Wearing Adidas in Guizhou

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan rehearsing in Longli’s Wang ancestral temple; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Writing at the time of the 1997 handover, Ackbar Abbas, then chair of comparative literature at the University of Hong Kong, highlighted increasing anxieties around the disappearance of Hong Kong culture. Under British colonial rule, argued Abbas, Hong Kong adopted a ‘floating’ identity where everything was provisional, space was transient, and politics was met with apathy. Now fearing that China would impose alien values and ideologies on the city, numerous Hong Kong thinkers, writers and artists began to search for a stronger local identity. For Abbas and many others, Hong Kong and mainland Chinese are culturally and politically distinct—essentially, two peoples.

In this climate of mistrust, my parents instructed me to clarify that I was Hong Kong Chinese when we migrated to Australia a little before handover in 1996. When I relayed this information to my new classmates, most of them were confused: Aren’t you all Chinese? Isn’t Hong Kong a part of China? To be honest, I was as perplexed as they were. Besides, I was too busy working out why on earth people liked Vegemite to posit the differences between being a mainlander and a Chinese abroad.

Over the years, I developed a vexed relationship with China which I had never visited. I internalised problematic stereotypes of mainlanders in the Hong Kong press; that they were uncouth and corrupt. Yet, I often identified as simply Chinese when interacting with non-Chinese people. Recycling obvious Chinese cultural signifiers was a way to mark my difference in a predominantly white society. Anthropologist and curator Michael Herzfeld calls this ‘structural nostalgia’, where diasporic communities imbue their homelands with an Edenic aura, transforming cultural symbols from their pasts to make sense of their newfound foreignness.

The rapid embrace of capitalism in modern China, however, meant that cultural relics were shifting or disappearing. In my art practice I started to explore ideas around original and fake, racial essentialism, and the circulation of myths in the global knowledge economy. As Asian studies scholar Laikwan Pang points out, the West is simultaneously frightened and fascinated by China’s seeming ability to conjure up anything in the capitalist market. Regulations are poor and official government discourse contradicts reality. From the popularity of shānzhài (山寨), or counterfeit culture, to egregious safety hazards such as the 2008 milk powder scandal, China showed all the symptoms of a post-Socialist nation in transition which deeply intrigued me.

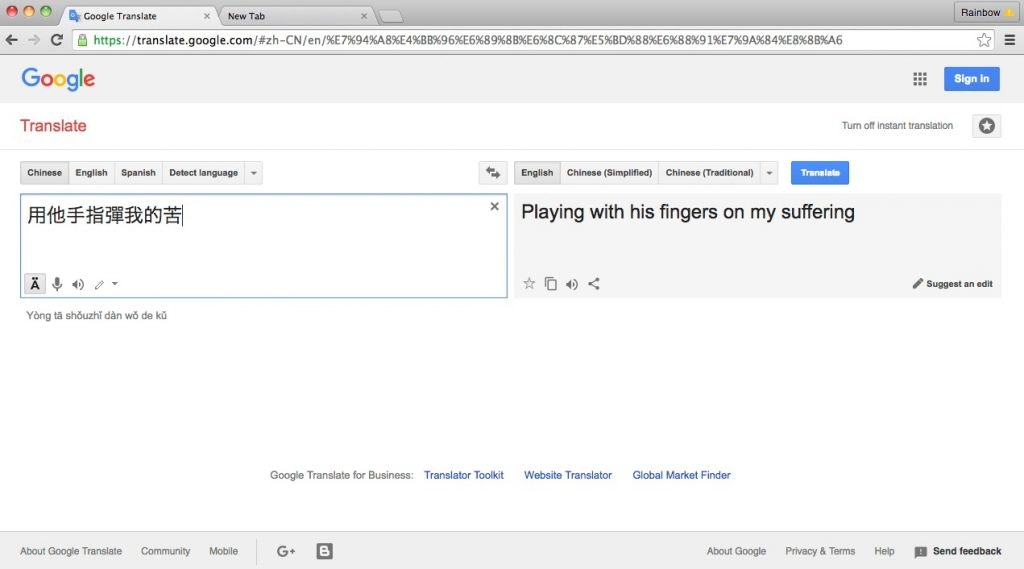

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan, Broken Vessel of 1996 (still showing Google Translate of lyrics to Killing Me Softly); courtesy the artist.

