The vulnerable, dangerous and radical act of wearing their heart on their sleeve: a snapshot of Hong Kong independent art spaces

Bridie Moran

Outside the endless halls of the art fairs; away from the elevator operators who ask if you know who is showing at the commercial gallery you are there to visit (a sure-fire way to keep the just-generally-interested out); in a break in conversation about the impact M+ is going to have on the city; there is, of course, another Hong Kong art world. On the top floors of repurposed apartment buildings and in self-built lofts, operating out of mechanics’ garages and workshops, exist the newest generation of Hong Kong arts spaces. In these spaces, artists and arts workers are working together like many before them to create experiments and opportunities for local communities in an ever-shifting cultural and political landscape. The ideas are big, loose, fun, kind, angry and considered, and play a key role in the future of the city.

Hong Kong has a long-established independent contemporary art scene. Much like in other colonised countries in the Asia Pacific, Australia included, the 1980s and 1990s saw a flurry of artist-run spaces established in Hong Kong, some of which have matured into fully-fledged professionalised collections, institutions, community organisations and galleries. In 1986, new media artists grouped to form a collective, with the resultant organisation being Videotage, one of Asia’s most established new media and video art bodies. Para Site was founded in 1996 by a small group of local artists and has grown become an expansive contemporary art centre with international residency and touring programs. In 1998, was similarly founded, by a group of arts workers, since establishing itself as a space for international collaboration, community art and contemporary practice. All of this is to say: artist-run initiatives are in no way new to the Hong Kong cultural landscape. What you will read here is a snapshot of just a fraction of the new and unusual spaces in the city this year. There are many types of alternative spaces and so by way of providing a frame for this text I refer to Anthony Huberman, founding director of the Artist’s Institute in New York, who identified the power of the type of art spaces that can ‘perform the vulnerable, dangerous, and radical act of wearing their heart on their sleeve,’ and consider some of these as they stand in Hong Kong in 2018 (1).

Street view, neighbouring shops and Form Society, April 2018. Photo: Bridie Moran.

Form Society

G/F, 186 Tai Nan St

Sham Shui Po

In Hong Kong, arts philanthropists aren’t necessarily treading the polished concrete floors of H Queen’s commercial galleries, or buying up big at Art Basel’s fair at the city’s harbourside Convention and Exhibition Centre. Instead, like Wong Tin Yan, they might be donning work boots to build a space from the ground up. As founder of Form Society, a multidisciplinary art, design, retail and co-working space on Tai Nan St, Sham Shui Po, Wong has self-funded the transformation of a run-down retail shop, working days and building at night to earn the money needed to staff and launch the space in mid-2017. While the organisation collaborates with many other Hong Kong arts initiatives, such as the KaCaMa Design Lab, this independence means that the space can be responsive without having to be tied to government funding.

As is ever the case, the arrival of artists, art spaces and hipster co-working coffee shops heralds gentrification on Tai Nan St. Sham Shui Po district is situated in north-eastern Kowloon and, despite numerous urban renewal initiatives since the early 2000s, remains predominantly working class, with migrants, families and seniors living in often cramped flats and public housing estates that frame the popular street markets the area. While the arrival of hipsters normally signals the death of local small business and character, in Sham Shui Po the arrival of Form Society and other creative spaces spaces—such as co-working space and cafe Common Room & Co. and coffee shop Sausalito— has extended the retail viability of neighbouring businesses. Surrounding Form Society at street level are shopkeepers, often specialising in repairs, fabrics and leathers. Founder Wong Tin Yan says that when Form Society first opened these shops would often be closed on Sunday. However, as Form Society and its neighbouring creative spaces brought more visitors from across the city and the world to the area on weekends, Wong noticed that the shops across the way had begun to open on Sundays too.

