Defining Taiwanese Identity: Constructing Narratives Through the Institution and Within Artistic Practice

Annette An-Jen Liu

Ruth Ju-shih Li with her work during a public demonstration at Yingge Museum, overlooking a backdrop of Taipei City. December 2019. Photo: Tzu Chun Fan

I have always been confident in my identity as a Taiwanese woman, despite only having lived in Taipei for six years. My sense of belonging and nationhood to Taiwan is perhaps strengthened by the fact that the country’s sovereignty continues to be contested and undermined in ongoing political tension with mainland China. To be Taiwanese is to almost share a fragile pride, one where defensive public sentiment is easily triggered when the question of sovereignty arises, whether it be threatened or made non-existent due to complex, international political pressures.

Existing within a complicated geopolitical context due to its unique history, there is a persistent attempt by both the government and its citizens to constantly reaffirm Taiwan’s independence as a nation. There were many defining moments in 2020 that resulted in actions that strengthened Taiwan’s national narrative. These included the President Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文) re-election; Taiwan’s successful management of the COVID-19 outbreak; the #TaiwanCanHelp and #TaiwanIsHelping campaign that saw over 50 million masks donated to more than 80 countries in 2020; and the Taiwan parliament’s renaming of the national carrier from China Airlines to Taiwan Airlines to avoid being mistaken for a mainland China airline. There was also the significant passing of the first Taiwanese-born president ‘Mr. Democracy’ Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), which marked the end of an era that symbolised Taiwan's transition from a colonial and authoritarian rule to a vibrant democracy; as well as the October 2020 cover redesign of Taiwan’s passport emphasising ‘TAIWAN’ in bold text, while downsizing the island’s official name, the Republic of China.1

These defining moments were, and continue to be used, framed and discussed in a way that propels the country’s evolving identity as a proudly democratic nation — one that is historically and culturally distinct from its counterparts in the region, and most importantly, from mainland China. As I observe these efforts, I reflect upon the concept of nationhood, particularly for Taiwan, as one that requires relentless work and activity — a process that attempts to gain further international recognition and acknowledgment in order to reinforce its self-definition.

Fresh produce markets, Taipei, Taiwan. January 2021. Photo: Yun Tong Lin

Art institutions, specifically in the form of national museums, play a significant ongoing role in framing and negotiating these national narratives. Direct examples of this are: The National Palace Museum (國立故宮博物院) in Taipei, which was constructed in 1965 by the Kuomintang (KMT) (國民黨) Chinese Nationalist Party, following the Chinese Civil War; and the museum’s Southern Branch extension in Chiayi, which is a government proposal in 2000 by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (民進黨), the dominant opposition party.

The National Palace Museum’s collection has a profound history of imperial items amassed over centuries of dynastic rule in China. With the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911, they entered the public domain and symbolised both the end of monarchy and the KMT’s succession to political authority. 2 As the National Palace Museum was set up to house the collection, the institution soon became an ideological instrument for the KMT to develop and promote a strong Chinese nationalism on the island of Taiwan through the museum’s grand Chinese-style architecture and displays that highlighted KMT’s ‘heroic efforts’. 3

Recognising the rich cultural authority that the palace collection has, the DPP worked to distance it from the grand Chinese national narrative and sought to assert Taiwan as a subject in its own right. A proposal by the DPP to establish the National Palace Museum Southern Branch (國立故宮博物院南部院區) was a gesture to reposition the museum in a new context of Asian cultural heritage, one where Taiwan could stand autonomously. Not only did this echo a rising Taiwanese subjectivity, but there was also a desire to promote cultural exchanges between Taiwan and other countries in a globalised 21st century, through the reorientation and extension of the National Palace Museum. This goal and strategy of cultural diplomacy highlights a transformation of museums in Taiwan where institutions are deployed to ‘[increase] Taiwan’s exposure on the world stage’ in a context where the country’s sovereignty continues to be contested and threatened.4