It was a crisp Monday morning when I received news from 4A that I’d been invited to participate in the First Longli International New Media Arts Festival in eponymous ancient town situated in the south-western corner of Guizhou province, China. Not only was I excited that I could contextualise my research firsthand, but I heard from my parents that Guizhou was my great-grandmother’s home province. My theoretical and spiritual desires coalesced into a warm, glowing knot in my chest. I packed all the materials required for my performance work, Broken Vessel of 1996: video, calligraphy brush, rice paper, cinnabar paste, and a marble seal bearing my name. Accompanied by the two other Australian artists I would be exhibiting with, Owen Leong and Kynan Tan, along with 4A’s Program Manager, Pedro de Almeida, we immediately bonded over neck pillows as fashion statements and mysterious ‘chicken’ on the plane that turned out to be pork. We knew this would be a memorable experience.

Guangzhou airport greeted us with its thick, humid and stormy atmosphere and, following a sumptuous dim sum breakfast in an empty dining hall that a chaperone had organised to kill both appetites and the six hours before our scheduled high-speed rail departure time, we were on our way north to Guizhou. As we travelled through a beautiful karst topography, I wondered what Longli’s festival would be like. The program remained an enigma to us as we received little information from the organisers. I had read in the press release that the festival was organised by the China Institute of Stage Design and supported by the Chinese Culture Industrial Investment Fund, among others, which sought to promote the idea of ‘environmental protection, coexistence, boundary-crossing, Longli, the world and other relevant elements.’ It also described Longli as a ‘secluded and primitive’ ecological museum with architecture and cultural practices that date back to the Ming dynasty. I pondered over the long-term benefits of this festival for the locals. How will tourism transform the town? What responsibilities do artists and organisers have to engage with the ancient village in a sustainable and meaningful way?

Driving to Liping on a mountainous freeway; photo: Chun Yin Rainbow Chan.

We arrived in Liping County (黎平县) where our hotel was located, about a forty-minute drive from Longli (隆里) which is situated to the north in the adjacent county of Jinping (锦屏县). Liping is home to mainly Miáo (苗) and Dòng (侗)people, two of the 56 ethnic minorities officially recognised by the PRC. From there we were escorted to the region’s hub in Jinping, where a large-scale outdoor concert featuring traditional arts and cultural performances had been organised in celebration of National Day, a public holiday that marks the PRC’s founding on 1 October 1949. Seemingly aimed at a select group of party faithful and invited guests while locals jostled for a view from the surrounding crowded streets, apartment blocks and construction sites, Longli’s festival participants—myself included—were given VIP treatment, seated front and centre. To get there, we walked over an old bridge on which single women and men used to court one another with song and dance, and onto a concrete island where the giant outdoor stage was erected. An impressive LED screen was flanked by towering speakers. Drones overhead captured the stage show, playing it back to the audience with theatrical cuts and edits. The concert presented Miao and Dong folk songs that had been updated with electronic beats, while its performers wore bright traditional dress. Soloists lip-synced with hyper-emotionality; dragons and lions shimmered under the blazing sun in their polyester costumes. A firework display in the shape of a colourful mushroom cloud signalled the finale, drifting and blending into an ominous grey billow above our heads.

Clockwise from top left: concert finale for celebrations of National Day, Jinping; scene from opening night of Longli Festival (photos: Pedro de Almeida); shoe purchase, Liping; dragon boys performance, Longli (photos: Chun Yin Rainbow Chan).

In Jinping’s oppressive heat, I started to feel sick and so ended up skipping that evening’s opening ceremony in Longli Ancient Town. Much to my amusement, Kynan, Owen and Pedro studiously updated me via WeChat snaps and videos of the action—spectacular to say the least. Popping and locking to dub-step were what appeared to be Chinese Star Wars stormtroopers (shānzhài!), with several drones shooting mini fireworks into the audience. There was a lip-synced performance by Russian pop star Vitas, whose Wikipedia entry enlightened us with the factoid that one of his music videos portrays him as ‘an eccentric lonely man with fish gills who lives in a bathtub with jars of fish and plays the accordion naked.’ During a folk duet between two singers hoisted above the throng in cherry picker cranes, one of the carriers caught briefly on fire. The 15-minute extravaganza was followed by a comparatively dry, hour-long speech from sponsors and government officials. All of which unfolded in front of a newly renovated páifāng (牌坊), or memorial archway gate, with a neon glow. I recently read an article that criticised the over-usage of the word ‘crazy’ to describe contemporary China, but this was coming close to it.