A well-regarded sculptor himself, Wong’s model is intentionally outward looking: he customised the space to have an open front window (much like a canteen), so that passers-by could talk to and see people inside without having to enter. Like its neighbouring shops, Form Society has a retail aspect, with a display space selling artists’ books, zines, and monographs from Hong Kong and beyond. Form Society also regularly transforms itself, becoming a different space as projects change. In past months, its shop space has turned into a pop-up record stores, a ‘floating bookstore’, exhibition gallery, space for literary readings, and more. From time to time, the space is activated with events, from drop-in sessions to speak with a resident poet to, providing space for development of a local film production, Dragon’s Delusion.

For Wong, the space has become an experiment in connection with the local community, an experiment which has prompted him to consider the need for cultural spaces in the area. He writes in his reflection of one year in the space:

As the old saying goes, ‘Clothing, food, and then knowing the honour and disgrace’ means that when you are full and warm you can talk about etiquette, distinguishing honour and shame. Similarly, when basic life problems are not solved, what culture and art are you talking about? Or does the grassroots class dislike or need culture and art?

Moreover, Wong is aware of the role that his experiment may play in the future of creative spaces in Hong Kong, in light of the Umbrella Movement of 2014 and the rapidly evolving political landscape:

If you do not continue to practice all kinds of possibilities in our city, will there be any opportunities in the future? (2)

Founder Him Lo outside the Chingchun Warehouse, April 2018. Photo: Sampson Wong.

ChunChing Warehouse

6 Fung Yi St

To Kwa Wan

‘Potato Bay’ is a literal translation of To Kwa Wan, a bay area adjacent to the former Kai Tak Runway that served Hong Kong’s international airport until 1998, is home to a diverse mix of locals alongside refugees and migrants from mainland China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Turkey, and more. The area has many auto repair workshops, and (of course, arguably) some of the city’s best Cha Chaan Teng (local diners). The suburb, and those adjacent, are also known as the areas of the ‘sunset industries’ and are the among the last slated for redevelopment as part of Hong Kong’s major urban revitalisation. Currently, To Kwa Wan is one of few remaining areas of the city inaccessible by the MTR underground train line and this literal separation from the metropolitan areas of the city has let diversity and culture on this bay flourish and face challenges. In these streets, the (relatively) famed Cattle Depot Artist Village thrives, an expansive former slaughterhouse (from 1908–1999) transformed in 2001 into an enclosed community of galleries (Videotage, 1a space, and others); artist studios (until recently, the Frog King could be found here near-daily in a space now transforming into a kind of Frog-King-archive); workshop spaces; community theatre venues and more. The Cattle Depot is managed by Hong Kong’s Government Property Agency and, as the area moves ever-closer to ‘revitalisation’, the Development Bureau has appointed the Hong Kong Arts Development Council to carry out a study concerning the future of the Cattle Depot (3).

With the future of the Cattle Depot in uncertain hands (a familiar story to any arts not-for-profit living on ‘generously’ gifted government space), To Kwa Wan is also home to a small band of artist and arts worker-run initiatives that are quite literally going in to the streets to engage the local community. Surrounded by workshops, convenience stores and diners, Chingchun Warehouse doesn’t look like a typical arts space. Housed in a small workshop space behind a garage-style door, when open, the Warehouse spills out onto the street, with custom-made wooden seating and bright yellow signage inviting people inside. Founded two years ago, the Warehouse is independent: funded and made possible predominantly through a cooperative volunteer model that sees artists, arts workers and locals share access to the space. Founder Him Lo describes the Chingchun Warehouse as an ‘experiment’. With a background as a multidisciplinary artist and curator, known for his innovative and community-engaged work at Wan Chai’s Hong Kong House of Stories, and his many cooperative arts initiatives (the Wan Chai Kaifang Winery, and The People’s Pitch, a collaborative football project just some great examples) throughout the city, Him Lo speaks of being committed to activating creative possibilities to change living conditions and create connection. He explains that the initial experiment was the space’s operation as a hands-on woodworking workshop, with a master woodworker teaching a small group basic carpentry skills. Now, with the master woodworker retired at the end of 2017, the space is in another phase of experimentation, he says, to see if it can be a ‘true’ community arts space.