The New Taipei City Yingge Ceramics Museum (新北市立鶯歌陶瓷博物館), which opened in 2000, is an example of these efforts to culturally frame and promote Taiwan on both a local level and within a global context. Located in the Yingge District, the museum aims to develop local tourism and revitalise the rich ceramic industry in the area that they suggest had existed for over 200 years since the arrival of the first potter Wu An (吳鞍) from Guangzhou, mainland China. 5

The museum is overseen by the local government’s Cultural Affairs Department and was a project that followed the renovation of the Old Street in 1990, a pedestrian area that preserved heritage buildings, kilns and saw major economic redevelopment of spaces for largely tourist ceramic stores and DIY workshops. On the Yingge Museum website, Director Wu Hsiu-Tzu (吳秀慈) stated that, as a government institution, the museum is not only “dedicated to the research, curation, preservation, and maintenance of Taiwan’s ceramics culture and art” through exhibition and education programs that engage with local communities, but it is also responsible for “elevating Taiwan’s ceramics industry and ceramic art to the global arena,” as stated by the Director Wu Hsiu-Tzu (吳秀慈). 6

This commitment to place Taiwan within the international ceramic world was exemplified when the museum took over the organising of the Taiwan Ceramics Biennale from Taipei’s National Museum of History (國立歷史博物館) in 2004. This move opened up its application to international artists by inviting judges from outside of Taiwan. In its eighth edition, the 2020 biennial boasted 732 entries from 58 countries with a diverse judging panel of individuals from the UK, France, Japan, Indonesia and Taiwan. In 2009, the museum launched its Residency Program, inviting around ten artists each year (at least two would be Taiwanese) to spend three months at Yingge where they would be required to host workshops for local schools, give artist talks, and donate one piece of work to the museum’s growing collection. As a member of the International Council of Museums, the Yingge museum also hosted the general assembly of the International Academy of Ceramics in 2018, an international conference that recognised and boosted the museum’s status globally.

The Yingge Ceramics Museum is an influential cultural platform that is actively trying to place itself on the world map as a museum from and of Taiwan. However, the municipal government’s effort that seeks to emphasise Yingge as a ceramic capital seems to be only engaged by the institution. While the museum and the Old Street are connected by a footbridge, they feel incredibly disjointed. When I visited Yingge in November 2020, I was shocked by the surplus of souvenir stores on Old Street that sold the same, mass produced, cheap ceramics and tea sets. It was obvious that in an attempt to promote cultural tourism, the area had become commercialised and irregulated, with little to no sight of contemporary ceramics and artistic production outside the exhibitions of the museum.

Ruth Ju-shih Li with her work during a public demonstration at Yingge Ceramics Museum. December 2019. Photo: Tzu Chun Fan

For this essay, I spoke to Taiwanese-Australian ceramic artist Ruth Ju-Shih Li (李如詩) via video chat in December 2020 about her experience at Yingge, where she was a 2019 resident artist at the museum.7 As a ceramic artist who works between Australia, China and Taiwan, Li "explores different ways of narrating both traditional and multicultural concepts of beauty, transcendence and the sublime. She draws from her diverse philosophical and cultural heritage, and from the language of dreams, myths and utopias."8

Speaking with me, she shared the same sentiment about Yingge: viewing the museum as completely separate from the Old Street, and noting that the commercialisation was very similar to Jingdezhen, the historic city in China famous for its porcelain and fine ware production, where one of Li’s studios is based. She also expressed that while the museum seemed to operate independently from the rest of Yingge—acting as more of a "government-run community-focused institution" with a focus on local public outreach—she felt that the museum was promising and had "definitely brought Taiwan onto the international contemporary [ceramics] world map" with its residency program.

