Stones rot, words don’t

Mitiana Arbon

Writing and thinking these lines in English, a language imposed on my ancestors and those of you

who read this with ease, it becomes clear that to use this cultural, philosophical, economic

framework to consider the wealth of endeavours currently underway to awaken and embody

Indigenous languages is ineffectual.— Léuli Eshrāghi (1)

E pala maʻa, ʻae lē pala ʻupu (stones rot but words last forever).

— Sāmoan Proverb

I start with these two quotations as this essay’s point of departure. The first is a catalogue description for the exhibition Wansolwara: One Salt Water, the other a popular ancient Sāmoan alagāʻupu (proverb) used to speak to the importance of words and the enduring nature and richness of orality, myths, legends and history. For many Indigenous communities, the search for and articulation and engagement of their languages in all spheres of life reveals the ongoing and continuing connections to lands, spiritual connections, and aesthetic relations to the past amid colonial spectres.

Differing in fluency and competency—mine a mix of broken Sāmoan English—we tell stories of migration, dislocation and, in many cases, state-sanctioned violence. Language also offers innovation and new ways to heal political trauma through the creative plasticity of connections, reasserting presence, reshaping and decolonising art history. Such potential for creative and productive abilities to ‘embody and awaken Indigenous sensual and spoken languages’, as the wall text proclaims, is a key focus for Wansolwara, the multi-sited series of exhibitions, performances and events undertaken by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art and UNSW Galleries in Sydney, from 17 January to 18 April 2020.

From the symposium opening, audiences were reminded by Dr Léuli Eshrāghi, Curator of the exhibition O le ūa na fua mai Manuʻa, mounted at UNSW Galleries, to feel uncomfortable with the very nature of the anglophonic dominance in the gallery:

Speaking in English right now [in the gallery space] is a form of violence onto this Bidjigal and Gadigal Country that is both epistemic and spiritual, whereby the possibility of connecting and respecting this sacred territory on its own terms through the knowledges of local First Nations, through humility-based deep listening, is excluded by Western structures of linearity, discourse and control. (2)

Connecting with First Nations communities’ creative language as an act of decolonising the White cube was a core interpretative aspect of the exhibit. Throughout, language was drawn upon in contextual labels, by the artists, and shaped by the curators and writers in an effort to materialise and centre community perspectives. A term drawn directly from Solomon Aelens Pijin with equal resonance in Bislama and Tok Pisin, wansolwara, literally meaning ‘one salt water’ or ‘one ocean, one people’, is a reference to the productive possibilities of semantic interconnection through the world’s largest body of water.

This curatorial approach mobilises what Tongan Fijian writer and scholar Epeli Hau’ofa describes as possibilities in which: “Just as the sea is an open and ever flowing reality, so should our oceanic identity transcend all forms of insularity, to become one that is openly searching, inventive, and welcoming”. (3)

Eshrāghi draws upon this diverse constellation of artistic communities to map a creative trans-Indigenous dialogue that, as the exhibition wall text tells us, ‘spans the intellectual and material territories of Yirrkala to Santiago, from Sydney to Kuujjuaq.’ This ambitiously expansive approach was echoed in a solo space in Wansolwara at UNSW Galleries, Shivanjani Lal: Beta, ek story bathao, in which Lal’s video work में यहाँ नहीं हुँ (I am not here) (Fiji) (2017) physically and conceptually sought to erase boundaries of geographies to create new spaces of possibility.

Fundamental to O le ūa na fua mai Manu‘a‘s interpretative value is its subversions—not only of art’s colonial gaze, such as Angela Tiatia’s literal return of the White masculine stare in Dark/Light (2017)—but also of art’s textual colonisation through writing and contextual framings. The title of the exhibition O le ūa na fua mai Manu‘a (‘the rains came from Manu’a’) is another alagaupu, describing the incoming rain from the Sāmoan islands of Manu‘a (currently within the unincorporated territory of the United States), and is a poetic reference to the bittersweet or melancholic moments leading to much-needed change. It is also a reference to the refreshing and unprecedented collection of mixed-medium digital art activating the space with diversely spoken, written and performed aesthetic conversations.