Interior, Chingchun Warehouse, April 2018. Photo: Bridie Moran.

Unlike other community and contemporary art spaces in Hong Kong, Chingchun Warehouse doesn’t present exhibitions. Instead, it focuses on community events, gatherings and workshops that engage people creatively in making and discussion. The Warehouse has a strong cohort of local artists and arts workers who help contribute to running the space day-to-day, selling their wares and sharing their skills: a local fashion designer sells his up-cycled clothes and accessories on the wall of the space and regularly drops by to say hello to whoever may be around; regular workshop sessions are attended by young people who learn sewing skills and access the Workshop’s sewing machine and materials; local filmmakers host screenings and discussion events that attract a wide cross-section of the community, from teachers, to designers, to cable engineers; people come together to cook and share recipes with locals contributing ingredients and ideas from down the road. In these ways, the space transforms into a site of political activation with information-sharing sessions on the future of nearby Lantau Island (another part of Hong Kong’s controversial redevelopment planning), and tables given over to banner-painting for protests. The Warehouse’s open space often attracts the interest of local workers and residents, who pop in to say hello, or ask about an event that is happening. More likely than not, they are offered tea, beer or an egg tart just fetched from the nearby bakery. While local residents are yet to play a key role in developing the Warehouse’s activities, Lo says that the positive reaction of the community so far is promising, laughing as he confesses, ‘At least, they don’t hate us!’

Foo Tak Building Elevator, April 2018. Photo: Bridie Moran.

Foo Tak Building

365-367 Hennessy Rd

Wan Chai

While it may look on the outside just like any other Hong Kong apartment building, when you step inside the Foo Tak building on Hennessy Road in Wan Chai you are met with a lobby that show clear signs of creative life with posters for art exhibitions, music performances and talks hung above a stack of arts publications outside the elevator. Inside the elevator, a number of floors are highlighted with organisation and artist names with stickers decorating the inside. The Foo Tak building was, up until 2003, a regular Hong Kong building. But when the land lady heard about how difficult it was for artists to find affordable spaces for studios in the city she turned over the twenty apartments she owned in the building to become studio spaces. While it may not be open to the public generally, it’s not new, or experimental, in the context of the city, the space is well-known among emerging artists, independent musicians and academics. Yet the generosity of this space and its vital independence has supported a great many creative experiments in the city.