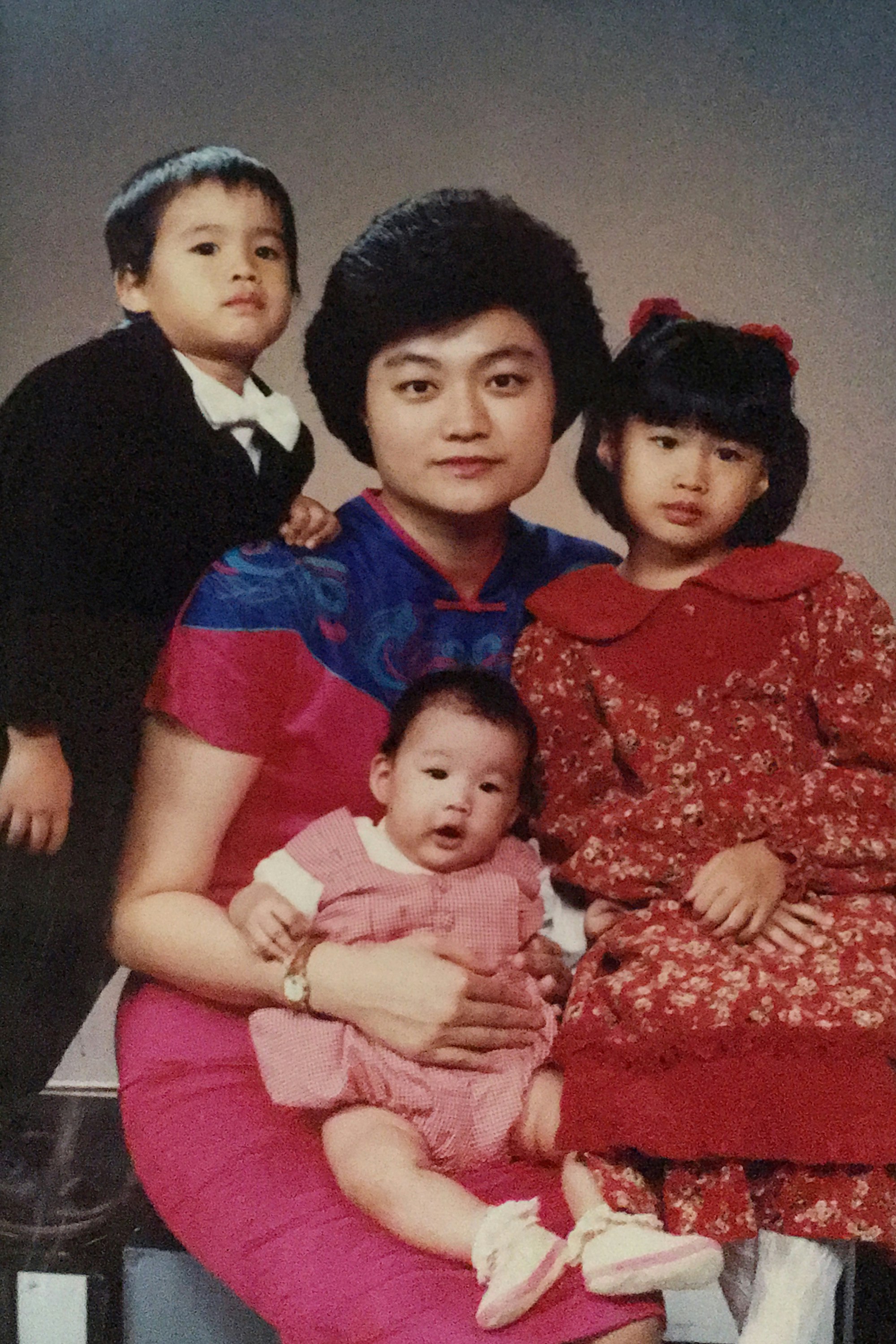

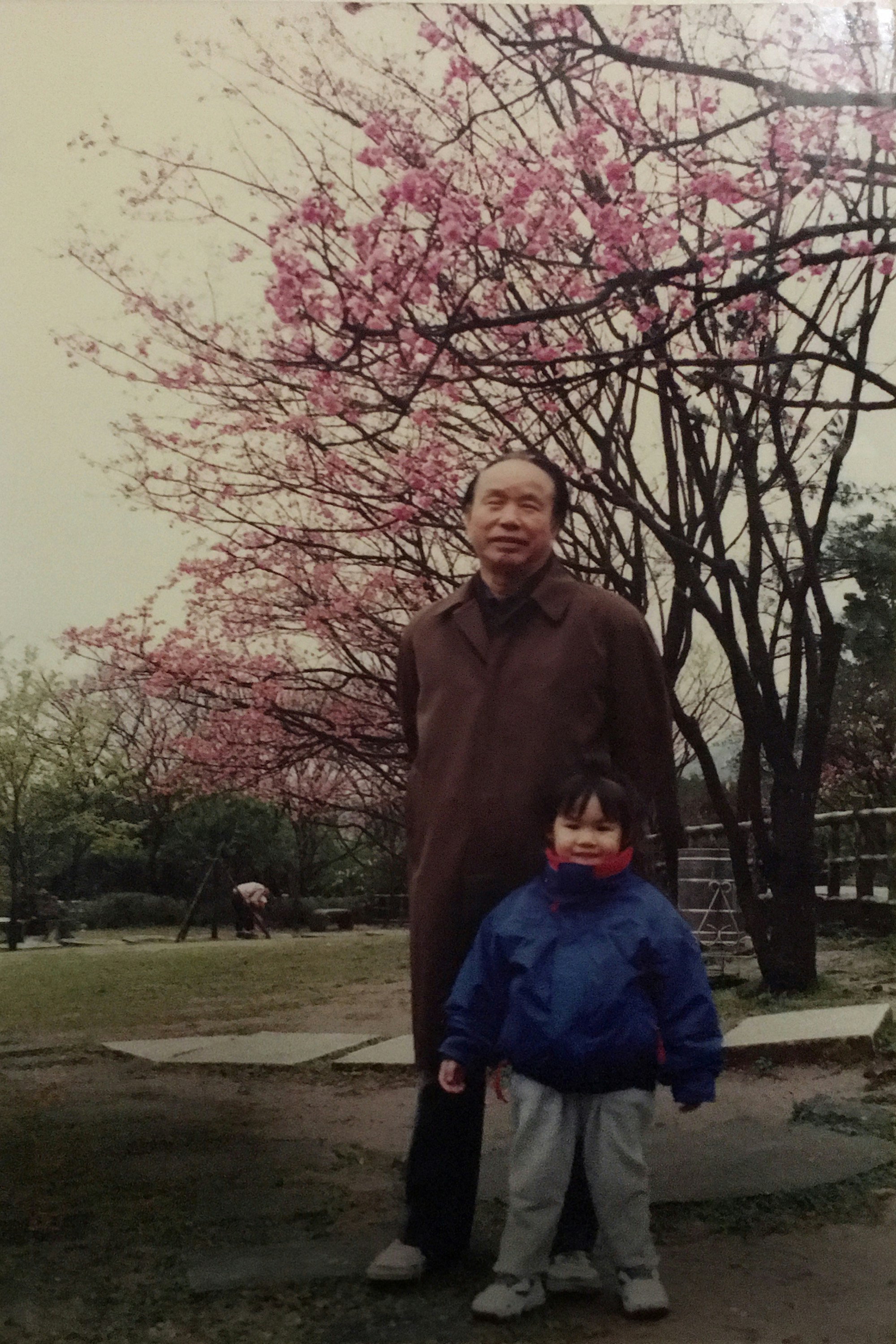

Ruth Ju-shih Li with her siblings during her childhood. Courtesy the artist.

Having immigrated from Taiwan to New Zealand and then Australia at the age of 3, Li first heard about Yingge from her ceramic teacher at the National Art School in Sydney (where she graduated in 2013). During this time, the Head of Sculpture found out Li was Taiwanese and encouraged her to consider applying to the Yingge Museum residency program, because she saw it as being prestigious, competitive and highly-regarded. “The residency is really famous in the ceramic world because it is so well-funded,” Li explained to me, “and I think that’s really, really important because it’s what keeps it competitive, so we know that the artists [who apply] are of a certain quality.” She added that the Yingge program sits alongside the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park Artist Residence Program in Japan and the Clayarch Gimhae Museum Residency in Korea as prestigious programs in Asia. “I think it’s very important [to put] Taiwan on the forefront of culture and art, and [this] is really the strategy to go for” Li further reflected, echoing the importance of the cultural diplomacy approach that Taiwan must employ to define itself.

