through his galleries, to culturally “build bridges across Southeast Asia.” Reflecting on this action he felt that for the first decade he was building this bridge “from one side” and bringing art from across Southeast Asia back to Kuala Lumpur but, when he began his network of galleries. This became a more democratic action of building a series of bridges that traversed the region enabling contemporary culture to move more freely and “much faster”.

His network of galleries accompanied the advent of budget air travel, which also connected cultural cities internationally. Speaking of Indonesia, Valentine remembers “the best art came not from Jakarta, but from Bandung and Yoygakarta, so getting there was very difficult in the early days but; with budget travel it became much easier and cheaper.” As he travelled, he felt that, to an extent, he had the “field to himself,” pioneering a commercial market and developing access points for Southeast Asian art that enabled its art and artists to become regionally and internationally visible. With a passion for linguistics, “especially slang,” Valentine embedded himself within the art communities of the region and is now as much at home debating with a Filipino art historian as he is with an influential Singaporean collector and an emerging artist in Chiang Mai.

As this network of galleries grew and as the artistic communities of Southeast Asia continued to develop and play a growing role within international art, Valentine Willie Fine Art became an organisation run by an impressive team of staff. For Valentine “seeing where they all are now…it is my proudest work.” Impressively, aside from the gallery’s co-founder Mee-Seen Loong (a long-time Sotheby’s Chinese art expert and current Director of Ink Studio, Beijing.) and the gallery’s first curator Beverly Yong (who was trained in art history Cambridge and SOAS), most of the staff members did not have a prior art background.

The second and third wave of staff included the likes of current Director of Art Basel Hong Kong Adeline Ooi, who looked after the Philippines and Indonesia for the gallery, and Simon Soon (who was 4A’s Community Projects Officer from 2011-2012, and is now a Senior Lecturer at the University of Malaysia). Valentine’s mentorship has had a huge impact on the current generation of arts leaders in Southeast Asia, many of whom are continuing to develop a critical discourse of debate for Southeast Asian art to ensure that it holds a prominent place in global art histories.