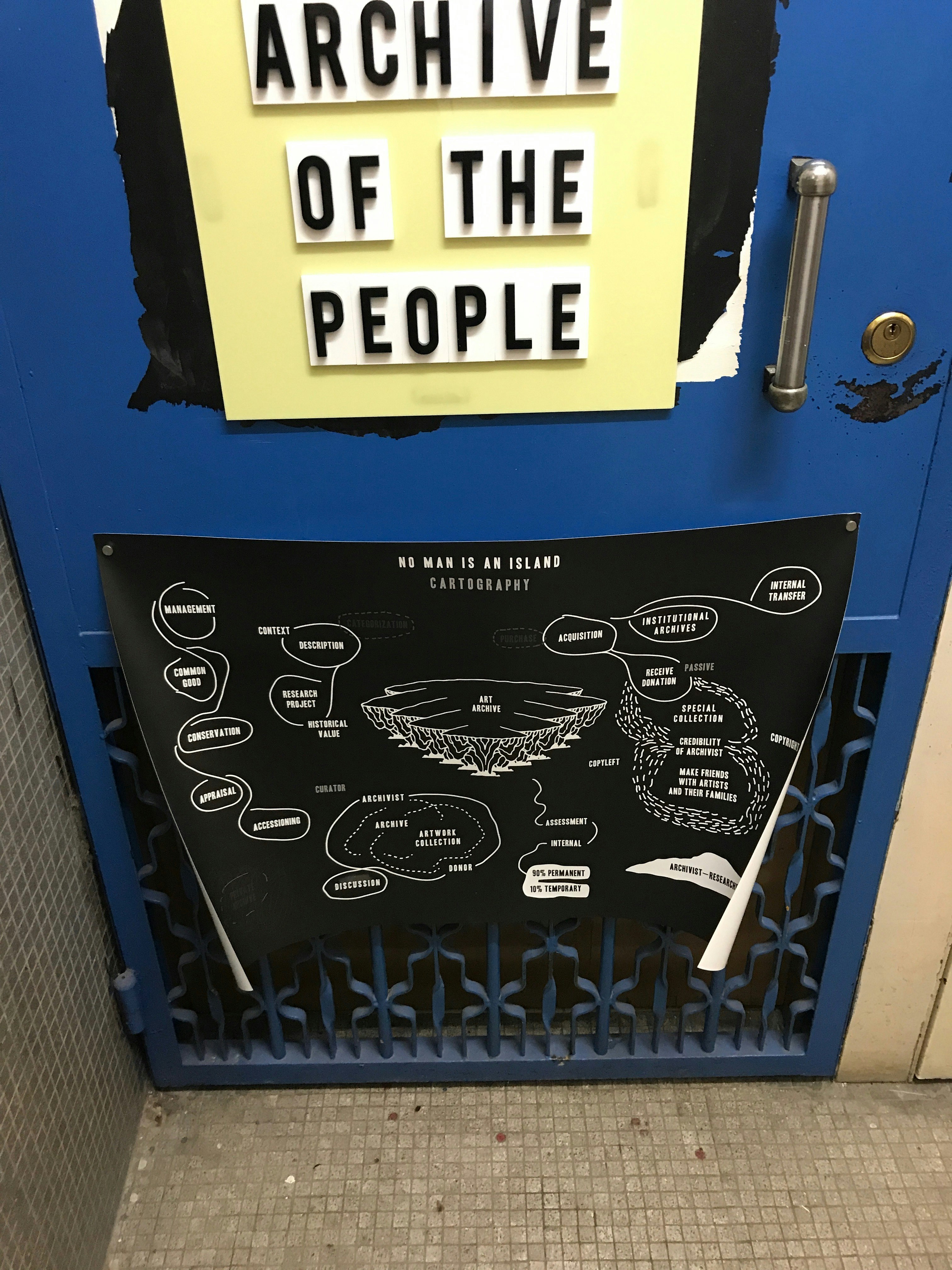

Archive of the People Front Door, Foo Tak Building, April 2018. Photo: Bridie Moran.

Artists’ studio rentals in the Foo Tak building are managed by Arts and Culture Outreach, or ACO as the locals call the organisation, that collects rent, runs programs and houses the speciality arts and literature bookstore upstairs. For many organisations in the building today, the space and piecemeal rent (HKD$4,000 or less a month, equivalent to a little over AUD$700) enables them to make work and do projects they wouldn’t otherwise be able to. As Archive of the People director, Lee Kai Chung, described it to me, ‘a place like this doesn’t exist elsewhere in Hong Kong. It’s very unusual.’ After Lee finished at university he struggled to find a space to research and store archival materials; without the space afforded by the generosity of the land lady, Lee says that the Archive of the People project would still be operating from his home. Generally, most organisations and artists are granted a two-year lease in the building, after which most are sufficient enough to support moving to an alternative space.