Despite the heavy commercialisation of the Yingge district, Li also emphasised that the residency program, based out of a museum with exhibition opportunities, plays a critical role in supporting contemporary ceramic practices that often do engage with Taiwan as part of a contemporary art dialogue. “Three months is quite a good chunk of time,” she added, “as it allows artists the time and space to do a new project or research where [they] have the freedom to try new things, new materials, and work with the local community there. I think it’s great. Li used her residency to delve into her autobiographical practice, as it was the first time she could spend such an extended period of time in Taiwan.

Li has made the pristine white Jingdezhen porcelain her signature material, using it to create incredibly delicate forms of flora and fauna to reflect on the fragile paradox of life and death – a theme that stems from deeply personal experiences of loss. She has drawn inspiration from the Biblical story of the Garden of Eden, creating an intricate body of work with disembodied wings as a recurring motif, where she considers the transitory nature of the human condition.

For her 2019-2020 exhibition Florilegium at MAY SPACE in Sydney, and then at Yingge Museum, where she showcased a larger body of work, Li created two ephemeral pieces onsite, using clay to build a sculptural bouquet that rested on top of a traditional Chinese wooden plant stand. With water bags installed above them, the sculpture gradually eroded as water dripped onto the unfired clay, a performative installation that explored the impermanence of life. Also titled Florilegium, this piece was awarded the Special Prize in the 2020 Taiwan Ceramic Biennial.

During her residency, Li began to examine her early memories of Taiwan. Even though they were vague, the abstract memories that she did hold consisted of distinct colours, smells and tastes. Reflecting on the portion of her childhood spent in Taiwan, Li described: “Taipei is really colourful. There are specific colours that you would just recognise anywhere and wouldn’t confuse it for a street in Hong Kong or Japan…from the sun-faded red spring couplets [on] my grandfather’s doors to the really cheap plastic mint chairs from the night markets in Taipei, when you scoop goldfish, to the blues, yellows and reds on the temples – these were the starting points of my research.”

Nostalgically revisiting and photographing significant locations of her childhood, Li began an image archive that prompted her to work with colour for the first time. “My previous work was just pure porcelain, so I wanted to incorporate colour because my work is autobiographical in nature,” Li noted. “I wanted to have that element of memory [highlighted] onto the sculptures.” The images she took served as visual reference, with the colours becoming ‘memory triggers’ that slowly got abstracted as Li introduced them into her work.

The research Li began at Yingge with experimentations into colour culminated in her exhibition Inflorescence (2020) at MAY SPACE. Expanding on her meticulous visual vocabulary, the exhibition presented a series of floral, organic porcelain forms in mostly white and black, where each of them are “interrupted” with a burst of colour, “reminiscent of an unexpected memory intruding on the everyday.”

For this exhibition, Li also worked with Australian black clay for the first time, an exploration that was borne out of not being able to access her studio in Jingdezhen due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. She grew to love this type of clay for its uniquely intense colour, quickly integrating it into this new body of work that reflected on place and memory — a culmination that is also representative of her Taiwanese-Australian identity.

When I asked Li how she saw her dual nationality in relation to her practice, she told me: “I think every Asian-Australian or migrant-Australian would struggle with identity, and especially [as] artists, we kind of all explore this, either on purpose or subconsciously.” While she doesn’t actively or directly explore her identity as a Taiwanese-Australian, there are elements in her work that hint at her heritage, such as the traditional Chinese wooden plant stands in Florilegium.” Because my work is autobiographical, it is a self-portrait, so it came naturally to me to use [such] elements,” she explained.

Dusk and Dawn, 2021. Photo courtesy of Ruth Ju-shih Li and MAY SPACE

I return to reflect on the frameworks that define national identities and those that construct a sense of nationhood. On the macro level, there are national institutions like the Yingge Ceramics Museum that utilise their platform in cultural diplomacy as a way to frame Taiwan’s identity and locate it in a global context. However, this soft power work of the museum through external engagement is completely distinct — even dislocated —from the cultural production of the Old Street. With artist commissions and displays of contemporary ceramics, the Yingge Museum is a space that facilitates and encourages innovation and creativity beyond the local, while the Old Street perpetuates commercial, generic production of clay manufacturing for mostly unchanged, domestic tourism. Similarly, Ruth’s practice evokes a sense of Taiwanese national identity that is contemporary and engaged; one that is informed by her birthplace of Taiwan, but is also constantly evolving with various lived experiences .