Longli cobblestone street in the early morning; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

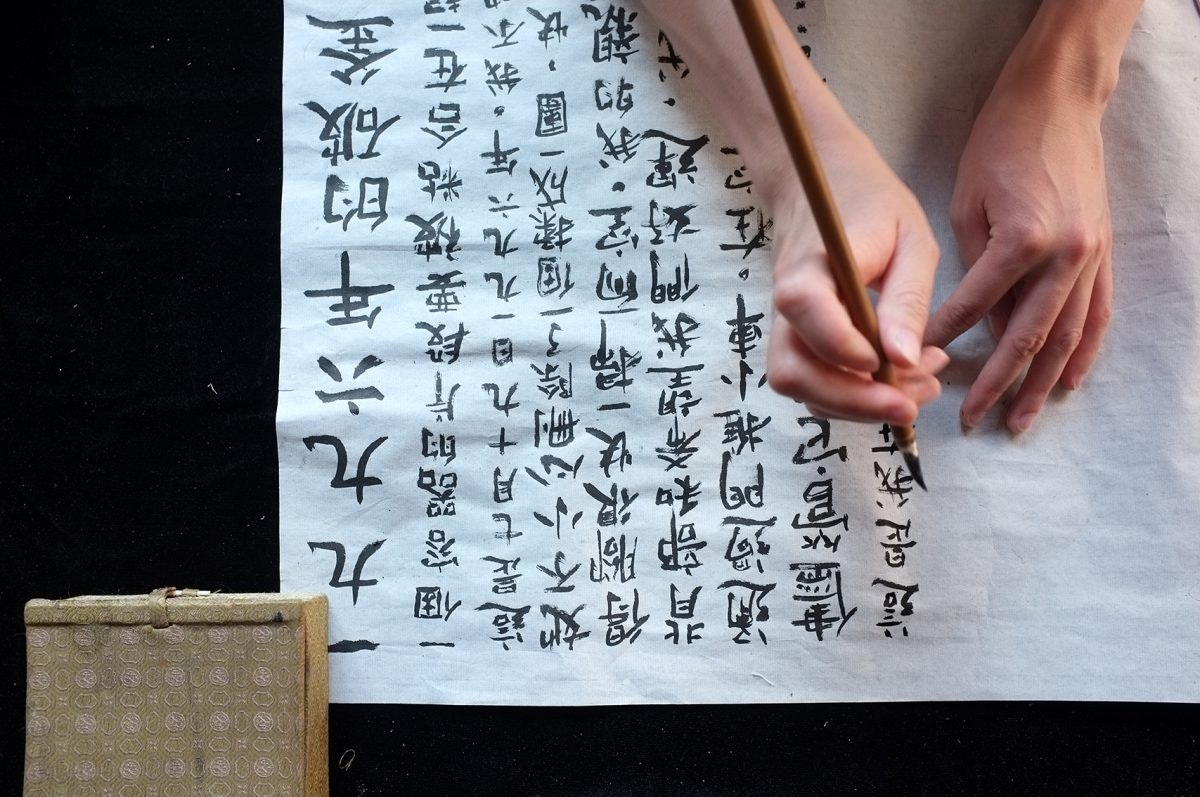

With the festival underway, Owen, Kynan and I exhibited our works in the Wang ancestral temple in the middle of Longli’s cobblestoned grid. The festival included works by notable Chinese artists such as Song Dong, Chen Qiulin and Feng Feng; art school students from several prominent institutions in south-western China such as the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute and Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts; and a handful of international artists from Korea, Singapore and Austria. Attended by local residents and Chinese travelers, the streets bustled with amazing food stores, straw hat stands and families who enjoyed round-the-clock dragon dance displays as much as the sounds of Drake and Flume being blasted over a lotus pond. I performed Broken Vessel of 1996 daily, which consisted of me singing ‘90s Western pop songs that I had translated into Cantonese via Google Translate. I also performed a calligraphy piece, using a narrative of mine which was similarly processed through the app. As a comment on assimilation, standardisation, and my personal feelings of shame in such processes, the reimagined pop songs sound humorous to a Cantonese-speaking audience as the language’s natural tones are overridden by the songs’ melodies. The garbled translations are thus rendered completely absurd.

Many Mandarin-speakers did not understand Cantonese or the traditional Chinese text in my work. I tried my best in broken Mandarin to explain the concept to interested audience members who seemed to have all different types of Chinese accents. Local toddlers sauntered in and danced along. Two roaming chickens attended every performance. Overall, I felt the performance worked, but I mused over the monolithic representation of ‘Chinese’ on Google Translate and other global platforms which erase the heterogeneity of Chinese experiences. Standardisation is, of course, convenient. It assists the flow of global capital. But I couldn’t stop thinking about the regional differences I’d witnessed. Even within Miao communities, some dialects are mutually unintelligible. What is the future of these nuanced markers of identity in our ever-globalising world?