Rooftop Institute

Founded by three artists who met at university, with the guidance of their professor and mentor, Rooftop Institute is a resident organisation of the Foo Tak building that focuses on a mission to ‘to develop a series of imaginings and practices enacted towards the concepts of space, community, learning and exchange’ (4). For the past three years, with support from ACO and government grants, Rooftop Institute has been running an experimental education program, operating outside school and university systems. Asia Seed is a program that was established by the Institute so that young people aged 14 to 18 from Hong Kong could engage with artists, participate in design and research workshops, and travel to a city in the Asia region to understand arts practice at work in different cultures. It’s a sort of dream high school arts program meets a contemporary art museum workshop distinguished by its dedication to accessibility. Asia Seed attracts diverse applicants and the Rooftop Institute team works to ensure that participants range from students from the selective Creative Secondary School to young people from migrant and lower socioeconomic backgrounds who may have had little exposure to art galleries, artists and practice. The project ran its fourth and final cycle this year, with selected participants working with Hong Kong artist Wong Tin-yan of Form Society and Taiwanese artist Zhang Xu-zhan.

Asia Seed is overseen by Rooftop Institute founders and staff for each cycle and over the course of the program participants learn new skills in a hands-on way. For the students, says founder Law Yuk-mui, Asia Seed fills what the Rooftop Institute identified as a clear gap in arts education in Hong Kong. ‘In high school, you learn about Monet, Degas … and then these young people find themselves at university trying to understand contemporary art, concepts and theory and local art,’ he expressed to me. By connecting young aspiring arts professionals with practicing artists, Asia Seed attempts to fill in some of those gaps for students as they go on to higher education and arts jobs. Strengthening this strategic aim, Rooftop Institute run a number of additional programs across the year, developing artist-in-residence programs, research and more. The three founders each have their own artistic practice but spend one day a week together at Foo Tak (where they have been a resident organisation for the last two years), meeting and working together on Rooftop projects. While the Institute shares its work though talks, screenings, exhibitions and workshops, its home in the Foo Tak building is appointment-only and also used by the founders as their studios.

There’s lots more:

Blue House Studio

CCCD Artspace

碧波押 Green Wave Art

Oil Street

Space 27

Fixing Hong Kong

… the list goes on and has inevitably been updated as you read this

Fuelled by passion, long days at work followed by sweaty nights building things, beer, chats, generosity and experimentation, Hong Kong’s artist-led programs and spaces keep breaking new ground and play a vital role in securing independent creative conversations for the city’s residents. As artist, activist and key player in the city’s community arts network Sampson Wong said recently, the impact of these spaces is manifold:

Strengthening civil society is important. The Umbrella Movement used up 10 years’ worth of energy from Hongkongers … and maybe these community spaces are in a way rebuilding that capacity.

As Hong Kong becomes ever more linked, both internally and externally, it is these art spaces—essential experiments of wearing one’s heart on an organisation’s sleeve —and their successes and successors that will provide a blueprint for what can be possible in the city.

Notes

A thanks

My insight into these spaces wouldn’t have been possible without the hugely generous mentorship of Candy Sum, arts PR expert extraordinaire, community arts volunteer and avid supporter of the city’s creative fabric. Big thanks to Candy, Sampson Wong, Him Lo, Wong Tin Yan, Law Yuk-mui, Lee Kai Chung, and all the artists, volunteers and community members who spent time with me and fed me amazing snacks and ideas as I researched in Hong Kong over April 2018.

Notes

(1) Anthony Huberman, ‘Take care’ in Circular facts, ed. Mai Abu ElDahab, Binna Choi and Emily Pethick (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2011). Available online here.

(2) As quoted by International Association of Art Critics Hong Kong [accessed 1 November 2018].

(3) Kowloon City District Council Development Bureau [九龍城區議會發展局], ‘Report on Heritage Conservation; Revitalisation of Stone Hut and Ex-Ma Tau Kok Animal Quarantine Depot together with Conservation of Lung Juen Stone Bridge’ 文物保育工作匯報與石室、前馬頭角牲畜檢疫站活化項目及龍津橋的保育工作”, Document No. 24/09 [九龍城區議會第24/09號], 19 March 2009 (in Chinese).

(4) ‘About Rooftop Institute‘ [accessed 1 November 2018].

About the contributor

Bridie Moran is an arts manager, editor and programmer, with extensive experience in art, craft and publishing, who has worked for over a decade with contemporary art and cultural organisations.