The darkened space of the ground floor of UNSW Galleries washed audiences in sensorial waves of whispers, music, words and movements. Each of the ten artworks worked as an autonomous microcosm, drawing the viewer in to consider different ways of seeing, viewing and understanding Indigenous experiences grounded in Indigenous languages. In line with the conceptual framework of interpretative inclusivity, wall texts were inclusive of the co-habitative presence of words in Anishinaabemowin, tʔɨnɨsmuʔ tiłhinkʔtitʸu, Solomon Aelen Pijin, Mapudungun, Sāmoan, Māori, Chamorro and barrkuŋu waŋa, and were presented un-italicised in a form equal to English-language words. This written aspect was expanded as an ongoing conversation in the gallery space, as artists engaged auditory, written, visual, vocal and historical mediums in an attempt to bring into consciousness a broader understanding of heterogenous world views.

Sebastián Calfuqueo Aliste, 'Welu Kumplipe Mapuche' (installation view), 2018, UNSW Galleries, 2020. Photo: Zan Wimberley

In the first artwork encountered, Welu Kumplipe Mapuche (2018), artist Sebastián Calfuqueo Aliste brings into frame the short-lived Indigenous Law in Chile initiated by then President Salvador Allende (1970–73), recognising the distinctive culture and history of Mapuche people. The multimedia installation features a video by Aliste who stands directly in front of the camera reciting texts by art theorist Cristián Vargas Pailahueque that have been translated by the artist into Mapudungun. The speech is supported by the Mapudungun phrase ‘Welu kumplipe’, made with resin and soil from Bidjigal land, which translates as ‘he ought to fulfil what has been promised’, a conversation on continuing Mapuche rights to much larger territories still occupied by the Chilean settler colonial state.

Visual meditation on the inter-textual relationship to land is expressed by yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini artist Sarah Biscarra Dilley. Her first animated work, kʔimitipɨtyʔɨ (2019) imprints relationality between land, water, sky and kin encoded by spoken words in tʔɨnɨsmuʔ tiłhinktityu language, over layers of familial photographs and across images from tissimassu, a yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini village in southern California, and her signature chevron projected on the wall. This is a form of visual codeswitching for the artist—allowing for her own authorship over culturally authorised and colonially created archives of knowledge. Similarly, AASAMISAG (2019), a fast-paced multilingual video by Anishinaabe artist Faye Mullen narrativises Indigenous dislocation and resistance through visual layering. Presented as a screenshare of a computer, the work moves swiftly between written texts in Anishinaabemowin, English and French, overlaid by artworks, films, YouTube videos, images of border zones and quotes from thinkers: a dissection of the visual translation needed to imagine Indigenous identities across new neo-colonial textual and spatial realities.

A highlight of the exhibit was award-winning Yolŋu Gutiŋarra Yunupiŋu’s two-channel installation Gurruṯu’mi Mala—My Connections (2019). Located across ten screens, Yunupiŋu’s self-portrait speaks his embodied gurruṯu kinship system through ten signs in his first language, barrkuŋu waŋa (language from a distance), also known as Yolŋu Sign Language. Each sign indicates different clan territories through kinship names. My Connections was in close dialogue with the adjacent Bundjalung and Ngā Puhi artist Amrita Hepi’s performance-based projection of A Body of Work (At The End of the Earth) (Waangenga Blanco) and (Jahra Rager) (2017). Described as ‘argonautical visual dialogues’, both works entreat an embodied connection to places—both the mundane and spectacular gesturing—as Blanco and Rager dance across and beyond the socio-political landscapes within Australia. Alive in both works is a linguistic disruption of communications that focuses on audio- textual qualities, shifting our perception of Indigenous communication to include the unspoken and embodied understandings of place and culture.

Caroline Monnet, 'Creatura Dada' (installation view), 2016, UNSW Galleries, 2020. Photo: Zan Wimberley

While the Sāmoan proverb that stones may rot while words outlive the material might be true, in the case of Hepi and Yunupiŋu, it is equally true that our actions can express such connections just as clearly. This is perhaps a reason that Wansolwara is accompanied by a writers program that includes a number of young Pacific Islander writers: Tongan–Australian author Winnie Dunn, Cook Islander–Sāmoan–NZ European curator and writer Talia Smith, and Indigenous and Polynesian TV writer and text-based artist Enoch Mailangi, alongside myself, to discuss and respond to the exhibit. For many Indigenous peoples, in particular Pacific Islanders, to be able to write about, with and for our people can be a radically empowering act—particularly in Australia. I was reminded by Dunn that claiming a space as a writer can be equally as powerful in representation—as in their reckoning there has never been an Australian novel authored by a Tongan. This was perhaps one of the most potent parts of the exhibition; to be surrounded by other young Pacific writers, to actively claim a space within the development of knowledge in an art institution, to be able to speak candidly and for ourselves. As Winnie Dunn wrote in Meanjin, ‘for Pacific/Pasifika people to be given space to see our cultures as worthy of study, and to study them for ourselves … is an act of decolonisation.’ (4)

Developing and nourishing spaces and places that centre Indigenous interpretations and authorship are key to deconstructing and centring Indigenous ways of knowing and being. This was activated humorously by Anishinaabe and French artist Caroline Monnet’s video piece Creature Dada (2016), which deploys an interpretation of ‘Dadaism as an artistic movement led by Indigenous women working in culture’ (adjacent wall text).

