Banoo’s Comb

Kirtika Kain

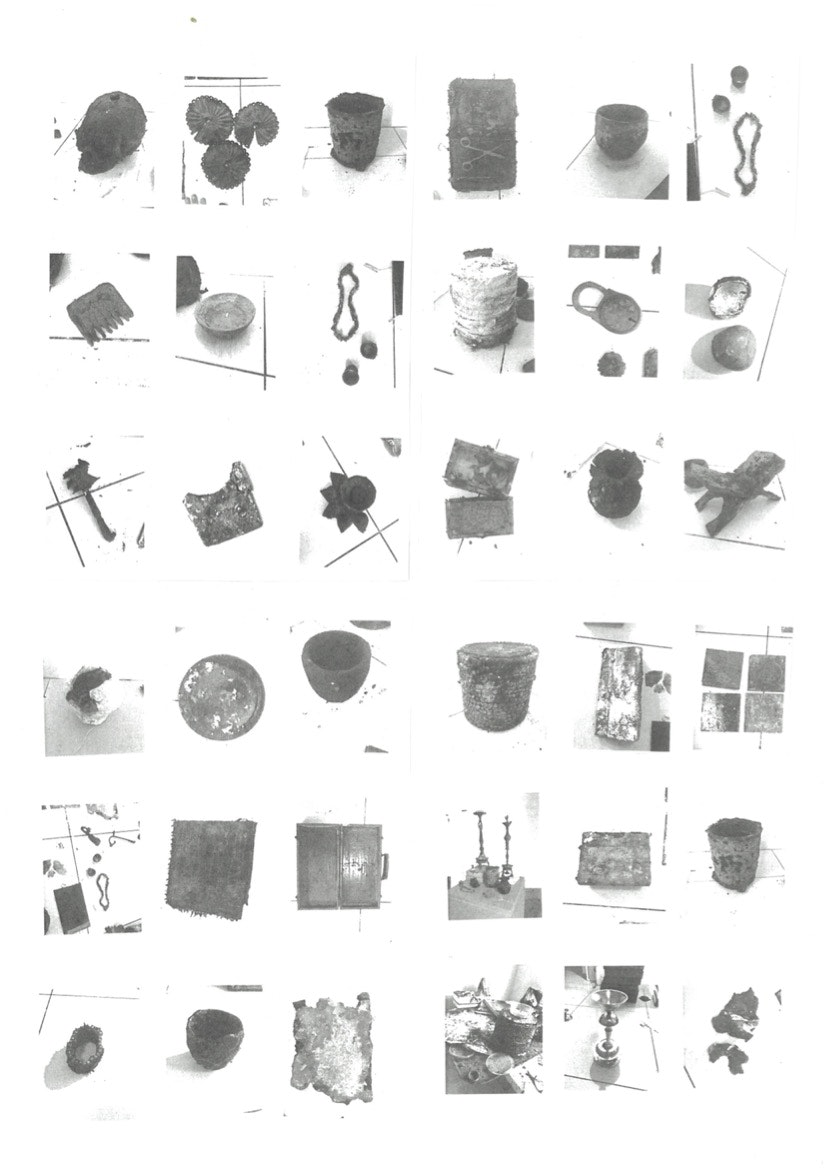

Earlier this year, I collaborated on Earth 200 CE, an exhibition at Sydney’s Verge Gallery that attempted to envision a Dalit cultural museum. To realise this, I transformed the gallery into a fictional archive of objects inspired by the short stories of writer Baburao Bagul. I chose to respond to Bagul’s seminal 1963 collection When I Hid my Caste, as I could visualise the objects I wished to create through his vivid writing. Bagul’s words animate everything with life; every object has a persona and a presence. I created small sculptures of ritual objects, musical instruments, trinkets from the dressing room, items from kitchen—as if I had shaken his literary world and all these things had fallen out. A pioneer of Marathi and Dalit literature, Bagul has written characters who live the cruelty of the inhumane Indian caste system, much as he did. There is one character from his short story 'Prisoner of Darkness' who I find to be an enigma. I have not stopped thinking about her.