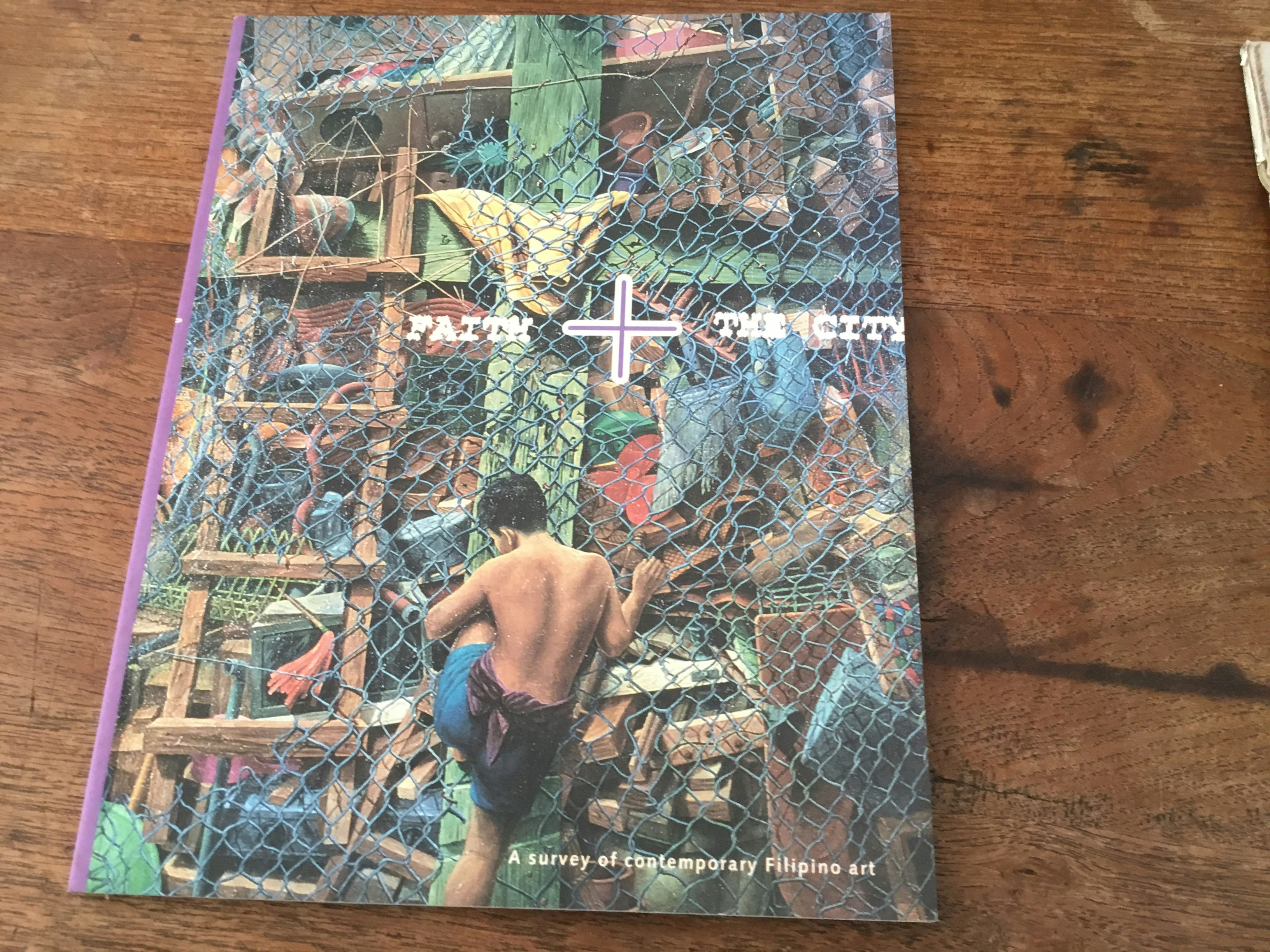

The concepts of discourse, debate and a Southeast Asian art history have been close to Valentine’s heart from the beginning of his career as a gallerist. From the outset, the gallery produced twelve exhibitions a year, with six programmed for clear commercial purposes and a further six exploratory and experimental in nature. Valentine says, “we knew we would lose money but it was a necessary part of what we did.” For Valentine, it was of critical importance that his endeavours were more than simply a commercial exercise; that they contributed to creating and supporting the growth of contemporary culture. This is evidenced by a program that featured exhibitions such as Faith + the City, a 2000-2002 travelling exhibition organised by Valentine Willie Fine Art that was “the first exhibition of contemporary Filipino art outside of the Philippines.” The exhibition began at Lasalle-SIA College for the Arts in Singapore before travelling to the National Art Gallery of Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur, ABN AMRO House in Georgetown, and The Arts Center at Chualongkorn University in Bangkok, before returning to the Philippines to the Metropolitan Museum of Manila. It featured the work of around 70 artists whose work Valentine, quite proudly, remembers “fit into one container!” Faith + the City was an undertaking far beyond the remit of a commercial gallery, but demonstrates the collaborative nature of Valentine Willie Fine Art and its overarching endeavour to create regional cultural understandings in Southeast Asia.

Exhibition catalogue of Valentine Willie Fine Art travelling exhibition of contemporary Filipino art, Faith + the City, 2000-2002. Image courtesy Valentine Willie.

After nearing 20 years running the gallery, Valentine thought it was time to close and embark on his “retirement dream” of running a museum of contemporary art that was free and accessible in Malaysia. After almost two decades, Valentine “still really didn’t enjoy” selling and was developing a growing resentment for collectors who, unlike himself, did not collect from the heart: “I resented selling to them and wished I could have kept them all instead of having to sell to some of these collectors.” His retirement gift to himself was to withdraw from the commercial art world and commit himself to supporting his beloved Southeast Asian art through an institutional position. He quickly determined that he did not want to work for any of the existing organisations and decided, as his retirement-slow-down-project “to start my own.” The idea was to create a space that eventually, in the fullness of time, would house his own collection. He first scoped a site in Penang, an island off the Western coast of Malaysia that has a long and dynamic history of culture, collectors and art lovers. An idyllic place, it has long been, as Valentine terms it, “a playground for the rich” and is dotted with “holiday mansions,” but also for many early artists and art dealers it was a great place of trade. Some of Malaysia’s earliest art galleries were located in Penang so, for Valentine, the construction of a major institution made sense. It also continued his interest in “secondary cities” and supporting the cultural growth beyond the capitals. Valentine located and secured a parcel of land in Penang’s capital of Georgetown, but a new rejuvenation plan for the city saw the local government reclaim the site and, with no suitable spaces available, the project never took off. But, in the meantime, an investor in the project offered Valentine a space back in Kuala Lumpur.

Ilham Gallery has now been in operation for more than five years. With two floors of almost 11,000 square feet, Valentine’s dream for a collecting institution was re-envisaged as a kunsthalle, a contemporary art space that hosts a rotating schedule of temporary exhibitions. His initial conditions remained: “it must be free, it must be curatorially independent: we don’t take money from the government, we don’t sell art and we don’t just do Malaysian art”. Essentially the gallery is an extension of Valentine’s work at his commercial space, continuing to deliver key exhibitions that further understandings of Southeast Asian art with at least 30% percent of annual exhibitions engaging with regional and international art movements. However, the key difference is that through IIham Gallery Valentine is able to support the development of a more formal discourse of contemporary art in the region. “I see Ilham as writing our art history as there is so little writing … another condition when I started the gallery was that every show must be accompanied by a catalogue. So at least we have a starting point and we build up some literature that can become the starting point for future art historians. The catalogues are priced to sell and just to cover costs rather than make money. It is really an important part of Ilham.”