Similarly, at 4A’s galleries Tāmaki Auckland-based Vaimaila Urale’s Manamea ma Anivanuanua (2020) presented a textual de-centring of western art history. Commissioned for Wansolwara, the large-scale installation consisted of a ceiling-high series of large black cards in which a set of repeated keyboard punctuations of commas, dashes, semi-colons, full stops and parentheses were featured. The complete effect of the symbols reveals a pattern found within siapo (tapa cloth), tatau (tattooing) practices, ancient Lapita pottery, and is also reminiscent of ASCII art. Manamea ma Anivanuanua brings into focus the polysemic intersectional coincidence of the digital realm of contemporary Sāmoan communities with ancient cultural practices, allowing practices to spatially coexist and converse across time. Artists that centre such culturally contingent interpretation require immense foregrounding of Indigenous Sāmoan knowledge and history, stretching from the present to epic voyages in deep time, in order to adequately reflect the totality of their aesthetic practices.

Vaimaila Urale, Manamea ma Anivanuanua, 2020, black card and sand, 240 pieces across two walls, each wall installation measuring 5940x2520mm. Photo: Kai Wasikowski for 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. Courtesy the artist.

However, as Sāmoan author and writer Lana Lopesi highlights, developing a better understanding of Pacific multilingual art practices:

requires far more resources to receive an authentic understanding of practice. We need to produce multilingual interpretations, overcome cultural barriers and educate, as well as appreciate. (5)