Her name is Banoo. She is an Untouchable and one of the most compelling characters of Indian literature. She is the widow of Ramrao Deshmukh, a prominent village chief who is lying on a funeral pyre in the opening scene. His son Devram is in deep rage, thirsty to avenge his father’s death by murdering his stepmother. He gathers stones and with the force of a mob tailing him, he hunts Banoo down. Through Bagul’s words, it feels as though the pages are writhing and the earth is trembling with the fury of this man—even the pebbles underfoot scramble to avoid the force of his might.

Who is this woman? Who is this force that dredges up such mania and vitriol from the mob? How excitable they are as they follow Devram to Banoo’s home. They call for her to be senselessly raped, to be stripped naked, paraded through the village, tied up, publicly whipped and her body to be burned on the pyre. Even the police officer joins in the chants, calling her a whore, among casteist slurs. When Devram finds her, he is seized by her beauty and is not sure whether to kill her or make love to her. He nonetheless torments her and she escapes her home for the first time in twenty years.

The awaiting crowd is stunned to behold her. The men lust over her with lewd demands yet fear they will be emasculated by her black magic; the women hide their children. The villagers are safe to hurl insults only because they are banded together. We come to learn that as a child Banoo was dedicated to the temple as a murali by her poor father, the plight of many young Dalit girls. A murali is a girl child offered to the temple by a family who are unable to provide for her. Although the family believes this is her divine call, it often leads to sexual exploitation and a path to prostitution. Multiple men, driven mad by her beauty, would come to see Banoo and intrigued by these accounts, Ramrao had offered money in exchange for her.

We learn that she had birthed a son, Daulat, who grew to see his mother through the eyes of the village—as a sinner. Despite his disgust and humiliation, Daulat comes to his mother’s aide. As Banoo is being chastised publicly by Devram, the young Daulat stabs his stepbrother in the back and the story concludes with the mob thrashing Daulat and Banoo drenched in shame and blood, her clothes tattered and her hair across her shoulders.

I have read this story over and over again. For the exhibition I created Banoo’s comb as I imagined it to be. I envisaged her tresses to be wild and untameable, like her sensuality. I was left with so many questions from this tale: What is this societal urge to destroy the Dalit woman? To debase and defile her?

And most significantly, what is this power that she holds that terrifies them all? What if she were to yield it or grasp its potency?

And most significantly, what is this power that she holds that terrifies them all? What if she were to yield it or grasp its potency?

What if she were not the subject of such a demeaning system, if she expressed herself fully without threats from a volatile patriarchal society? What does her laughter and song sound like? What of her dance? What are Banoo’s desires? I think about Daulat. How can a Dalit child not be maddened by the stigma of caste?

Bagul’s writing is more poignant today than ever. Although fictional, his characters are not mirages, they point to the living, heaving reality of a barbaric system. They are neither heroes nor powerless victims, they are beguiling and embody the fullness of Dalit experience— maternal love, devotion, defiance, grief, sensuality, anguish and passion. He does not censor the cruelty of a society that dehumanises the existence of a Dalit. In light of appalling and increasing rates of sexual crime against Dalit women, these stories remind us of the prejudices and stigma within which the Dalit body is held. There is no neat answer in Bagul’s world, there is only an entry point to understand a wound that is ancient yet more pressing than ever.

Notes

Image caption

Earth 200 CE artefact collection, Kirtika Kain, found and treated objects, 2022, dimensions variable; courtesy the artist.

A note on the artwork

This is a xerox catalogue of items displayed in the exhibition Earth 200 CE. The items were photographed individually and collaged prior to being edited and scanned for this editorial - Kirtika Kain.

About the contributor

Kirtika Kain is an artist on Darug Country in NSW, Australia.