Her practice, as subtle explorations of the self, is inherently autobiographical, framed within memory, experience, and place. My exchanges with Ruth were a reminder of the extent to which all artistic and curatorial practices are defined through our personal narratives and impacted by institutions and their unique, attached nationalism.

Editor's Note: Annette An-Jen Liu participated in the Curatorial Assistant Program mentorship (2020-2021) at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, where she served as the Assistant Curator for the Drawn by stones group exhibition, mentored by Project Curator Bridie Moran. Annette's contribution to 4A Papers forms part of her mentorship, and is supported by the Cultural Division, Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Sydney.

Ruth Ju-Shih Li was featured in Drawn by stones and has previously exhibited in China, Korea, Sydney, Taiwan, and Thailand. She is represented by May Space, Sydney. Drawn by stones was presented by 4A and Counihan Gallery, Melbourne from 31 July–12 September 2021. Click here for info on Drawn by stones.

Notes

- These defining moments were current as of January 2021. The background to these milestones include: The argument to rename the airline regained momentum happened when a series of China Airlines' cargo flights were used to deliver COVID-19 medical supplies around the world–an effort many were fearful would be mistakenly thought to be from mainland China. As of July 23, 2020, this petition had over 50,000 signatures. Source: Wong, Maggie. "Taiwan's parliament approves proposal to rename China Airlines." CNN, 23 July 2020. Accessed September 2021. The passing of Lee Teng-hui marked the end of an era that symbolised Taiwan's transition from a colonial and authoritarian rule to a vibrant democracy. While Lee was a complicated and often controversial figure, his passing was ultimately mourned and reported with grace and gratitude for championing Taiwan's independence–an ongoing effort that frames much of Taiwan's political and social discourses. Source: "Lee Teng-hui, 97, Who Led Taiwan’s Turn to Democracy, Dies." New York Times, 30 July 2020, Accessed September 2021.

- A decade of military upheavals began after the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911; first with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, followed by the Chinese Civil War in 1945 with the rise of the Communist Party. With each disruption, the collection was relocated and dispersed multiple times across different cities for safeguarding. The possession of the national treasures and the commitment to protect them represented the KMT rule as legitimate; as the rightful successors of China following the last dynasty.

- The DPP’s 2000 Presidential election ended 55 years of continuous KMT rule, a symbolic victory that saw the new government promoting Taiwan as an independent sovereign state from mainland China. Source: Following the election, the DPP appointed a new director, Tu Cheng-sheng (杜正勝), to the National Palace Museum, who repositioned the institution's narrative with a Taiwanese perspective, producing exhibitions that focused on Taiwan’s early colonial histories, its connections with European countries, and relations with neighbouring Asian nations other than China. Furthermore, in a 2004 renovation, statues of both Sun Yat-sen (孫中山) (first leader of the KMT) and Chiang Kai-shek were removed, further distancing the museum from its KMT association. Source: Y-C. Huang, ‘National Glory and Traumatism: National/cultural identity construction of National Palace Museum in Taiwan,’ in National Identities, New York: Routledge, 211-225, 2012, DOI: 10.1080/14608944.2012.702742

- Momphard, David. "Yingge ceramics turn 200." Taipei Times, 15 October 2004,

- "Director's Welcome." Yingge Ceramics Museum, 25 December, 2020, Accessed September 2021.

- "Director's Welcome." Yingge Ceramics Museum, Ibid.

- Unless otherwise acknowledged, all quotes by the artist are excerpted from an interview between the author and the artist, December 2020.

- Sourced from Ruth Ju-Shih Li's biography, supplied.

About the contributor

Annette An-Jen Liu is a Taiwanese writer and curator working between Australia, Taiwan and New York City.