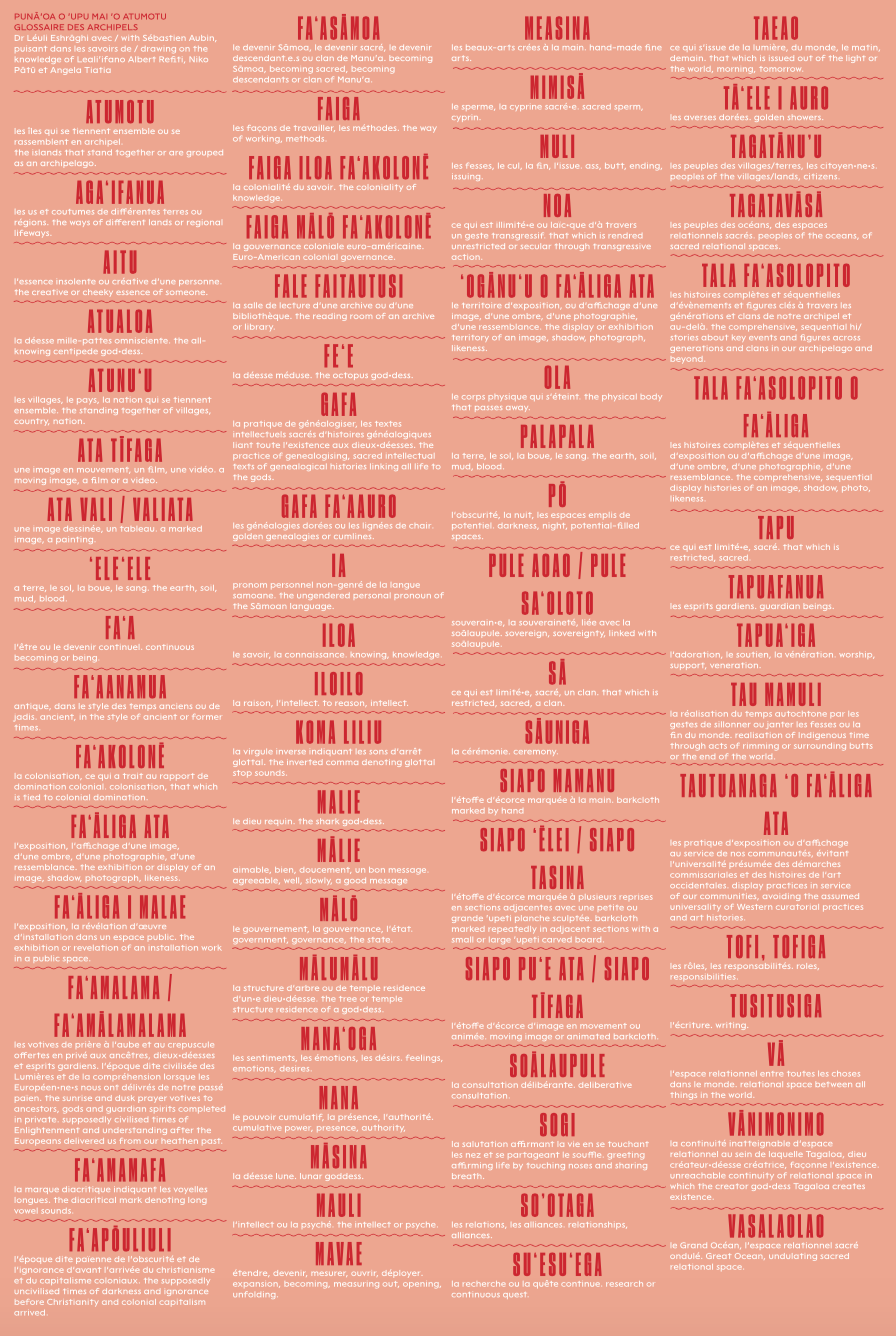

One such imagining of Lopesi’s vision could include Eshrāghi’s open source Sāmoan–French–English graphic art poster co-developed with Nēhiyāw designer and typographer Sébastien Aubin. Developed in conversation with a number of Pacific scholars during his doctoral research, Punāʻoa o ʻupu mai ʻo atumotu/Glossaire des archipel (2019) is a shareable Indigenous glossary of words, thoughts and currents in visual culture. Such approaches attempt to engage with efforts to reimagine the space in ways that centre Indigenous meanings as the point of departure.

Dr Léuli Eshraghi with Sébastien Aubin, Punāʻoa o ʻupu mai ʻo atumotu Glossaire des archipels, courtesy Dr Léuli Eshraghi, 2019.

Perhaps one of the most diverse collage of contemporary Indigenous Oceanic artists outside of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art at the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, Wansolwara has taken a step towards creating a curatorial grammar that speaks to the vibrancy of contemporary Indigenous art practices. The use of Indigenous language is key to remind ourselves that our ancestors speak through us and our embodied creative practice—helping shape the revival and renewal of our creative futures.

Through the act of writing I am reminded that stones rot, but words don’t. This highlights the importance of continuing to develop a body of writing that materialises our own critical perspectives grounded in our own histories. This is not only of importance in educating the art ‘world’ but also an intellectual act of empowerment through the decolonisation of our creative knowledge. ‘For fuck’s sake’ was the reaction that many of us had to the Sydney Morning Herald’s review (6) of Wansolwara, as ‘Captain Cook’ made another unwelcome intellectual incursion into a Pacific art discussion— despite not being mentioned. I thought we had eaten him out of the picture already.

Notes

(1) Léuli Eshrāghi, E PALA MA‘A, ‘AE LĒ PALA ‘UPU catalogue essay, UNSW Galleries, 17 Jan–18 Apr 2020, https://artdesign.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/atoms/files/catalogue_o_le_ua_na_fua_mai_manua.pdf

(2) Léuli Eshrāghi, keynote speech, Wansolwara Symposium, UNSW Galleries, Sydney, 18 January 2020.

(3) Epeli Hau’Ofa, We are the Ocean: Selected Works, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

(4) Winnie Dunn, ‘Island Life: Working the Field’, Meanjin, https://meanjin.com.au/blog/island-life-working-the-field/. 25 May 2018, Accessed 20 March 2020.

(5) Lana Lopesi, Contemporary Pacific Arts Festival Symposium Paper, delivered at the Contemporary Pacific Arts Festival Symposium, Melbourne, Australia, 2015.

(6) John McDonald, ‘New wave of Pacific contemporary art: best maybe yet to come’, Sydney Morning Herald, https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/new-wave-of-pacific-contemporary-art-best-maybe-yet-to-come-20200224-p543qo.html, 28 February, 2020.

About the contributor

Mitiana Arbon is a Sāmoan–Australian Pacific Studies doctoral candidate at the Australian National University, Canberra.