Ilham Gallery often works with other institutions in the region, as well as with independent curators, to create exhibitions that “resonate with local audiences”. Ilham collaborated with Hong Kong-based independent art space Para Site to present the touring exhibition Afterwork, which examined how class, race and labour have informed migration in the region – the partnership enabling the production of a catalogue to document the exhibition. Another collaboration, with MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum in Chiang Mai, enabled the exhibition Patani Semasa: an exhibition on contemporary art from the Golden Peninsula to travel to Kuala Lumpur. The exhibition looked at the southern region of Thailand, just across the border from Malaysia, and explored how the Malay ethnicity and Islamic faith has impacted the region’s culture. Reflecting on why he felt compelled to support this exhibition travelling to Kuala Lumpur, Valentine remarked, “that’s just north of the border of Malaysia and we know zero about what’s going on there and the violent history they went through.” The exhibition was also accompanied by a catalogue supported by Ilham Gallery that has enabled this conversation to continue beyond the exhibition. The gallery is the means by which Valentine shares his ongoing learnings about culture from the region with audiences in Kuala Lumpur and builds an infrastructure of knowledge of art of the region.

Towards the end of our conversation, Valentine turned to the future: “I told the patrons of Ilham that I would stay for five years and nurse the institution to a firm curatorial footing with a great team and I have just passed five years, so I am considering what to do post-Ilham.” Looking towards the second phase of his so-called retirement, Valentine is returning to his first collecting passion, his textiles from Borneo and the “material culture” of the region. “We were telling stories of ourselves long before the advent of painting, sculpture and photography and written languages…it was through textiles that stories were told. The weaver was the historian of the times.” It is the woven mythologies and histories in the textiles that fascinate Valentine the most and especially those that were made not for practical uses but instead as wall hangings reflecting sacred histories.

Fuelled by a disdain for the Western construct of the term ‘arts and crafts’, Valentine now sees his next challenge as an exploration of the dynamism of indigenous art forms that are, as he notes, often by “nameless artist.” He continues, “I want to locate this in Borneo, and another impetus that inspired me to return is Indonesia announcing that they are going to move their capital in the next ten or so years to Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo.” Combined with the infrastructure of the region and the fact that Kota Kinabalu is the “dead centre” of the ASEAN in terms of geography, time zone and flight path, Valentine thought “it was time to return and give back to my home. And there is no better place to do it than Kota Kinabalu.” Valentine’s gregarious nature and political nous will ensure he can locate a site for a new space and wrangle the funding to see it to fruition. For the time being, Valentine is busying himself with amassing the objects for this future museum.

Every year Valentine treats his betenun mats with coconut oil and sunlight to prevent them becoming brittle. Image courtesy Valentine Willie.

“Lockdown has been dangerous”, he declares, “I have been doing so much online buying!” Before Covid-19, Valentine had noticed a growing number of betenun returning to the secondary market. The pandemic only seemed to increase the numbers with, as Valentine determines, “many people letting go of pieces that they otherwise would be able to afford to keep.” These shifting economic times have enabled him to buy whole collections rather than singular pieces, and his runners, from Sarawak to Yogyakarta, have been busy alerting him to new opportunities. This fervent period of collecting has only added to Valentine’s convictions that the international contemporary art community needs to be much more inclusive. “We need to include many more indigenous voices in the conversation about contemporary art and we need to break down the barriers between art and craft,” he says.

In December he hopes to return to Kota Kinabalu for a few months to find the site for the new gallery and begin to “find the money” to make it happen. Having given himself five years to get the project off the ground, Valentine is buoyantly optimistic. The thought of returning to his beloved Borneo and building a space that celebrates the works that remain the core of his own personal collection is palpable even through the digital distance of zoom.

In the days after our conversation I waited impatiently for the books Valentine recommended on betenun to arrive and was busy familiarising myself with the websites he recommended. Valentine is right: there is a depth of knowledge to these woven works that is unrivalled. They are aesthetically beautiful, realised through distinct and exemplary craftsmanship and document the rich and diverse cultures of Borneo. The knowledge systems embedded in these works are wise and collaborative and, in this age of division, are a lesson to us all.

Notes

- All quotes from Valentine Willie are excerpted from Zoom interviews with the author in October 2020.

About the contributor

Mikala Tai was the director of 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney from 2015 — 2020.