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan performing Broken Vessel of 1996, Wang ancestral temple, Longli; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan, Broken Vessel of 1996, 2016, calligraphy performance, Wang ancestral temple, Longli; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

During the festival, we were accompanied by staff who were truly incredible and hospitable. I had an inkling though, there was perhaps an official version of Guizhou that we were meant to see. When we got wind that a small group of Chinese artists planned a secret day trip to another Dong village, we accepted their invitation. Despite being harangued on the phone by one of the organisers who was concerned for our safety, the escapade was the highlight of the trip for me. We visited the scenic Dimen Village whose residents live a traditional way of life but enjoy 4G mobile connection and one satellite TV in the community hall. Fascinatingly, I learned that a tree is planted for every child born in the village, later turned into a coffin which the owner will build for him or herself in old age. On the way back, we stopped by Mao Gong Village for lunch, enjoying exquisite Dong cuisine and drinking homemade rice wine from a repurposed gasoline tank. We shared jokes and stories in different languages, connecting us through imperfect and broken forms.

One of the art professors couldn‘t attend my performance that evening and urged me to sing around the table. I was nervous and recovering from a cold, but I mustered up the courage to sing the only Chinese song I knew, Yueliang Daibiao Wo De Xin (月亮代表我的心, The Moon Represents My Heart), the Teresa Teng classic that my mother used to always sing around the house. When I forgot some lyrics midway, a little girl in the restaurant joined in. Soon, the entire restaurant was singing and clapping along, and the video was uploaded and shared on WeChat within a matter of seconds. This was probably one of the most ‘Chinese’ moments I’ve ever felt—a connection through song, food, stories and WeChat stickers. It wasn’t official—it certainly wasn’t spectacular—but the beauty in its mundaneness and imperfections seemed to resonate with all of us.

Lunch in Mao Gong Town, Liping County; photo: Pedro de Almeida.

Throughout the trip, I was transfixed by bombastic and clichéd reenactments of Chinese culture by Chinese people. I guess this sort of historical self-narrativising happens everywhere. I mean, how often do we cringe when ‘thongs, barbies and kangas’ are used as markers of Australian identity? Claims to authenticity seemed more and more suspect to me, especially in today’s milieu where capitalism is the driving force between societies. Does it matter anymore that I’m Hong Kong Chinese and not mainland Chinese if we all end up wearing Nikes and Adidas? Belonging to a unified body has always been an active act of imagining and re-inscribing. Rituals, values and cultural signifiers have always been defined by various groups vying for dominance.

A spectacle, Guy Debord argues, is ‘a social relation among people, mediated by images.’ He continues: ‘The spectacle cannot be understood as an abuse of the world of vision, as a product of the techniques of mass dissemination of images. It is, rather, a Weltanschauung which has become actual, materially translated. It is a world vision which has become objectified.’ As I left Guizhou, deeply grateful for the experience that Longli Festival offered, I recalled a factoid. In the last three years alone, China has poured more concrete than that used by the US in the entire twentieth-century. Leaving Liping on a mini bus headed for the bullet train further south, I took a photograph of a half-constructed concrete building and meditated on how competing versions of China might continue to be materially translated. What will its world vision be for itself and the global stage? And what will the world’s vision be of it?

Construction site by the Qingshui River, Jinping, Guizhou, 1 October, National Day of the People’s Republic of China; photo: Chun Yin Rainbow Chan.

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan, Owen Leong and Kynan Tan participated in the First Longli International Arts Festival presented by China Institute of Stage Design and The People’s Government of Qiandongnan Autonomous Prefecture, Longli Ancient Town, Jinping County, Guizhou, China, 1–5 October 2016.

Notes

Abbas, Ackbar. Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Fredy Perlman. Detroit, MI: Black & Red, 1970.

Herzfeld, Michael. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State. New York and London: Routledge, 1990.

Kuehn, Julia. ‘China Abroad: Between Transnation and Translation.’ In: E. Ho and J. Kuehn, ed., Chinese Abroad: Travels, Subjects, Spaces. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006, 23–42.

Pang, Laikwan. ‘China Who Makes and Fakes: A Semiotics of the Counterfeit’. Theory, Culture & Society 25.6 (2008) 117–140.

About the contributor

Chun Yin Rainbow Chan ( b. 1990, Hong Kong, lives and works in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) is a multidisciplinary artist who works across sound, performance and installation.